by Tess Machling

[A download/print PDF version can be found at the end of the paper]

Although I am in no way a goldsmith, I do have the kind of family lineage that suggests my dalliances with Iron Age gold might not just be a lucky co-incidence. Having been to the Goldsmiths’ Fair in Goldsmiths Hall this week, I felt inspired to write a little about my family background…

The Briaults

My family goldsmith story starts in at least 1722, when my 6 x great grandfather, Louis Briault, was born in Saint Maixent L’Ecole in the Poitiers region of France. He was the son of Jean Briault, who had been born in 1687, himself the son of another Jean, who had been born in 1660, also in Saint Maixent. As far as we know, both father and son Jean were goldsmiths, but we definitely know that Louis was.

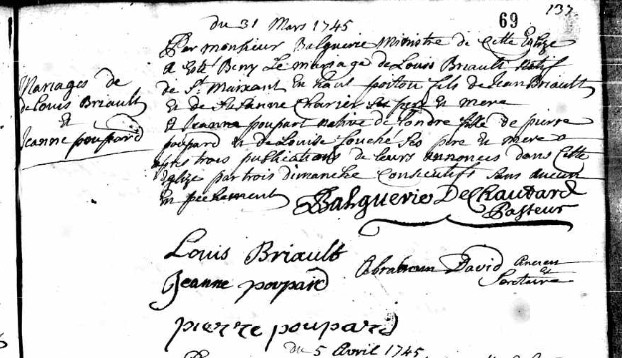

By 1745, as happened with so many Protestant Huguenots, Louis had fled France and was living in the Spitalfields area of London. He married Jeanne Poupard (who had been born in London to French parents) at the Patente church in Spitalfields on 31st March of that year. Louis and Jeanne’s son, John/Jean, later described as a ‘jeweller of Spitalfields, London’ was born in 1750.

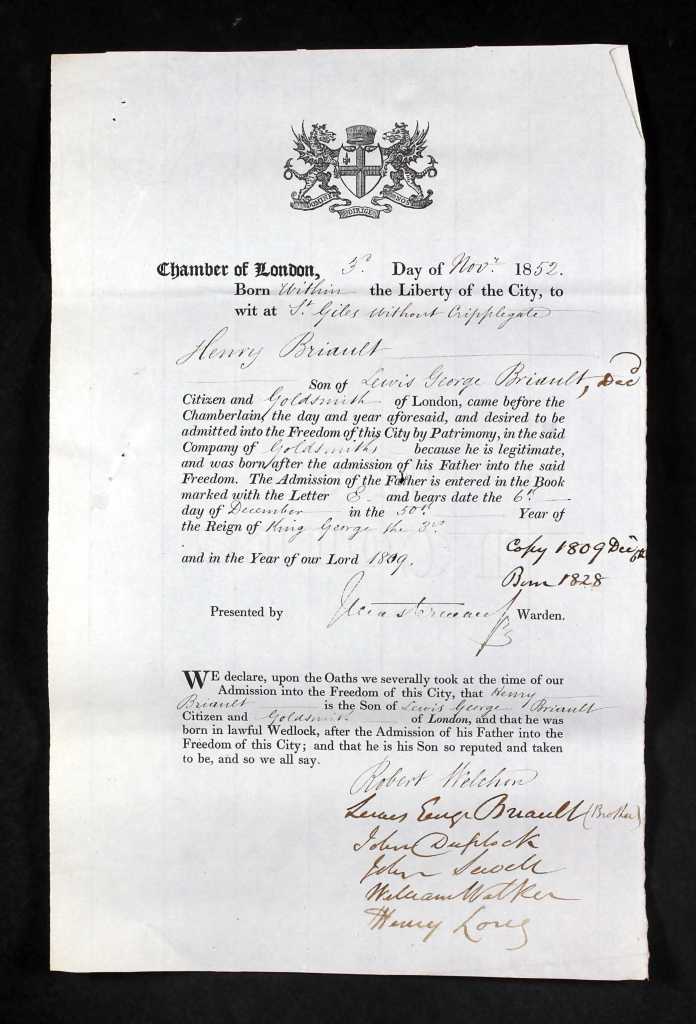

John/Jean’s son, Lewis George was born in 1788, and apprenticed as a goldsmith in 1802, and Lewis George’s son, Henry (born in 1828), was apprenticed and working as a silversmith in 1851. I don’t have much detail about the lives of these early Briault goldsmiths, apart from knowing their profession and that they were working in London, mainly in the Spitalfields/East London area.

