by Tess Machling

[A download/print PDF version can be found at the end of the paper]

This paper can be cited as: DOI 10.5281/zenodo.14548720

I’ve been meaning to write this piece for years, but a recent increase in the number of significant archaeological finds which have been removed from the ground, by folks with little or no archaeological training or understanding, has prompted me into action.

In this piece I want to explain why, for me as a torc researcher (torcs are neck rings/arm rings from the Iron Age, about 2000-2300 years ago), my work on these incredible objects is severely hampered by the fact that so few torcs have been archaeologically excavated and why – directly because many torcs are detected or antiquarian finds – the subsequent lack of contextual information has led to dead-ends in many aspects of the research into these magnificent objects. It should also be said that, although this blog is about torcs, it could apply to any type of Treasure find.

By writing this I hope to show – from a researcher’s point of view – why bringing in archaeological specialists the minute you find something significant is not only desirable, but essential. In short, as a detectorist, when you become aware you are dealing with something archaeologically significant, do not – whatever you do – dig it up without professional archaeological guidance or you will destroy, not save, the full evidence of that artefact.

More importantly, by not bringing in the professionals you will certainly damage or destroy the archaeological story that can be told about the artefact or group of artefacts you have found: that includes the loss of the ‘how’, ‘when’ and ‘why’ of its deposition.

Torcs and Treasure

There are around 400-450 Iron Age torcs represented by finds from England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. These 450 include complete torcs (110 are complete), partial torcs (torc halves etc) and pieces of torc (usually wires). Around 50%, by number, of these torc remains are gold rich alloys, with a further around 20% being silver rich and 20% made of copper rich alloys. There are also a couple of iron torcs and one lead one known (please note, these percentages are approximate as, for a number of torcs, the predominant metal in the alloy has yet to be determined).

However, even with approximate figures, the majority – more than 70% – are precious metal alloys. As such, under the Treasure Act 1996 (which applies in England and Wales, different rules apply in Scotland and Northern Ireland) which states that,

“any object at least 300 years old when found which— (i) is not a coin but has metallic content of which at least 10 per cent by weight is precious metal”

all precious metal torcs found in England and Wales will qualify as Treasure finds. I won’t go into the precise details of the Treasure Act process. but these can be found on the Portable Antiquities Scheme website.

However, the 1996 legislation did not apply to all torcs, as more than 20% of them are made from metals which are not classed as precious metals: lead, iron or copper alloys. In 2023, an amendment to the Treasure Act widened the Treasure criteria to include artefacts which provide:

“an exceptional insight into an aspect of national or regional history, archaeology or culture by virtue of one or more of the following: (i) its rarity as an example of its type found in the United Kingdom (ii) the location, region or part of the United Kingdom in which it was found, or (iii) its connection with a particular person or event, or although it does not, on its own, provide such an insight, it is, when found, part of the same find as one or more other objects, and provides such an insight when taken together with those objects.”

Hopefully, this new amendment will cover torcs and so it is possible that any newly found non-precious metal torcs will be included in the new legislation. However, this is yet to be tested. As such, until now, around one fifth of known Iron Age torcs were not covered by Treasure law, with many, such as Shenstone, returned to finders to do with as they wish and which largely became inaccessible for research.

Here I should note that some detectorists and landowners (it should not be forgotten that landowners are an integral part of the detecting community) or antiquarians did – and do – donate their finds to museums and so some torcs, whether precious metal or not, purely by luck and/or generosity, are now in collections that are accessible to research. But finding those torcs that have not been acquired, or which reside in personal collections, is a difficult task: the finders are not always known, or may have moved, the torcs sold or changed ownership.

Until 1996, the common law of Treasure Trove in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland applied. This law stated that the artefact 1) had to be made substantially of gold or silver, 2) had to have been deliberately hidden with the intention of recovery, and 3) that its owner or his heirs had to be unknown. For obvious reasons – oh, if only archaeologists could tell if something was ‘deliberately hidden’!! – in the later 20th century, as archaeological understanding advanced, these rules became notoriously difficult to apply, with the Snettisham torcs receiving much discussion after their excavation in the 1990s (see Stead and Chippindale).

