by Tess Machling

[A download/print PDF version can be found at the end of the paper]

This paper can be cited as: DOI 10.5281/zenodo.14193776

Introduction

A few months ago, I received an email from Andrew Fitzpatrick, a fellow Iron Age specialist, regarding something he had seen in Christopher Tripp’s book, Thurrock’s Deeper Past: a confluence of time (Tripp 2018, 108). The book mentioned a torc, found in West Tilbury, Essex, in 2000, which had apparently disappeared from the public gaze. Tripp’s account was based on an earlier, more detailed, article by the late Randal Bingley, then curator of Thurrock Museum, which was written for the 2015 issue of the Thurrock Local History Society’s publication Panorama (Bingley 2015, 70).

Tripp’s and Bingley’s accounts of a ploughed up torc, now sold or hidden – and the various rumours surrounding it – had piqued Andrew’s interest. As neither of us had heard of the torc before, I offered to carry out some more research so that – if nothing else – there was a record of it in the public domain, on The Big Book of Torcs. This article is the result of that research.

A rumoured torc.

In 2004, in a note in Panorama (Bingley 2004, 47), the following appeal was made,

“A rumour has been widespread in Essex for nearly two years, apropos of a major archaeological discovery from West Tilbury in or about the spring of 2000. The item concerned, allegedly found by chance during agricultural land work, is said to have been a gold twisted wire Celtic torque of more than two pounds in weight.

No such object has been declared under the Treasure Act during the intervening period. If anyone can add even the slightest additional data to the above, or can either confirm or refute this rumour’s authenticity, will they please inform any of the Society’s Officers or committee, or contact the Thurrock Museum staff.”

By 2015, further information had come to light and Bingley wrote a detailed account of the torc and attempted to disentangle the various rumours and accounts that the informants had given him over the years (Bingley 2015).

Bingley’s account

Bingley’s account begins with a note made by him in December 2004:

“My West Tilbury agent informs that about 2-3 weeks ago, a contact said that the person in Cambridge supposed to have present illegal possession of the golden torc…is about to dispose of it by auction. Nothing is known whether one of the major art-auctioneers is involved, but the disposer is said now to have obtained some sort of legal title to it – whether that means faked provenance has been prepared, I do not know. The price is anticipated to reach a million and a quarter or more sterling” (Bingley 2015, 70)

He then goes onto detail a rather complicated tale. The torc first came to the attention of the heritage world on 10th July 2000, when Jon Catton (Heritage and Museum officer for Thurrock) overheard a conversation in Atticus books in Grays, Essex. The conversation took place between the bookshop owner and a customer, who was enquiring about old OS maps of West Tilbury.

The conversation detailed how, in earlier 2000, a torc had been found by a farm worker; that the torc was 1020g in weight; that a photograph of the torc had been taken at its find spot, which showed it to be in West Tilbury and that the torc had not been declared and that arrangements were being made for its sale to an American buyer.

Bingley then set about trying to find the find location, with a programme of fieldwalking to look for recent digging disturbance, etc. No such evidence was found, but over the following years Bingley collated a number of accounts of the torc and its whereabouts. The farm worker who had discovered the torc and the detectorist who had helped clean it were found and a find spot probably in an area to the north-east of St James church was identified. There were further additional details including an armed hold-up carried out against the cleaner in an attempt to steal the torc (this was unsuccessful, as the cleaner had managed to convince his assailants that the torc was no longer in his possession).

The finder having attempted to sell the torc to a buyer in London – who backed out ‘considering the torc to be too dangerous to handle’ (Bingley 2015, 72) – then apparently sold it for c.£30,000 to a Cambridge ‘collector’, a medical professional who – rather alarmingly – ‘already possessed a number of other gold torcs derived from clandestine sources’ (Bingley 2015, 73). [I cried when I read this, I really did!].

During the progress of the torc from field to collector, a number of photos had been taken, although many of these were later destroyed ‘for fear of police investigation’ (Bingley 2015, 73) leaving only the two shown in Figs. 1 & 2, which were given to Bingley.

In October 2001, the landowner was informed of the find and the finder was interrogated, although no prosecution was brought. Also in late 2001, information was given that the torc had been advertised for sale online – as ‘The West Tilbury Torque’ – for the sum of £400,000. No evidence or trace of such an online post could be found. In January 2005, a file of notes and the two photos was given to the British Museum.

