by Tess Machling

[A download/print PDF version can be found at the end of the paper]

Abstract

With the boom in detecting tourism, and with mass detecting rallies being held across the UK, increasingly large numbers of finds are being exported overseas, never to be seen again. This export of our shared national heritage is becoming big business with, according to Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) figures for 2023, 26,548 detected artefacts and an additional 75 Treasure finds, being sent overseas in 2023.

Introduction

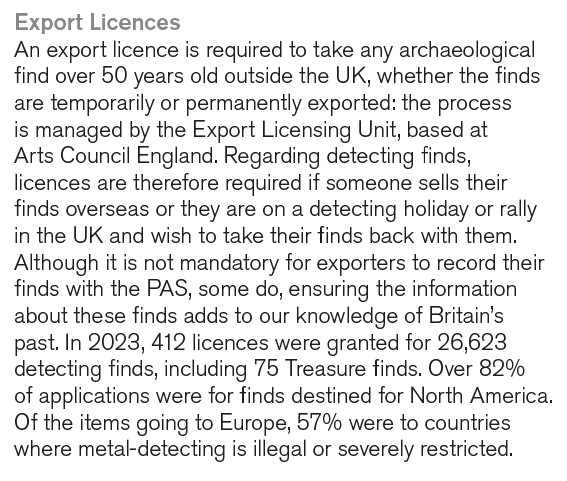

Within the UK, any find over 50 years old that someone wishes to take from the UK, needs an export licence. These licences are administrated by Arts Council England, on behalf of the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport. They are given for free and as such they – and the process that grants them – are another hidden cost of the current metal detecting situation, a cost again not borne by the detecting community. As stated above in the 2023 PAS Annual Report, 82% of these 26,623 exported detected finds go to North America, with 18% going elsewhere in the world, mostly Europe.

Export Licences

Specific permission is required before certain works of art, antiques and collectors’ items, known as ‘objects of cultural interest’, can be exported from the UK. The evidence of this permission is an export licence. The process is set out in the Procedures for Exporters 2024, Issue 1 document and it is well worth reading in full. But, I’ll attempt to precis it below.

Some types of cultural export are covered by an Open General Export License (OGEL). However, all archaeological material found in UK soil or territorial waters, and which is over 50 years old, requires an Individual Export Licence (IEL), unless it is exported by a larger organisation, dealer, or museum moving objects on loan, etc who hold an Open Individual Export Licence (OIEL). In practice, the Individual Export Licence will need to be applied for, for all detected finds over 50 years old.

When an export licence is applied for, should the find be deemed important, in the words of the guidance ‘your application may be referred to an Expert Adviser (usually a director, senior keeper or curator in a national museum or gallery). The Expert Adviser must consider whether they believe your object may be a national treasure … before an export licence can be issued’.

For archaeology, this Expert Advisor is the relevant curator at the one of the National Museums, i.e. National Museums Wales, the British Museum or National Museums Scotland. Objects are deemed to be ‘national treasures’ if they comply with at least one of the Waverley criteria (see below).

Expert advisers

I’m taking the following from the Procedures for Exporters 2024, Issue 1: If the Expert Adviser objects to the granting of an export licence, the Export Licensing Unit will refer the licence application to the Reviewing Committee. In cases of doubt, Expert Advisers will object, and the Reviewing Committee will consider whether an object meets one or more of the Waverley criteria. If the Expert Adviser does not consider an object meets the criteria, then an export licence will normally be granted.

However, this paragraph in the guidance is telling and suggests that, for whatever reason, many archaeological finds may be being waived through to export.

‘Expert Advisers only rarely object to the granting of an export licence on grounds that they are believed to be national treasures. Usually, Expert Advisers object to the granting of licences for about 25 to 50 objects each year out of a total of approximately 25,000 objects referred to them’.

The Waverley Criteria

The Waverley Criteria are used to assess whether an object should be considered a national treasure and are assigned by the Expert Advisers. An object can meet one or more of the criteria, and each of them has equal weight, but only needs to meet one of the criteria to be considered a national treasure.

Waverley 1: History: Is it closely connected with our history and national life?

Waverley 2: Aesthetics: Is it of outstanding aesthetic importance?

Waverley 3: Scholarship: Is it of outstanding significance for the study of some particular branch of art, learning or history?

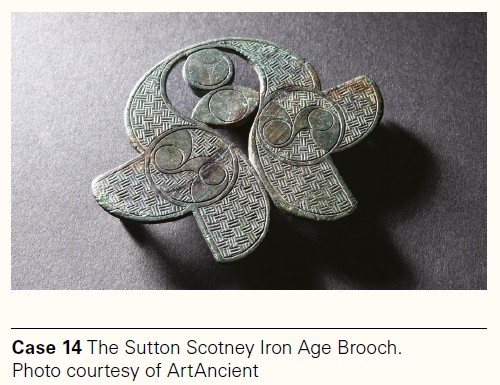

The minutes of the Reviewing Committee can be found online and they make for very interesting reading. Three artefacts in the Annual Report on the Export of Objects of Cultural Interest 2024-25 caught my eye: Case 4, a unique Iron Age gold coin from Hampshire; Case 7, a small gold torc of unknown provenance, and Case 14, an Iron Age brooch from Sutton Scotney. The coin was valued at £20,720, export was blocked and it was bought by the British Museum. The brooch, valued at £22,500, had its export deferred for three months to allow someone the option to buy it: the Hampshire Cultural Trust expressed an interest, started fundraising, but then the owners donated the brooch to the HCT… what a palaver, even if a good result! The small torc, however, was not such a happy tale.