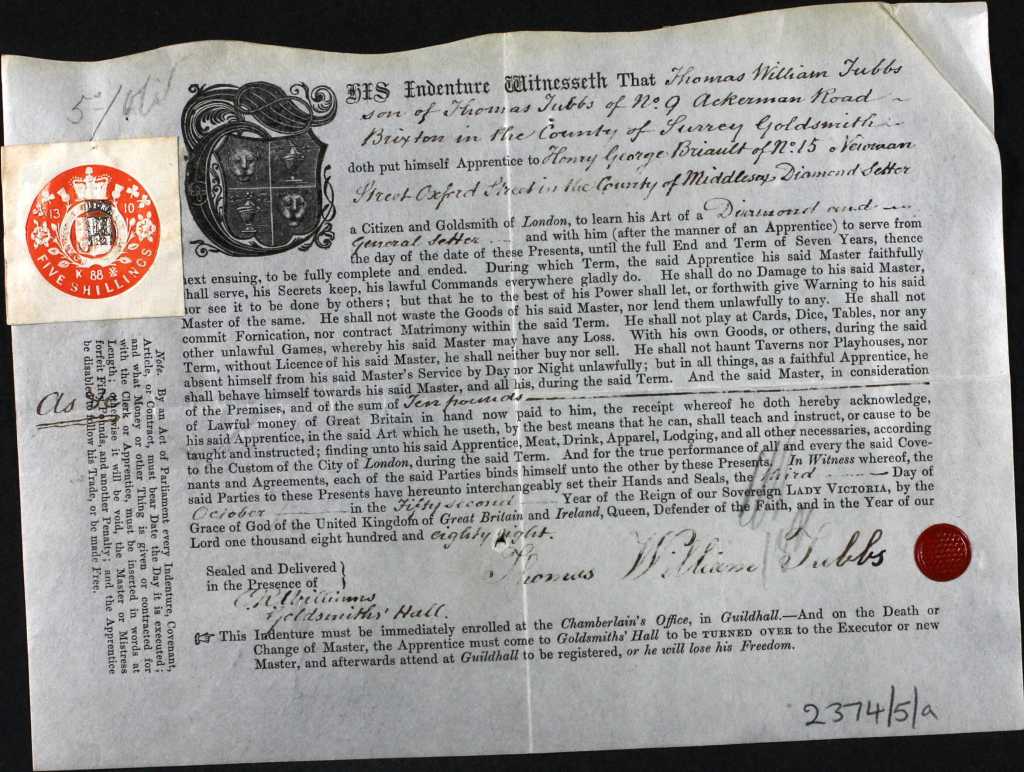

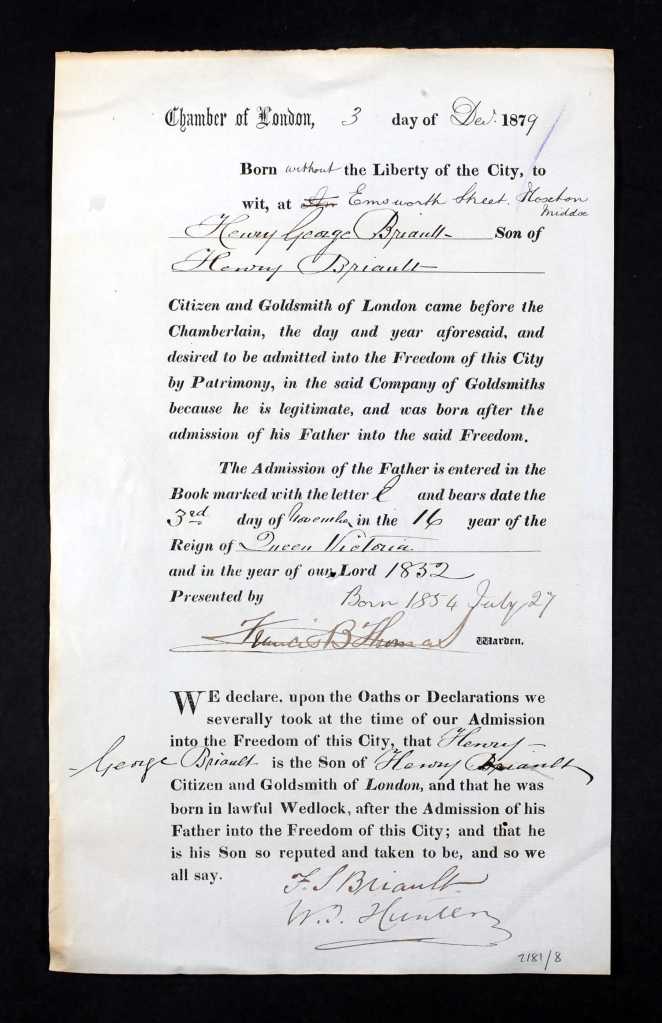

In 1854, Henry’s son, Henry George, was born, and seems to have followed the family tradition, being named as master to a Thomas Tubbs in the latter’s diamond setter apprenticeship documents from 1888.

