Hello again folks! Now we get to the fun stuff…the ideas I’m currently playing with as to how and why these five torcs (or torc group in the case of Alrewas) might have been deposited where they were.

As I see it, there’s three main options…and an equally likely, or perhaps even more likely, fourth: ‘bits of any or all of the above’. The three main options are: Iron Age deposition, deposition in the Roman period and – yes, you guessed it – the blooming Vikings again! The reasons for and against are:

Iron Age deposition

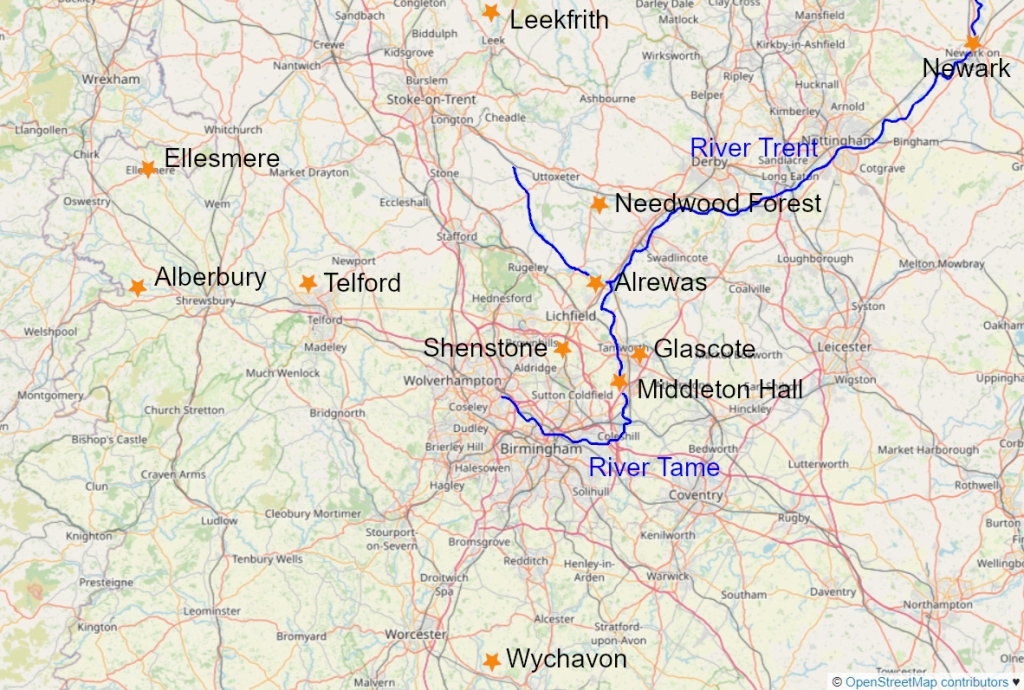

These are Iron Age torcs so the obvious time period of, and reasons for, their deposition should be found in the Iron Age. That they were found as single torcs might count against this: generally Iron Age torcs are found in small groups of 3-4 torcs (for example, Leekfrith, Netherurd, Ulceby, Clevedon and Blair Drummond). Complete torcs are almost never found alone, unless there has been potentially some kind of interference with an earlier deposit (yes, I’m looking at you, Vikings, but more of that later…). There is also the idea of torcs being buried on higher ground or on slopes, but this does not apply to any of the Staffs Five, most of which appear to have been deposited close to rivers or streams.

As such, I’m starting to think more about the different ways torcs have been deposited in other – securely Iron Age – places to see if there’s any comparisons: at Snettisham in East Anglia, there seems to be a differentiation between complete or substantial pieces of torcs, and smaller, cut or broken, fragments. At the Snettisham site, complete, or near complete, torcs are generally buried together in discrete hoards. Smaller cut and/or broken pieces are mostly buried in separate deposits alongside ingots, coins and other material which could be seen as scrap, or metalworking materials, rather than objects.

This is a pattern across Britain more widely, where it is rare to have hoards of broken torc material in the Iron Age, the exception being where dismembered but still potentially ‘useable-in-something-else’ torc pieces, rather than cut scraps, are included. Examples of this would be the disassembled terminal and neck ring from the Clevedon torc deposit in Somerset, the detached terminal included in the hoard from Netherurd, Peeblesshire and the half of a lobed torc from the Blair Drummond hoard, found near Stirling. This could have implications for the Staffs Five, where we have two incomplete torcs, two complete ones and a secured bundle of apparently ‘adapted’ torcs from Alrewas. It started me thinking: in the Iron Age, do we have different deposition rules for different types of torc depending on whether they were complete or broken/cut up? Did this change over time? Do torc deposits relate to rivers and/or roads and intersections? Were intersections and crossing points important, as they were at later dates?