The above is relevant as the various Treasure laws are the mechanism by which torcs have been retained by, or lost from, the accessible archive of public museums. Before we look at the detail of what this has meant, I want to look briefly at ‘Context’: the basis of archaeological practice.

Context

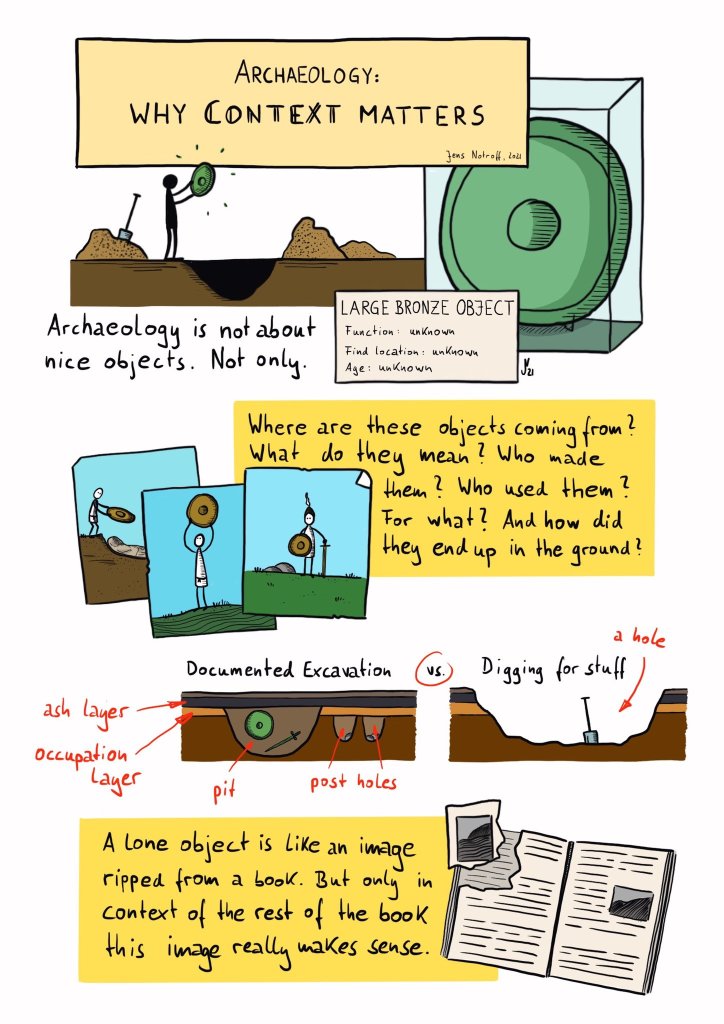

Context is not just artefacts, but literally, the context in which they were found. Context includes the relationship between artefacts and their surroundings, their location and the deposits they came from. It also includes the position of artefacts and material in relation to other archaeology on the site. In terms of artefacts, Jens Notroff on X/Twitter puts it best (Fig, 2):

To record and examine context archaeologists use a range of methods and tools: the work starts before any earth is moved – with documentary information gathered on the site to be examined – and continues on the dig with experienced and highly trained archaeologists collecting, recording and documenting information, samples and finds.

The next stage, post-excavation, uses these records, finds and samples (via an extensive team of specialists and writers) to produce an evidenced narrative about the dig: what was found, what it means and how it fits into what we know about the broader archaeology of the region or period in time. The above hugely simplifies the process but will hopefully give a basic understanding of the complex process that is archaeology.

