The next step in this journey will be to go and look at some torcs off display: so far, I have permission to go and look at three of them. But it is by no means a given that I would be granted access. Torcs are not only precious and delicate items, but they obviously also have a considerable monetary value, often into hundreds of thousands of pounds, if not more in some cases. Of course, irrelevant of their monetary value, they are unique items: one offs that are, literally, irreplaceable.

As such, it is not a perfunctory exercise to request and be granted ‘off display’ access: rightly, museums very carefully consider whether torcs should be taken off display, and only on a case-by-case basis, with specific research aims in mind. Rarely have I seen torcs more than once, and only ever if we have a further research question to answer, which we weren’t aware of when we first saw the torc in question.

Curator time is also precious, and each torc visit necessitates the presence of a curator. With more and more museums facing horrendous funding cuts, finding time for curators to sit with researchers is becoming more and more difficult. This is a terrible loss both to the museums – who want their objects to be researched and that research disseminated – and to the research community, whose access will inevitably be restricted.

Looking at torcs

Once permission is granted, a date and time is arranged and the torcs are taken off display and taken to a secure location, where I get to look at them. When we’re with the artefact, I’ve often found that curators want to have a close-up look too, to see certain aspects, or check the conservation/state of the item: I think people imagine that curators often have items off display, but in reality a researcher asking for the artefact may be one of the only times they get to see the objects up-close.

The time you get is as short as possible to achieve the answers needed. Keeping a torc off display for too long obviously means those visiting the museum gallery won’t get to see it for however long I have it all to myself, so it’s important not to dally! ‘Torc days’ are always spent trying to cram in as much data gathering as possible, before the torc goes back on display. To be honest, it’s exhausting!