In a comment on the last blog, Peter Reavill – an archaeologist with a lot of knowledge about this western area of Britain – got me thinking by suggesting that, in the west, intentionally cut small torc pieces and other significant small finds, such as ingots, are largely found in liminal areas, that is, areas on the edge of society. It’s certainly something to consider, although I’m still not sure. There is, after all, a scatter of intentionally cut small torc finds from all manner of different places right across ‘England’. Often small and easily misplaced, it is equally possible that they are unintentional losses. However, getting into the mindset of prehistoric ritual is not a task I find easy, although I am sure, as with all ritual, that it was there, perhaps often tantalisingly just beyond my mental grasp.

So yes, if we are thinking Iron Age, then these are very much not typical deposition sites. But perhaps it’s time to rewrite these theories? Perhaps these are typical, but we just haven’t had enough data, or looked closely enough, to identify the patterns before?

Deposition in the time of the Romans

I’ve been very careful how I word this, because the depositions could have been made by Iron Age people, but in Roman times. Alternatively, it could be deposits of Iron Age material, by people who thought of themselves as Roman.

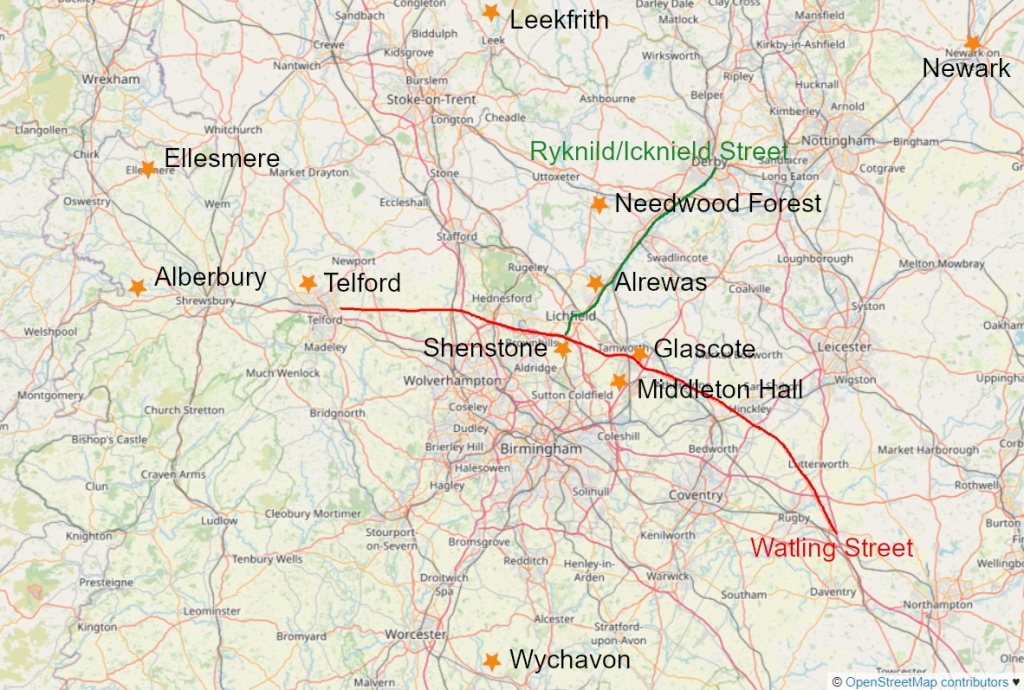

So why has this thought of Romans crossed my mind? Time for another map:

As you can see from the map above, there are two major Roman roads which intersect in the vicinity of the finds: Watling Street and Ryknild/Icknield Street. When I originally saw the torc locations, my mind immediately slipped to Boudica and the supposed final battle of Watling Street in AD 61. This battle has often been assumed to be at Mancetter, a location less than a couple of kilometres to the east of the torc scatter.

Icknield, a name long associated with the Iceni, piqued my interest. However, a rough-and-ready Google search, suggests that the name of Ryknild Street is actually 12th century and that the alternative name of ‘Icknield’ might be an unrelated corruption. However, this is by no means certain as this road, like the Icknield Way, certainly heads east’ish towards Iceni land, at least in its earlier part. Worth investigating a bit more, I think.