Further details

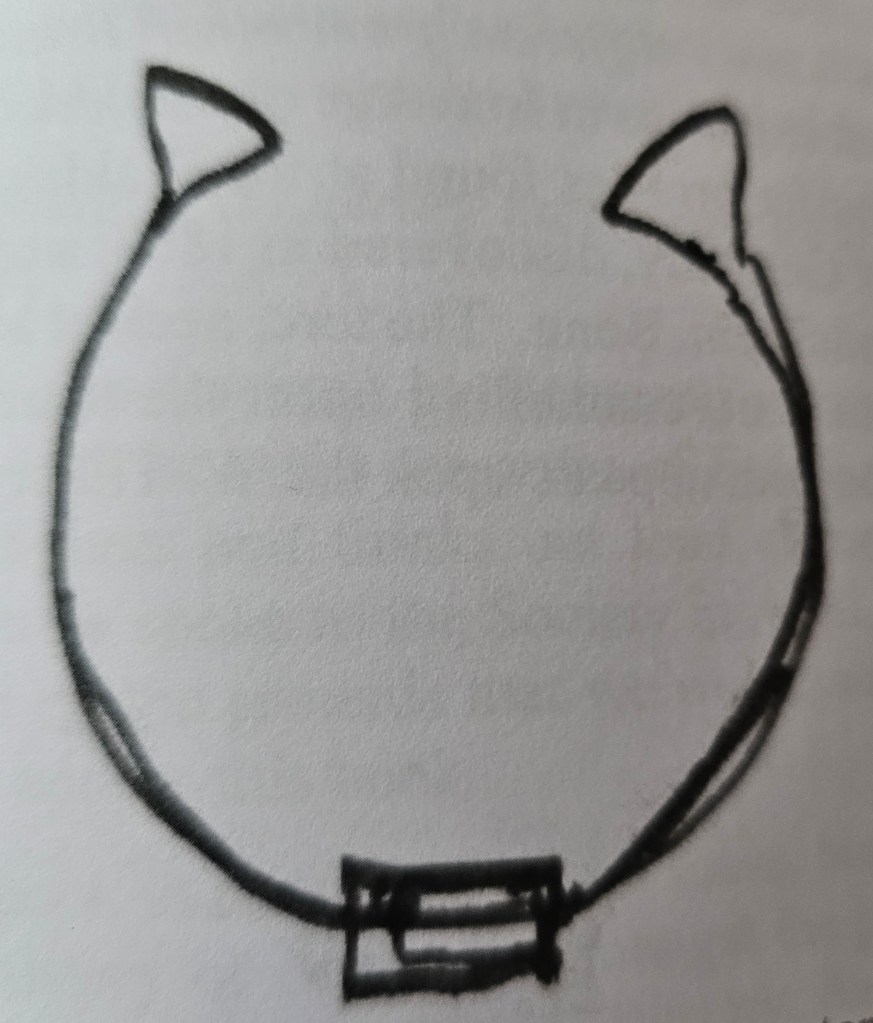

The torc was described by Bingley as having been approximately 20.5cm in diameter – a standard torc size – and weighed 1020g. It apparently comprised a neck ring of three twisted coils of wires, with a decorated buffer terminal with a collar just above. At the back of the torc, there was a ‘double gold plate of oblong form’ (Bingley 2015, 75) and although this plate is clearly visible in the two drawings (Figs. 3 & 4) of the torc (provided by two of Bingley’s informants), this back plate is not visible in either of the, albeit poor, photographs (Figs. 1 & 2).

The back plate was, however, ‘attested to separately by both main informants’ (Bingley 2015, 76) and would perhaps be similar to the repair seen on the Snettisham Grotesque torc (Fig. 7).

Of interest, the neck ring coils appear to have been twisted both anti-clockwise and clockwise, an unusual feature with an Iron Age parallel in the South West Norfolk torc (Fig. 5). The terminal faces are described as having been flat faced, or slightly convex, with the wire coils neatly fitting the terminals. No mention was made of any holes in the terminal faces, such holes might be expected in a cast terminal torc of this form.

When asked to comment, the British Museum stated that ‘the form is very different from other British finds’ (Bingley 2015, 76). Bingley himself recorded that he thought the torc to have ‘affinities’ with the terminal type seen on the torcs and bracelets of Waldalgesheim (Fig. 6).

A conundrum

With such limited information, there is little of certainty that can be said of this torc. I have spent months searching auction and museum catalogues, internet sites, reverse image searches, etc (both for present listings or, via the Wayback Machine, for previous ones) and I can find no trace of the West Tilbury torc, or anything like it. A social media request on multiple platforms for information has, to date, yielded no further information.

The style is undoubtedly highly unusual, with terminals that echo torcs such as those from Waldalgesheim (Fig. 6), but a neck ring that is more reminiscent of the Snettisham Grotesque torc, or South West Norfolk torc (Fig. 7). The South West Norfolk torc neck ring is also made from three coils which – as noted above – have been twisted in opposite directions: an unusual and distinctive feature rarely seen in torcs found in Britain and Ireland.

