by Tess Machling

[A download/print PDF version can be found at the end of the paper]. This paper can be cited as DOI 10.5281/zenodo.15181346.

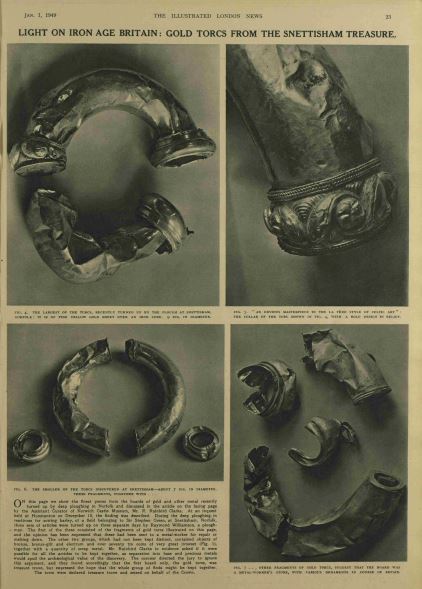

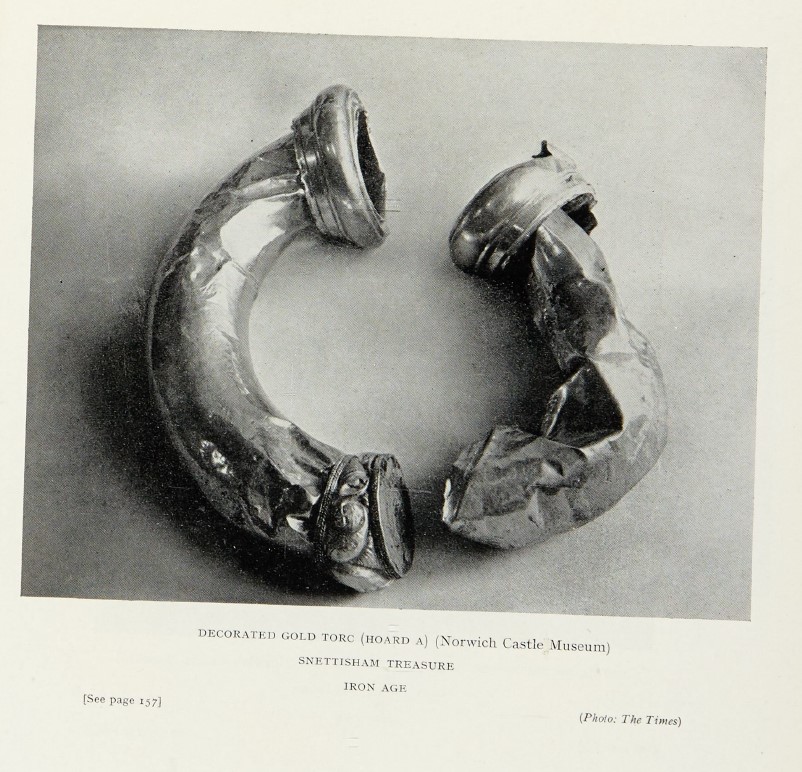

While I was perusing the Snettisham volumes, I happened to notice an image of a tubular torc from Hoard A at Snettisham, torc A.1. This torc was found by Ray Williamson in 1948, one of the first torcs found at Snettisham. When found – as can be seen from a 1949 newspaper article and from a photo in a paper by Clarke from 1951 – this torc was pretty bashed up (understandable really for a gold tube made from sheet only about 0.1mm thick):

Anyway, the torc as you see it today is very different. The squished bit is no longer squished! So what happened?

In the earlier 20th century – and as discussed in the Snettisham volumes – conservation theory was very different to what it is today, and Hoard A was ‘highly restored’ as was the practice at the time (Shearman & Hockey 2024, 413). Sadly, it is uncertain exactly what work was done as the paperwork regarding these post-war treatment interventions cannot be located (Shearman & Hockey 2024, 413). But whatever was done, it can easily be seen that torc A.1 was much ‘improved’!!

A clue, however, might be found in the acknowledgements of a Snettisham paper from 1954, in which Roy Rainbird-Clarke mentioned three people: “The investigation of technical problems connected with the find has owed much to the ever ready help of Dr H. J. Plenderleith, Dr A. A. Moss and especially to numerous discussions with Mr H. Maryon”. (Clarke 1954, 72).

Plenderleith was an archaeologist and conservator at the British Museum, Moss had recently been employed at the British Museum Research Laboratory. But it is Herbert Maryon who is of most interest to me in this case. Maryon was a renowned sculptor, goldsmith, archaeologist and specialist in metalworking techniques. From 1944 to 1961 he worked under Prenderleith as a conservator at the British Museum, most famously working on the Sutton Hoo material.