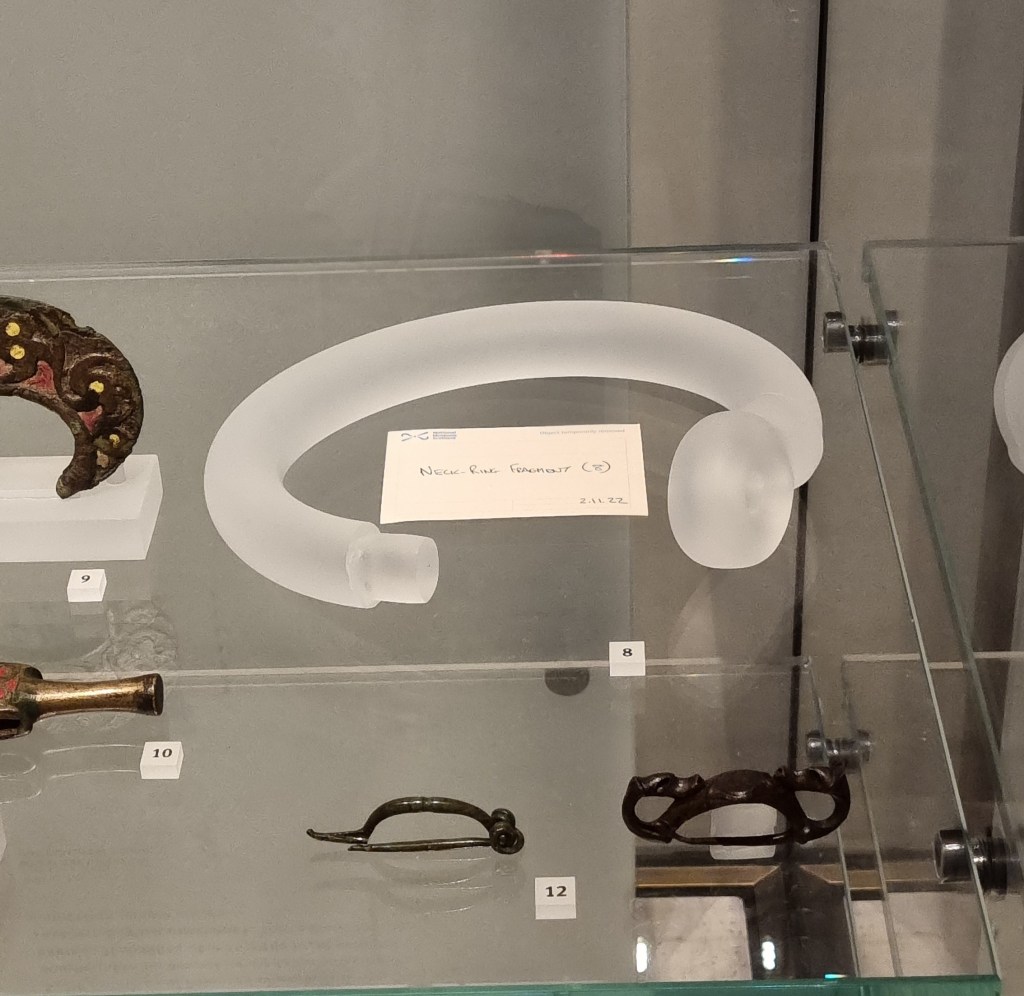

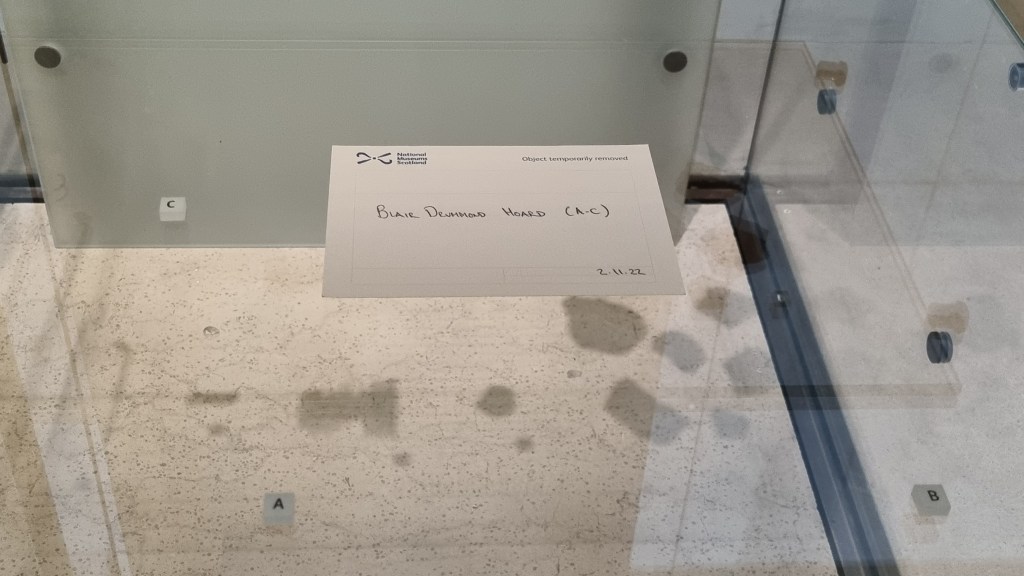

When the torcs arrive they are securely packaged for transit: often the packing itself is a work of art, which I must say, the museum/conservation assistants at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, excel at.

Even having looked at many torcs off display, it is still a privilege that I don’t take for granted: when you wander through a museum and see the empty space in the cabinet and know that this is because the torc has been taken off display just for you, it’s quite a buzz!