As a researcher, I rely on the evidence gleaned by the excavators, and further added to by the various specialists: I work with archaeological reports, documentation and photos. But as a torc specialist I also work with the objects themselves and I am one specialist in the extensive network of artefact specialists that excavators, those writing up excavations and other specialists contact for further information. I am also regularly contacted by museum staff, Finds Liaison Officers and others working for the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

Context and torcs

Torcs are found buried and from this one simple fact we know that they must have been buried by people or by a process. To understand who buried them, how they were buried, why they were buried, when they were buried – or by what process – we need to understand the archaeological context of their burial.

Sadly, in most cases, we just do not have this information: of the 450 known torcs/torc pieces, only around sixty of them have been archaeologically excavated and those excavated torcs only come from one site: Snettisham in East Anglia. Of the remaining c.390 found across the UK, around 43 are antiquarian finds (I class antiquarian as being those torcs excavated by archaeologists or non-archaeologists, before the time when detailed archaeological context recording was established), around 20 were accidental finds during building works etc, but the majority – some 277 examples of complete/partial torcs or pieces of torc – are detected finds. The rest are torc pieces of uncertain provenance which come almost entirely from the unpublished Snettisham site.

The Snettisham site has produced around 370 pieces of torc, from at least 300 examples, of which c.63 are complete torcs (unfortunately, until the long-overdue Snettisham report is published the precise number is unknown: these estimates come from counting British Museum catalogue records).

The Snettisham site was excavated by the British Museum in the early 1990s under the direction of Dr. Ian Stead. However, the majority of finds from the site come from previous finds made from 1948 onwards, with Hoards A, B/C, D, E and F having been disturbed and removed either by the finder, or by metal detectorists, with no archaeological context recorded (this totals around 310 of the 370 torcs/torc pieces recovered from the site since 1948). In the case of Hoards B/C, discovered in 1948, we are not even sure which finds came from which hoard, and so both contexts are entirely muddled. These un-archaeologically excavated finds include the Snettisham Great torc, which was ploughed up by Tom Rout in 1950 (Fig. 3).

Beyond Snettisham, although excavations have occurred in the vicinity of several of the torc findspots (and sometimes fairly soon after the torcs were recovered) not one of the ninety plus other torcs we have – that were found in recent times by detectorists or in the past by antiquarians – from beyond Snettisham have been excavated in situ, by archaeologists. That includes the magnificent torcs from Leekfrith (Fig. 1), Blair Drummond, Netherurd, Newark, Alrewas and Clevedon. We only have accounts of the findings in some cases and often we have no idea if they were in situ or moved by a later process; buried in a pre-cut hole or natural hollow; exactly how far down they were buried; if there was any evidence of a container or wrapping for the torcs or if there was anything else buried with the torcs, which might not have been recognised by a non-archaeologist.

Often the torcs have been cleaned (usually washed; occasionally polished!!!) or – in the case of antiquarian finds – have often suffered re-shaping, repairs and treatments. As such, any traces of material within, or adhering to, the torcs have been lost (although not Iron Age, the 10th century Galloway Hoard Vessel is a superb example of how organics can survive, and be preserved, by careful archaeological excavation and conservation of a detected find).

In addition, thanks to the risk of illegal detector looting of any as yet undiscovered torcs at these sites, we often don’t even know, or are able to publish, where many of these torcs came from: this is why you will see torcs with vague names like ‘South West Norfolk’, or with ‘Area’ as part of a torc name. Not even I know the precise find spots of many. As such, thanks to antiquarians and detectorists, we have around 390 isolated torcs from across Britain: beautiful things but with no contextual information.

But this not a total disaster: as you will know if you have looked around the Big Book of Torcs, or leafed through the Further Reading pages on this site, there is a lot that has and continues to be written about torcs: their art, their craft and their distribution. But there is so much more I, and others, would like to write: about dating, precise deposition methods, locations and environments. Without more in-context, archaeologically recovered, torc finds this will always be impossible to do.

To show you exactly what I mean about what is possible in the research of archaeologically excavated finds, I want to share with you an example from the hoard site at Snettisham, Norfolk.