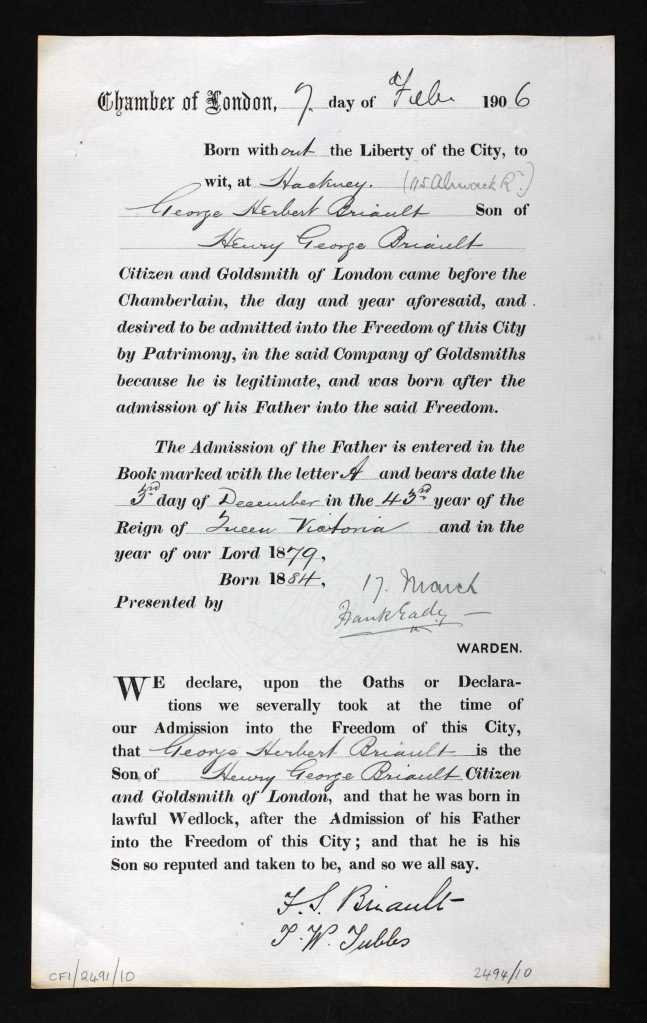

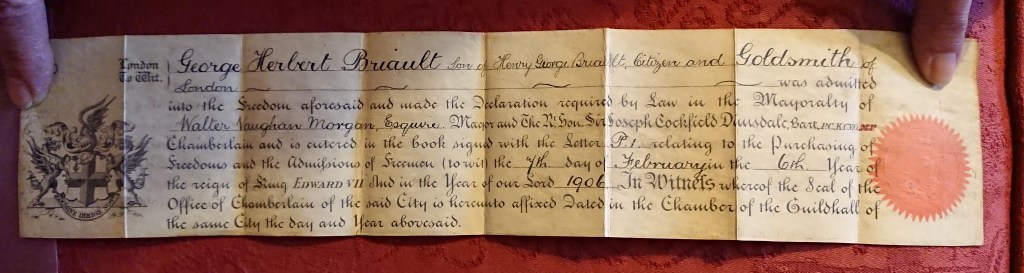

My great grandfather, George Herbert Briault, (Henry George’s son) was born in 1884 in Hackney, and continued in the family tradition of diamond setting, working first in London, and then Brighton, in the first part of the 20th century.