Maryon appears to have taken a particular interest in tubular torcs and had researched and written about the Broighter torc from Ireland (Maryon 1938). In 1954 he also dismantled the Torrs pony cap horns to understand how they were made (Atkinson & Piggott 1955). So did Maryon work on the Snettisham tubular torcs? Almost certainly, although we do not know exactly what he did.

But back to torc A.1…

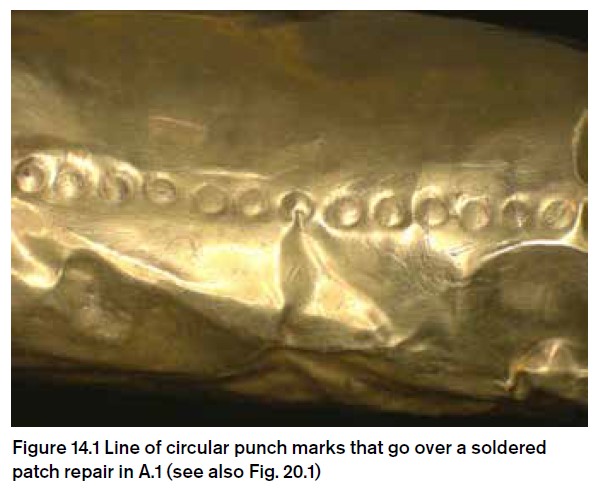

Why this torc in particular caught my interest was mention of “a small square ancient repair patch, soldered into and flush with, the tube” (Farley et al 2024, 159). This patch is located on the interior of one of the pieces of torc A.1.

I had seen a similar patch before on the Snettisham Hoard E.1c armring, which had been found attached to the Snettisham Great torc. The armring has a small square patch on the exterior face of the bracelet and, although the armring patch is slightly smaller than the torc A.1 patch (this patch appear to be about 10mm x 10mm, whereas the armring patch is only about 5mm x 5mm) they are comparable in shape and technique.

I’ll be honest in that I really wasn’t sure what to make of the armring patch when I first saw it. It really didn’t look right for an ancient repair and had an element of clumsiness to it that I wouldn’t expect from an Iron Age goldsmith: for one, it was square, which is a really weird shape for the Iron Age. Also, Iron Age patches tend to be riveted or soldered over the top, whereas this just appeared to be an inserted square of gold alloy, soldered shut around the edges. I also couldn’t see a reason that would require such a patch: even a caved-in sheet form could be righted without resort to taking a chunk out! An early 20th century conservation activity had crossed my mind…

And now there were two of them: the E.1c armring and the A.1 torc. I checked the record for the Snettisham E.1c bracelet in the Snettisham books and there was no mention of a patch: clearly they hadn’t spotted it. But they obviously believe the one patch they have seen, on torc A.1, is ‘ancient’ (Farley et al 2024, 159).

I have to say, I’m not convinced these are ancient: both patches are in places which would be good for investigation. In the armring, this hole would allow a good look inside and on the torc, Clarke describes trying to work out (no doubt ably assisted by Maryon) whether the punched circles were purely decorative or had a technological function (Clarke 1954, 40): such a small trap door would be highly useful in such an endeavour. It is also possible that the opening could have assisted in reconstructing the crushed torc: such a centrally-located tool-hole would be very useful. Maryon, as a skilled goldsmith, would have been more than capable of carrying out both.

Unless the post-war paperwork can be found for the works carried out on the 1940s and 1950s Snettisham material I suspect it will be very tricky to ever know for sure, although I have to say that on the balance of probability, I don’t think these small patches really are ancient at all…

What do you think? As ever it’s good to torc…

References

Atkinson, R.J.C. & Piggott, S. 1955. ‘V.—The Torrs Chamfrein’, Archaeologia, 96, pp. 197–235.

Clarke, R.R. 1951. Notes on Recent Archaeological discoveries in Norfolk, 1943-48. Norfolk Archaeology.

Clarke, R.R. 1954. The early Iron Age treasure from Snettisham, Norfolk. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 20, 27–86

Farley, J., Joy, J. & Davies, J. (with contributions by N. Meeks, F. Shearman and S. Adams). 2024. Iron Age hoards and other metalwork. In Farley, J & Joy, J. (eds). The Snettisham Hoards. British Museum Research Publication 225, 158-353. London: The British Museum Press.

Maryon, H. 1938: The technical methods of the Irish smiths in the Bronze and Early Iron Ages. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 44C, 181–228.

Shearman, F & Hockey, M. 2024. Conservation of the Snettisham torcs. In Farley, J & Joy, J. (eds). The Snettisham Hoards. British Museum Research Publication 225, 413-418. London: The British Museum Press.