Hoard L from Snettisham, Norfolk

Despite the Snettisham site not yet being published, Ian Stead has been kind enough to send me details of the British Museum excavation and it is from these unpublished notes, and excavation photographs, that this account is based. The circumstance of this hoard find is a perfect example of a detector being used as a useful archaeological tool (the same as geophysics kit, etc) and of detectorists working successfully in close collaboration with archaeologists.

Hoard L was found by a detectorist working with the British Museum team in 1990. The hoard comprised twenty-one torcs, buried on the south side of the Snettisham gold field. Stead’s description from his notes is worth repeating in full:

“Found by [Tony] Pacitto with his metal detector, 6 December 1990. Initially Hoard L seemed to resemble the others excavated in 1990, an undisturbed ‘nest’ of seven torques (L1 – 7) buried about 0.1m below the level of the carrstone. But those torques were in the upper filling of a much larger pit, 0.45 by 0.35m across (0.36 by 0.27m at the bottom), and when they were removed the metal detector gave a loud signal.

Some 0.16 to 0.18m below L7 was the start of the most impressive collection found on these excavations, 14 torques [ L8 -21]in a pit 0.33m deep below the level of the carrstone. The upper torques had been deposited in sequence, L7 first and L1 last, but it was unclear whether they were in the filling of the main pit, contemporary with the lower torques, or had been subsequently inserted in a small pit cut into the filling of the main pit.”

The careful excavation of the hoard, the documentation of the pit/s, and the drawings and photographs (taken by the superb archaeological photographer, Dave Webb) allow us to reconstruct this feature in its entirety. Stead was uncertain if the torcs were found in one pit or two, but it is OK to be uncertain: he has raised the various possibilities and suggested that we might be looking at two temporal events, or a conscious decision to separate the upper (L1 to 7) and lower (L8 to 21) depositions during one phase of burial. The evidence could even suggest that older deposits were marked above ground in some way, allowing later depositions to be added to a closed, but marked, pit.

So thanks to Stead’s description, we now have several possibilities in mind when we look at other torc deposits from Snettisham, or from further afield: finding this arrangement at another site might suggest that this was a usual practice in Iron Age Britain. Or if we don’t find it again, this could suggest a practice local to the Snettisham area.

In addition, we have the precise order that the torcs were deposited in: L21 first with the first fourteen torcs carefully layered, one on top of the other, before there was a break in deposition, with additional soil lying between these torcs and the final seven torcs laid in the pit/s.

Photographs of the hoard in situ are incredible: we get a real sense of the event of deposition and how it must have looked to those present (Fig. 4). Even from just this one photo (which is one of many taken at each stage of the careful Hoard L excavation) we can almost see the people of the past placing those torcs in the hole, carefully overlaying them, one on top of the other.

But if I show you the Hoard L torcs from Figure 4 in the way I would get to see them (Fig. 5) without the descriptions or images we have thanks to their archaeological recovery – and with no idea about the pit they were deposited in, how they were deposited, and in what order – you would have no idea that they had been arranged as in Figure 4.

In addition, we know from the documented excavation, that torc L20 (Fig, 5, bottom middle), although broken, was deposited in the ground as if it was complete. This can tell us something about how torcs were regarded: that perhaps the history/story/essence of this torc meant it was valued, despite being broken and having lost its wearability.

Further finds from the pit, some tiny scraps of flat wire catalogued with the Grotesque torc (Fig. 6), along with other scraps in other hoards from Snettisham, have helped us to develop a theory that the Snettisham hoards were deposited in one event and we wrote about this in our paper ‘Thoughts on the Grotesque torc and the Snettisham (Ken Hill) hoards in the light of new research’. Without these teeny scraps, which would almost certainly have been disregarded by a non-archaeologist, we would have been unable to develop this idea, or write about its implications for other torc deposits from Snettisham.

Usefully, we also have organic material (lime bast and leather used to repair torcs, and wood contained within some neck rings) from other Snettisham hoard torcs and, thanks to the Dating Celtic Art project, from this material we now have calibrated radiocarbon dates for some of the torcs. Would we have had this material to be able to date it without expert archaeological excavation and conservation of these fragile organic materials?