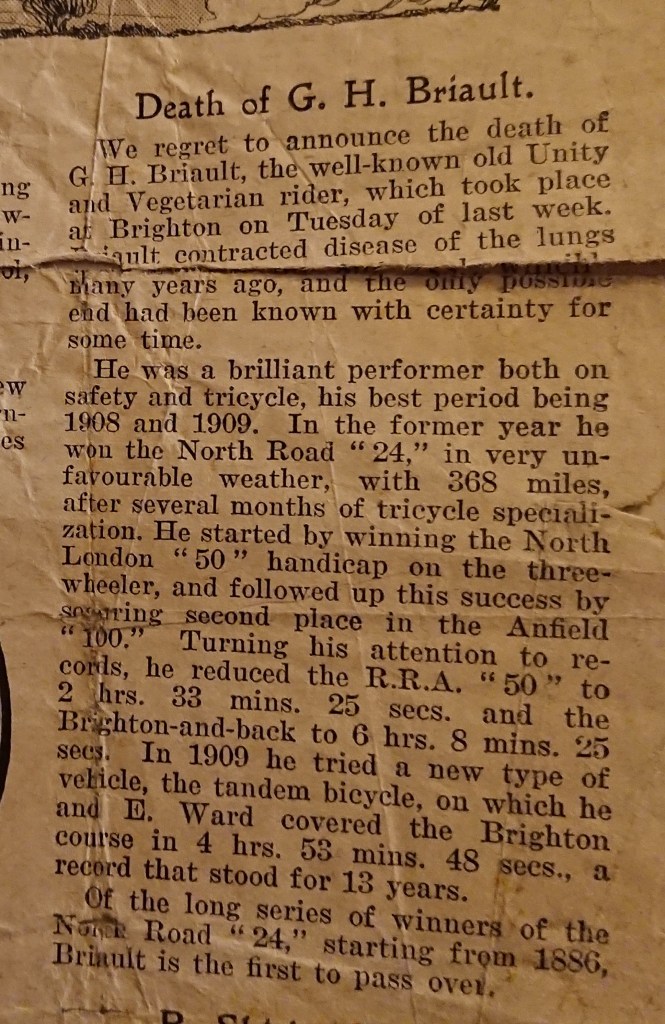

We have documents, going back to Lewis George Briault in 1788, that show that father to son – for at least 200 years – were members of the Goldsmiths’ Company and given the Freedom of the City of London, with all the sheep driving privileges that that entailed!! Unfortunately, that goldsmithing tradition ended in 1926, when my great-grandad George Herbert died, at only aged 40, from complications of pulmonary tuberculosis: the family story being that he was earlier gassed, whilst working in skilled munitions, in the first World War.

Being a closer relative, we do know quite a lot about George Herbert who seems to have been an incredible man by all accounts. He worked on the setting of the infamous Cullinan diamonds in both the Imperial State Crown and the sceptre (and, yes, I fully accept the dark and shameful history of this gem and its acquisition).

As well as being a goldsmith, George Herbert was also a champion cyclist, and the holder of numerous world records in the 1900s, often cycling from London to Brighton and back at speeds that almost all would find daunting, even in modern times! To do it in tweed, on an old style bike, and on uneven roads was even more impressive. He was also noted as being a vegetarian, riding for the Vegetarian Cycling club, an organisation which still exists to this day. [I often think that he would be delighted to know that his granddaughter, great granddaughter and great, great granddaughter are also veggies!]

But I digress, the long and the short is that, when George Herbert died, so did the (at least) 300 year old line of father to son goldsmiths, silversmiths and diamond setters. George Herbert’s young children were packed off to boarding school, paid for by the Goldsmiths’ Company and, although their Freedoms carried on for another generation, by the time of my mum, Jacqueline Briault, we were no longer goldsmiths, neither by practice nor patrimony. The other aspect to note is that throughout the 300 years, they were not rich, with wills that show they left almost nothing. Despite being hugely skilled, and with family knowledge and connections, the craft then, as often now, did not create fortunes.

The Goldsmiths’ Fair 2025

Thanks to the very generous gift of a ticket given to me by my friend, and Torc Collective member, Abigail Brown, I was able to attend the Goldsmiths’ Fair at Goldsmiths Hall, in London this week. The array of work on show was incredible and the range of skills and techniques impressive.

But what affected me the most was the fact that I was retracing the steps of my ancient family, by standing in the places in Goldsmiths’ Hall where they had once stood, and seeing some of the things that they had once seen. I was in the very place that had tied at least 200 years of Briault goldsmiths to each other, close to their London homes and workshops. But it was also a place relevant to not just my Briault line: many of the brothers, nephews, uncles, etc of my ancestors also worked in the craft. It was certainly quite the family trade!!

To say that the building is impressive is an understatement and the wealth and power still held within these walls cannot be overestimated: it is still the home of gold and it’s still an extremely rich members’ club. In archaeological terms, the Goldsmiths’ link is most obvious in the frequent gifts of cash from the company, which help buy many Treasure finds, like the Newark torc, for the nation.