The terminals of the West Tilbury torc are more reminiscent of replicas sold widely on the internet (Fig. 8), although the neck ring is wrong for these replicas.

I have to admit that my first thought was that this torc was fake, or a replica: the strange design, undiagnostic photos, untraceable internet sales, etc suggest that this torc was perhaps a replica used to fool someone, to cash in on an unsuspecting buyer. Or perhaps it was a tall tale created to entertain. But there are two aspects which stop me from buying into this scenario.

The first is the weight: at 1020g it is exactly the weight you would expect for an Iron Age gold alloy torc of this size and compares well to torcs like those from Ipswich and Snettisham. It could, however, always be possible that the torc was a replica created in gold alloy: this might also explain the reluctance of any purchaser to acquire the torc, its apparent sold price of £30,000 being way below what might be expected, even for an illegal sale to a buyer who knew that the sale options of the seller were limited.

The second aspect of the West Tilbury torc that makes me think it could be a real find, is the opposite twisted neck ring coils: in most torcs (for example the Snettisham Great and Hoard L7 and L20 torcs and the Newark torc etc) the wires are all wound in the same direction across the neck ring. Only in the South West Norfolk torc do we have opposite twisted wire coils and, similar again to the West Tilbury torc, only three coils.. It would be easy to suggest that the West Tilbury torc, if it was a fake, was made to mimic the South West Norfolk torc, were it not for the fact that the South West Norfolk Torc was only found in 2003, some three years after the West Tilbury torc. However, Bingley’s 2004 request for further information would post-date the South West Norfolk torc’s finding and so a copy is still potentially possible.

The torc also has echoes of another torc that has recently come to light. The Pulborough Area torc, found in 2019 in Sussex, is a contested torc thought either to be a fake, or a genuine or planted original (Machling et al 2023, Machling & Fregni 2024, Adams et al 2024). It should be said, however, that the West Tilbury torc would appear, from Figure 2, to be more precisely made and finished and has reasonable Iron Age parallels in the wire neck ring, and weight, to make it not impossible that it is genuine. If it is real, with the terminal form, and twisted coil neck ring, its closest dating parallels are likely to be earlier, rather than later Iron Age, although this is by no means certain.

As such, at present we need to treat this torc with a careful and tentative understanding that it may be a genuine Iron Age torc from the West Tilbury area of Essex. Unfortunately, unless further information about the torc comes to light, it will always be impossible to tell for sure.

If anyone knows anything further about this torc or its current whereabouts, please do contact me. I can guarantee 100% confidentiality and anonymity. I would just like to know more about it, nothing more.

Acknowledgements

With huge thanks to Andrew Fitzpatrick who tipped me off about this torc, and set me off on the hunt for it. My thanks also go to the Thurrock Local History Society for sending a copy of their Panorama journal and to the late Randal Bingley for making sure this torc was not ignored or forgotten. Local societies are a crucial part of the archaeological world and, without their diligence in recording the events above, we would be none the wiser about the existence of this torc.

References

Adams, S., Craddock, P., Hook, D., La Niece, S., Meeks, N., O’Flynn, D. and Perucchetti, L. 2024 The Pulborough Gold Torc: a 4th to 3rd century BCE artefact of European significance, Internet Archaeology 67.

Bingley, R. 2004. Reputed torc find. Panorama: The journal of the Thurrock Local History Society 41, 47.

Bingley, R. 2015. The West Tilbury gold torc: a confirmatory note. Panorama: The journal of the Thurrock Local History Society 53, 70-76.

Joachim, H-E. 1995. Waldalgesheim: Das Grab einer keltischen Furstin (Kataloge des Rheinischen Landesmuseums Bonn) Rheinland-Verlag in Kommission bei R. Habelt

Machling, T. & Fregni, G. 2024. Fake or fortunate? The insecure provenance of the ‘Pulborough Area’ torc. DOI 10.5281/zenodo.13911434

Machling, T., Williamson, R. & Fregni, G. 2023. ‘All the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order’: The riddle of the ‘Pulborough Area’ torc from Sussex. DOI 10.5281/zenodo.10511405

Tripp, C. J. 2018. Thurrock’s Deeper Past: a confluence of time. Archeopress

Just wanted to say kudos for your work on this. Very impressive labour of love (or hate, as the case may be). Incidentally, I think you’re too quick to give up on your Boudica thesis. I enjoyed Echolands too, but I thought his arguments for his St Albans site were hardly conclusive.

Yahoo Mail: Search, organise, conquer

LikeLike