In addition, having perhaps established that the torcs were all buried within a very short period of time, by looking at the order in which the torcs were deposited, a researcher like me can start to look at the style, decoration and technologies represented in the torcs and see whether the order of deposition can tell us anything about the torcs themselves: something I am currently working on suggests that they can.

I think Hoard L represents a buried lineage of torcs, the oldest at the bottom and the youngest at the top. The burial of this lineage of torcs – in order, but during one deposition event – might suggest the Snettisham hoards mark the ending of the age of torcs: curated and looked after torcs – that span a period of making and use over perhaps 300 years – deposited in a single event and removed from society forever. I will write more about this in due course but again, without the precise excavation data and recording, this research would not be possible. So much would have been lost.

The current state of play

Across the country, heritage is undervalued and underfunded. The current Treasure Act 1996 system of reporting and recording detected finds is overwhelmed as the detecting hobby becomes more popular and machines become more advanced and are able to be operated by even the least experienced user.

In England and Wales, finds are flooding the system. 53,490 finds were recorded in 2022 and 74,506 in 2023, bringing the Portable Antiquities Scheme database total to more than 1.7 million objects by March 2024. 1,358 of the finds in 2023/2024 were classed as Treasure. PAS staff, especially the Finds Liaison Officers, are overworked and under resourced. In addition, museums are having their budgets pared to the bone, with deep cuts being made to curatorial and specialist staff and, in some quarters, suggestions are even being made that collections should be sold off to balance the books.

We are also no longer looking at finds just coming from unstratified topsoil: time and time again across social media, images are being shared of disturbed in situ graves, hoards and other archaeological contexts. More often than not, such posts show finds that have been hauled out of their archaeological context without care: piles of metalwork, coins, dumped next to deep holes in the ground.

There are never photos of careful staged excavations, or finds recorded in place. Occasionally you will see flints or pottery, but these are rare and only those finds recognisable to the non-archaeologist will often be collected (we often talk of the paucity of non-metal finds from hoard contexts but in most situations currently, would we even know if they had been there or not?)

Money to acquire (‘acquire’ is a nice way of saying that museums – we the tax-paying public – buy the finds of lucky individual detectorists and landowners for our museums) is begged and borrowed from national funds and raised by public fundraising drives. The Treasure funds of museums are limited and the time and effort taken to apply for grants and to fundraise, by already overworked curatorial staff, is extensive. Treasure finds also need to be conserved and insured. These costs are covered by the museums.

Many museums just cannot afford to buy the increasing number of finds that they are presented with and some important and significant finds are declaimed and end up at auction, sold to the highest bidder and often removed from public view. In an increasing number of cases, individual detectorists and landowners get rich on the back of this heritage degradation: it is no wonder that increasingly detecting is becoming commercialised. Huge weekend rallies on archaeology-rich land now charge exorbitant fees in exchange for a cut of any Treasure find. Money is all.

This is not how it should be: these finds belong to all of us, as a nation. They are not ‘saved’ by individuals and they should not have to be bought from these same individuals, by us, for us. The records of non-Treasure finds (which are often returned to the finder) are, even with the diligent recording work carried out by the FLOs, not enough: in the case of torcs, I cannot tell anything about technology or making from a handful photos, and there will always be very specific measurements and data needed by me to be able to establish the precise method of manufacture. In short I, as a researcher, will always need to be able to look at an artefact if I am researching it as more than ‘just another piece of torc’ – and those artefacts just aren’t there for me to look at.

Yes, there have been incredibly important pieces of work and research carried out on material from the PAS database, but mostly these are distribution analyses or broader landscape studies: anything that requires you to get up close and personal with an artefact, or scientifically test it, is largely impossible. As such, technological studies – analyses of making – of the type I carry out on torcs are largely absent: they cannot happen with the data we currently have.