I have also been digging a little further and have discovered that the Goldsmiths’ Company archives contain several files that relate to my illustrious ancestors, so that will be my next foray into Goldsmiths’ land.

It does fill me with pride to be carrying on the Briault gold tradition, albeit in research rather than practice: not bad for a family of refugees (the term was first coined for the Huguenots réfugiés) who fled France in the early 18th century.

Postscript

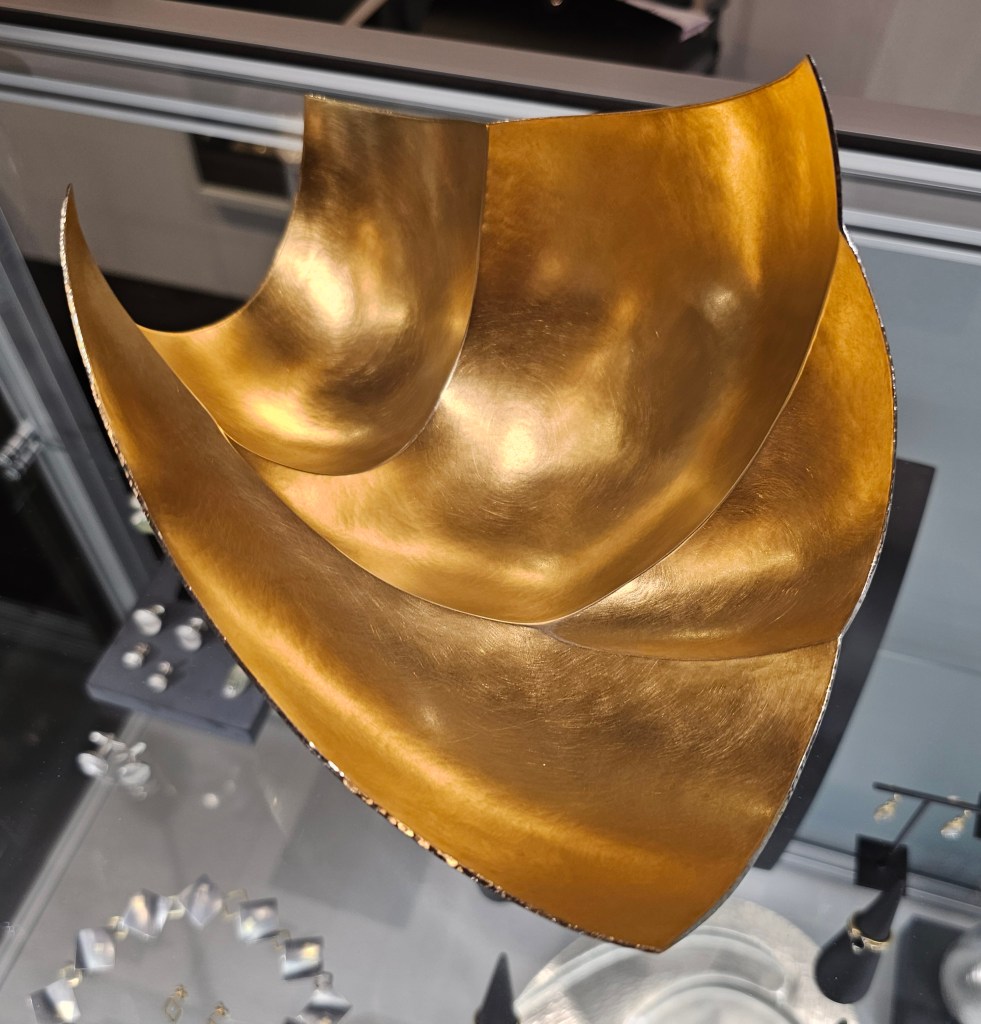

In 2020, during lockdown, I bought a 10g piece of fine gold to get a feel for the material and, since that time – along with many students, friends and colleagues – myself, my mum and my daughter have all had a chance to work gold. I like to think that the male Briault goldsmiths of the past might be proud… or perhaps completely confused about the women of their direct line doing something so audacious!

But I do hope they’d think it was good to torc!

Really interesting article, which I read as another descendent of Huguenots (as far as stories go). My family, Rosher / Rosier, appears to have been allied to the weavers trades back then.

LikeLike

Thank you. 😊 might be worth talking to the Weaver’s guild?

LikeLike

What a fab blog. Thoroughly enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Thank you 😊

LikeLike