Torc examining kit

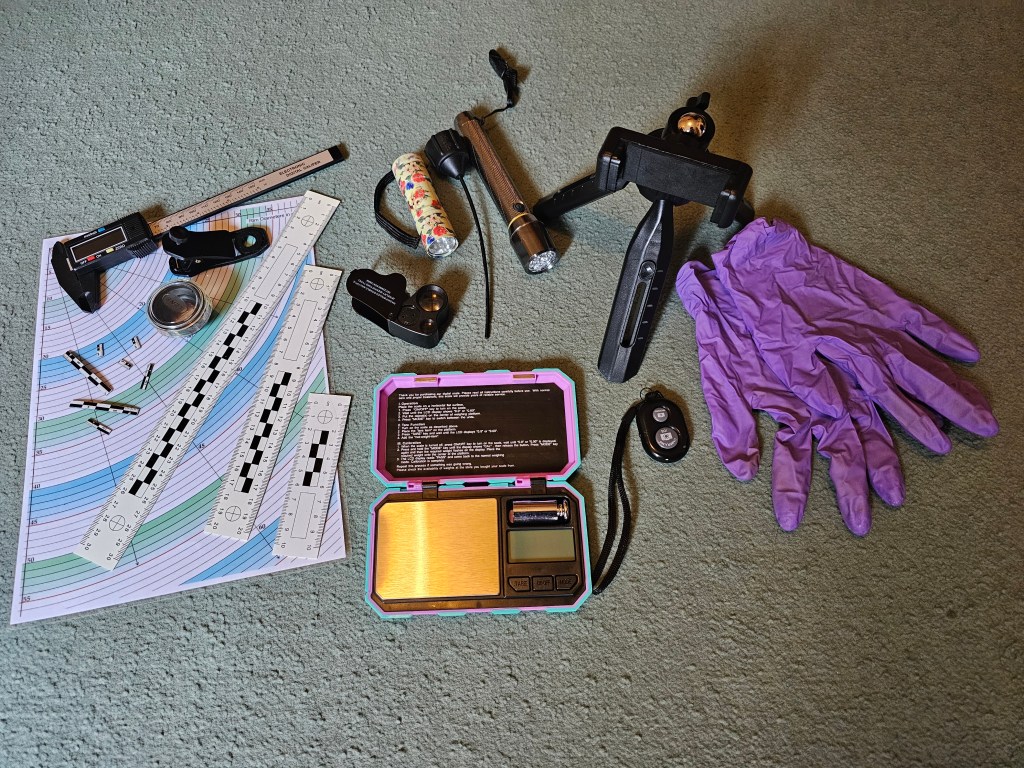

My torc kit used to include a camera, but nowadays I find the camera on my Samsung 23 Ultra mobile phone is more than up to the task, and the kit I carry with me (an extra macro phone camera lens and phone tripod with a remote shutter controller) reflects this.

The rest of the kit comprises measuring and photo scales, both mini and ruler length, a pottery rim measurement chart (useful for working out the original diameters of broken torc pieces) a precise jewellers scale (for smaller pieces), a jewellers lens, torches and electronic rubber-tipped calipers (metal-tipped calipers will scratch gold and so should never be used). I also carry nitrile gloves, which some museums insist upon (some also don’t, which is a valid approach: gold is after all largely inert and wearing gloves can reduce feeling which means items are more likely to be fumbled or dropped!).

Ultimately though, the best bit of kit you have is your eyes: not fancy gadgets or machines that go ping, but just your good-old eyes, and a magnifying lens. It is so important to take time to look at a torc, to take it in and to think about it. What are my first impressions? How might it have been made? How was it compiled? Does it remind me of any other torcs I’ve seen? What is the same, what is different?

This is the most important part of torc examination and will tell you so much about it: you are seeing what the goldsmith who made it saw, and you need to try to think like them to be able to understand what is in front of you. There is also an element of connoisseurship in looking at torcs: you get a ‘feel’ for the torcs and their makers that is often difficult to explain or detail, but can often provide important insights into the torc makers of the Iron Age. You can almost see the individual goldsmith moving the piece around, the proportions that certain individuals favoured, the directions they worked from, the way they used the light to play on the design… and the bits where they went wrong and had to cover it up!

Metrics

The next stage of examination is to record the metrics: lengths, widths and thicknesses of terminals, diameters of wires, neck-ring widths and diameters, tooling marks, weights of everything. It is amazing how often torcs don’t have even the most basic measurements recorded for them. Perhaps a legacy of many of their antiquarian-found origins? or maybe because, as bling/treasure they are overlooked as artefacts requiring the same metrical recording as, say a piece of pottery? A bit of both, I think.

I also usually take hundreds of photos with a scale. Nothing that looks especially fancy, but record shots that will allow me to interrogate the images later, when I have more time.

There will also be specific ‘target’ questions to answer: in the case of the Staffs Five, those immediate questions will be:

- Are any of the torcs cut/ ‘nicked’? (is there any Viking adaption visible?).

- How were the terminals of Glascote and Needwood Forest made? (is the overcast theory sustainable?)

- Is the Alrewas ring (holding the torc bunch together) a circular ring? (less likely to be a re-used terminal) or a teardrop shape? (could be a re-used torc terminal). This might hold clues as to whether it was a Viking bundle.

I’m hoping that seeing these torcs up-close will help to answer these questions, and there’s always a ‘well, will you look at that!’ moment where something is utterly not what you expected!

Soon I shall be off to examine the Staffs Five which will be hugely exciting, but there is a downside: the very necessary security protocols, and obvious security risk, means that I can’t tell anyone when or where I’m going to see torcs. As such, sadly you will have to wait until after they are safely back in their cases to hear what I’ve found…but I’m sure you will understand why (the awful recent theft of the Ely torc and bracelet show just how vulnerable artefacts can be).

Until then, click ‘Subscribe’ to be kept up to date, and keep torcing!

2 Replies to “The Staffordshire Torc Odyssey: 10 Looking at torcs”