All the while we see archaeological artefacts as a monetised commodity this situation will continue: I work with gold all the time, I have handled more of it than most archaeologists will ever do but, in 40 years as a field archaeologist and finds specialist, I have never felt ownership over what I have found or worked with: sometimes I have dearly wished that I did own these things as they really can be covetable (it is always a trauma each time I put the Netherurd terminal back in its museum carrying case!). But ultimately, they are not mine: I just have the privilege to be in their space for a bit. To tell their story.

I think this is where archaeologists and a lot of detectorists differ (note that I do not say all detectorists: there are many detectorists and landowners, either working with the archaeological community or on their own, who share my feelings and who readily waive their ‘reward’ and donate to museums). I think we, as the archaeological profession, often recognise the value of knowledge over money: the fun is in the finding out and sharing, not in the acquisition.

Indeed, if you want a profession where wages are low – and where the bonus of a quick buck earnt from a nice find would be really appreciated – then archaeology is it. But we don’t: we dig things up and we hand them in (…and yes, before anyone howls, there have been, and always will be, a few archaeologists who steal from sites or museums, but they are genuinely few and far between: we wouldn’t have all the lovely material we do from excavations and in museums if everyone was thieving artefacts).

However, with an estimate of less than 10% of the 40,000 (some suggest 100,000) detectorists in the country recording (albeit that a large proportion of these may not be finding anything worthy of recording. But, then again, do they all know what in every case is – and isn’t – worth archaeologically recording?) there are, by this estimate, likely to be an awful lot of things being found which are not being declared. The ultimate of this is the illegal looters and so called ‘nighthawks’ who strip archaeological sites, often under cover of darkness.

Such activities happened at the Snettisham hoard site where ‘The Bowl Hoard’, probably the most important single Iron Age hoard ever found in Britain, was looted by detectorists in early 1991. Reportedly weighing more than it was possible to carry, in total the hoard comprised a silver bowl some 30cm by 20cm in size, filled with c.6600 coins, with at least ninety gold coins and a few ingots found below the bowl. Above the bowl were three brooches and a torc, or torc fragment.

Despite work by archaeologist Amanda Chadburn and others to locate and document the scattered hoard via auctions and private collections, its full extent remains unknown. I, and I am sure many other Iron Age specialists, have often thought of how much we could have achieved had we archaeologically excavated and recorded this hoard: how much data we would now have, the stories we could tell. Tantalisingly, the association of brooches (which are well dated for the Iron Age) and torcs could have helped to unlock the problems we have with the dating of torcs: if only we had the hoard!

Summary

I know not every archaeologist, detectorist or landowner will agree with everything I have written in this blog, but I think many will agree with most of it. The current situation is not sustainable and much is being lost from our shared national heritage.

If you are a detectorist, I would just ask that before you go out, before you dig, please familiarise yourself with the law and with good detecting practice and please, if in doubt, contact someone for advice. The details of the Finds Liaison Officers can be found here. Please remember that FLOs are ridiculously busy people so if they don’t respond immediately, don’t think this is your chance to DIY: these finds have survived underground for hundreds or thousands of years and they aren’t going anywhere in the next few days!

And please, if you do find Treasure, or it is found on your land, do consider a reduced reward, or think about donating the artefacts to a museum: they will be eternally grateful, as will researchers now and in the future. You will be doing a great thing for all in preserving your find in a public archive for everyone to appreciate for posterity.

Who knows, maybe you could even be the detectorist that I will be singing about from the roof tops as the one to facilitate the first archaeological excavation and recording of a torc in over 30 years: now that really would be a thing to show off on social media about. Imagine the stories we could tell!

As I always say, it really is good to torc!

If you are interested in learning more about archaeology, do think about joining the Council for British Archaeology or getting involved with your local archaeological society. If you have youngsters who are interested, then the Young Archaeologists’ Club may be for them. If you are thinking of studying archaeology at university, University Archaeology UK has more information. Many museums around the country offer archaeological events and finds days: do check them out.

15 Replies to “Detecting and torcs: a researcher’s view.”