Case 7

Valued at £54,000 and intended for export to France, this gorgeous little torc – probably as it did not have a known UK provenance – was deemed not to meet either Waverley Criteria 1 or 2. It did meet Waverley 3 as there was ‘a scarcity of knowledge about this type of object, and further research was necessary to learn how it may have been used and by whom. They [the committee] noted that the torc was unique in its diminutive size, suggesting that it could have been made to be worn around a child’s neck, rather than an adult’s arm’.

As such, the export licence was deferred for two months while interest was sought from museums. The torc was widely reported in the press in September 2024, with a deadline for expressions of interest set for November of that year. However, by the end of the period ‘no offer to purchase the torc had been made. An export licence was therefore issued’ and the torc was never seen again…

Now obviously, as an Iron Age gold specialist, I’m going to be gutted about any torc that’s been lost, but this one was really special. Even without a provenance, the form showed it was clearly ‘of these islands’ and, as any of you who have read my previous blogs know, provenance and context are rare things in torc studies so this wasn’t a deal-breaker for me.

It had been intentionally curled into a 72mm spiral bracelet, from a small, 100mm diameter, perhaps child sized, neck ring or arm ring …and that hadn’t been seen before. The purity of the gold alloy, at 97% gold, was also of interest: most torcs aren’t of such high purity alloy and this might suggest that it had been made from electrum (a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver). The form, with ring terminals and a twisted rod band, would also suggest it was made within these islands, perhaps from local metal.

Put together, even though it didn’t have a secure provenance (we just do not know where it came from: it could be an illicit detected find that had been provenance-washed, or something from an antiquarian collection), the twisted rod band, the form, the alloy and the size meant there was a lot of potential work that could have been done on this torc. But that opportunity has now been lost: all I’ve now got to work with is the photo above and a few lines of text…

Detecting exports

Many export licence applications come from detected finds, found in the UK and either sold to or taken overseas. I can’t help thinking that the ‘25,000 objects referred’ to the export Expert Advisers every year, largely comprises detected finds. Indeed this number compares well with the ‘412 licences [that] were granted for 26,623 detecting finds’ mentioned in the 2023 PAS Annual Report. I will go in to these huge figures in more detail later, but in the meantime: where are all these exported finds coming from?

Detecting tourism and rallies

Although we don’t actually know how many people are visiting the UK to detect each year, many are arriving to take part in large commercial rallies. Figures from the largest rally, Detectival, suggest over 1000 participants from 37 different countries took part in their 2025 event. Indeed, at this rally finders were ‘able to apply for an Export Licence’ while they were still onsite.

[Large rallies are worthy of a short mention here. Often commercially run, and targeted at areas of known historic interest, these events are a law unto themselves: many important finds, such as the Malmesbury Bronze Age bracelet hoard have ended up being excavated without archaeological supervision, and the huge quantities of finds recovered are utterly unmanageable. In my view, rallies are probably the activity in the current metal detecting system that most urgently needs regulation].

Although the Portable Antiquities Scheme does not attend rallies, recently a commercial organisation, Middle Ground Archaeology, has stepped in to fill the gap. The justification for offering this service is that they offer ‘a pragmatic approach to ensure as much information as possible is recorded at detecting rallies’.

However, I have to admit that this makes me extremely queasy. I think this approach is providing unsupportable ‘archaeology-washing’ for an activity that the Portable Antiquities Scheme has stepped away from, because rallies ‘do not provide the ideal circumstances for PAS staff to record finds in the field’ (to me this always sounded like a very polite way of saying that rallies are an extremely under-resourced, maniacally busy and hostile environment for the PAS’s Finds Liaison Officers (FLOs) to have to operate in). If we play along with this type of event, providing archaeological ‘cover’, then there will never be any reason for the locust-like, artefact-stripping, commercial rally system to be regulated.

In addition to rallies, many organisations now offer detecting package holidays: bed, board, detecting, and export licences, all for one easy payment. One Colchester based organisation will even sort out your export licences if you are not detecting with them: ‘you mail or drop off your finds to us and we do the rest of the work… We apply for an export license and if approved you can either get the finds mailed to you or you can pick them up on your next trip’ . Hmmm, archaeological finds flying around in the post between here and the rest of the world. Doesn’t bear thinking about really, does it? But it’s all perfectly legal…

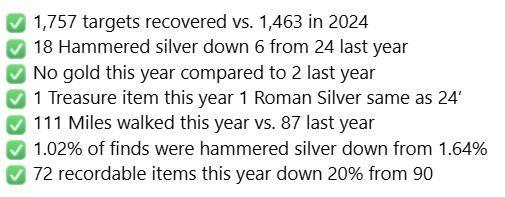

To illustrate the impact that such detecting tourism may be having, one Facebook poster from the USA, who regularly posts about his detecting holidays, reported that he had found the following on his latest 2024 trip to the UK:

From images attached to his post – which show the finds laid out on standard export licence grids – it is obvious that he was intending to export at least 75 of these finds to his home in the USA. If his haul of 75 items is typical, if we divide the number of exported finds reported in the 2023 PAS report, by the number of his items, it is possible to suggest that around 350 detecting tourists a year are exporting their finds overseas. This fits well with the PAS 2023 figure of 412 cases.