The torc deposits are so tempting to link to the revolts – is it possible we’ve found the site of Boudica’s last stand, closer to Tamworth? Is the battle site identified by several torc deposits given as offerings, or perhaps the torcs were buried as war booty? This isn’t as crazy as it first sounds: it is thought that the Boudican army deposited a bronze head from a statue of Nero, and a piece of horse sculpture enroute from Colchester back to Icenian territory. My mind was racing with all kinds of wonderful theories. But, then I read Duncan Mackay’s Echolands book, and this blew my career-making ‘Boudica battle location’ idea clean out the water! *Sob*

In his book, Duncan compellingly argues that Boudica had never got beyond the vicinity of Verulamium, and was defeated just outside the town. His proposed battle site, fitting both the historical accounts and – more importantly – also the archaeological evidence, means my Tamworth battle(ship) is well and truly sunk!

However, I still think the proximity of the torc finds to the Roman roads might be a clue, and of course, it is highly likely that the Roman roads in the area had earlier, Iron Age, incarnations which were just further developed by the Romans. As such both Iron Age and Roman dates (and indeed later, see below) could be supported by a proximity to roads, and indeed rivers (another form of Iron Age and Roman highway).

The other thing to bear in mind as we try to work through the range of possibilities, is that the torcs could still relate to the Icenian-led revolts of AD 47 and AD 60/61, even though not to the main battle – they could be local offerings made before, or as deposits made during/after the time of war. It is not unlikely that there were local, albeit historically unrecorded, skirmishes between the Roman army and locals at various points during both major revolts. It is also likely that the revolts were not as isolated as has been previously assumed. However, it’s impossible to tell at present, so I’ll leave it there.

The final theory of deposition date is my recent research nemesis – the Vikings!

The Viking Great Army

When I first saw this collection of torcs, I was working on our previous paper on the possible Viking ring from Knaresborough and a related stolen Iron Age hoard found in north eastern Britain. At the time, I checked through every torc photo and record I had and could not find anything, such as ‘nicks’, about the Staffs Five which raised alarm bells and so I discounted the Staffs Five as being related to Viking stolen hoards. However, since then, and in particular after looking for parallels for the way the Alrewas torcs were assembled – and at the locations of all the findspots – I have not been able to rule this one out. Time for another map:

Newark is the southernmost torc find of our previously identified Viking re-deposited finds, and what have we got just south-west of it? Two Viking camps or sites of Viking Great Army activity: Repton and Catton. It kind of speaks for itself really.

[As an aside, I highly recommend getting hold of a copy of Dawn Hadley & Julian Richards’ book ‘The Viking Great Army and the Making of England’, it’s a great read!].

Therefore, close to the Catton and Repton sites and in the vicinity of several river crossings and major roads (the Vikings are known to have used Roman roads, as well as the river network and deposited finds at crossings and important travel intersections) we have the Staffs Five. In particular the Alrewas torcs look suspiciously Viking ‘adapted’ and were found only a few hundred metres from Catton. When I showed the Alrewas torcs to Trix Randerson – a Viking specialist who we wrote the Knaresborough paper with – he immediately shared with me a photo of a silver ‘bundle’ from the Viking Silverdale hoard from Lancashire. You can see where he was going with this. I think we have to include the Vikings as a possibility.

Will I never escape the blooming Vikings!??

And finally…

The final possibility, the ‘a bit of any or all of the above’ theory seems just as likely: as we’ve seen, Alrewas looks very much like the Vikings have been playing with Iron Age torcs, but both Glascote and Needwood Forest could be Iron Age, time of the Romans, or indeed Viking (the probable Viking deposited Newark was found singly, by a river). Middleton Hall again fits the profile for any of the above. However, the Shenstone torc feels less related to the rest, perhaps because it is not gold, but made of copper alloy, and also because it is broken/cut, rather than being useably-disassembled. However it is equally possible that it is older than the other torcs, and perhaps therefore had a value that transcended it’s condition or material? Or perhaps like the similarly cut and deposited, albeit gold, Caistor torc, it was also a Viking plaything? We can’t entirely rule out its deposition relationship to the others.

From the above, we may not actually be looking at a distinct collection of torcs at all, but a series of different events that created an artificial cluster. The only place left to go with this is to look at the torcs themselves, to see if they offer any clues and then weigh up the balance of probability that will come from a greater, more in-depth, examination of everything I’ve written in these blogs so far.

We shall see…

In the next blog, I’ll be talking about what looking at torcs actually entails, and the data I record when looking at torcs. Until then, it’s always good to torc, so do get in touch, leave a comment…and don’t forget to click ‘Subscribe’ below.