Export numbers

So now we come to those figures – the 26,623 finds (including 75 Treasure finds) exported from the UK in 2023. Interestingly, it is only in the latest, 2023, PAS Annual Report that export licence numbers have been given.

This might suggest that this issue has only had numbers worthy of reporting relatively recently: this would fit with the overall figures for detected finds, which have seen a steep increase in recent years, matched by a decline in the number of finds being bought by museums or donated to museums by finders. Are exports following this trend, with increasing numbers of detected finds being sold/taken abroad?

Anyway, to get back to the numbers.

The 2023 PAS report mentions that there were 412 export licenses granted to detected finds cases in 2023. If compared to the figures given in the report on the Export of Objects of Cultural Interest 2024-25, where there was a total of 5075 individual licences granted from May 2023 to April 2024, it would suggest that detected finds comprise c.8% of the total of all cases of cultural interest objects! When you consider that various antiques, jewellery etc are also covered within these licences, this appears to be a huge proportion of export licenses going on detected finds!

As to the overall figure of 26,623 finds, we do not know when these objects were found: like Treasure cases, they could be finds made over a number of years, although the tallies of the USA detectorist, and the evidence from detecting tourism organisations, would suggest that the majority are fairly instantaneous exports, being made soon after finding. The other thing we do not know is whether these finds were ever recorded on the PAS (remember, that unless Treasure, recording is entirely voluntary), so they might be extra to the 74,506 finds recorded by PAS in 2023.

However, if they were all recorded by PAS (our American detecting tourist recorded all his exported finds) then the 26,548 non-Treasure exported finds are equivalent to over ONE THIRD of the number of recorded detected artefacts found in England and Wales in 2023 having been exported overseas.

I’ll say that again. One third exported overseas.

If this is true, this is a truly shocking number. What we also know is that the number of Treasure artefacts exported, although some won’t have been found in 2023, is equivalent to c.6% of the 1358 Treasure cases reported in 2023.

If these numbers are repeated in coming years the statistics for the loss of our portable heritage assets, be it through increased exports, reduced acquisitions and reduced donations to museums, or the increasing number of finds taken home to be placed on a shelf, is almost reaching incomprehensible numbers: we are talking tens of thousands of objects per year and over time, many hundreds of thousands of artefacts are now lost from public view.

Summary

Export figures appear to be rising with many thousands of detected finds being exported from the UK in 2023. Aided and abetted by detecting organisations who wish to make this process as smooth as possible, more and more of our shared heritage is leaving these islands, never to be seen again.

One might ask whether this is yet another sign that metal detecting is increasingly becoming a commercial venture, where there is a growing lack of regard for history and more for its cash value on the open market? Well, yes, I would say that the export and acquisition/donation figures suggest that this is indeed the case.

I’ve previously shown with my work on the under-resourced and overstretched PAS, the broken Treasure system and the increasing loss of finds from museum ownership and now – in the case of export licences – that we, the British public, appear to be losing out to the detecting community as our shared national heritage is sold and/or scattered to the four winds.

In an earlier blog, I said that I thought the system was broken, and asked why we were not more concerned. However, having looked further into the detecting system, where:

- less than 4-10% of detectorists are reporting their finds,

- Treasure case numbers are rising by at least 10% a year,

- numbers of non-Treasure finds are rising by thousands each year,

- only c.4% of Treasure finds are donated to museums, and the majority of those are ‘archaeological finds’

- c.50% of Treasure finds are disclaimed,

- only c.25% of Treasure finds are being bought by museums,

- Treasure is costing us £7 million a year,

- c.6% of Treasure finds are being exported,

- c.80,000 non-Treasure finds a year are being handed back to finders and landowners to do with as they wish,

…and potentially where 30% of everything found using detectors is being taken from the country, I now feel that I shouldn’t be asking ‘why we are not more concerned?’, but instead ‘why are we not screaming?’

—————–

For ten years I’ve offered the results of all my research for free and open access. I’m an independent researcher and have no funding, so all museum trips, research visits, writing up, conferences etc are funded by my scraping together savings and lecture fees etc.

Thanks to a few recent changes in circumstance, this is getting more and more difficult for me to fully support and, even though I’ll still be doing everything open access and always will, if you do have a bit of spare cash (…and really only if!!) buying me the occasional ‘coffee’ to support my gold research would be really fabulous. You can buy me a ‘coffee’ here!

11 Replies to “Going… going… gone overseas?”