by Tess Machling & Giovanna Fregni

[A download/print PDF version can be found at the end of the paper]

This paper can be cited as: DOI 10.5281/zenodo.13911434

Abstract

In September 2024 a paper, ‘The Pulborough gold torc: a 4th to 3rd century BCE artefact of European significance’ was published by a British Museum team in the online journal Internet Archaeology (Adams et al 2024). This paper was a response to our earlier paper ‘‘All the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order’: The riddle of the ‘Pulborough Area’ torc from Sussex.’ (Machling et al 2023).

The Adams et al paper claims to have ‘refuted’ (Adams et al 2024, 2. Discovery) our claim that the torc was of early 20th century manufacture, and further suggests that ‘Pulborough can be added to a small but growing group of mid- to late first millennium BCE gold items of personal adornment found in England’ (Adams et al 2024, 7. Conclusion).

However, we believe that the confidence of the British Museum team in ascribing a definite Iron Age date to the torc is undermined by significant flaws and/or omissions in their research. In addition, even if one accepts an Iron Age date for this artefact, the absence of acknowledgement by Adams et al that a suspected forger and planter of archaeological artefacts (Machling & Frieman 2024) was depositing material within yards of the Pulborough torc findspot (Machling et al 2023, 29) raises further questions which need to be addressed before a secure in situ Iron Age provenance can be ascribed to the torc.

This paper will highlight areas where we feel further research still needs to be undertaken and will correct the record regarding various issues raised by Adams et al. However, as we said in our 2023 paper, ‘unless further work identifies a ‘smoking gun’ of evidence, it is likely we will never know for sure’ (Machling et al 2023, 30) whether the torc is an in situ Iron Age find, a planted Iron Age find or a forgery.

As the evidence stands, we believe all three scenarios are still possible and that the overall thesis of our paper is still justified. As such, the arguments made in our 2023 paper will not be repeated here and can be read and evaluated in the original text. But when we are wrong we are not afraid to admit it (for example, see here) and in this paper we will correct the record concerning an error we made in our 2023 paper, by ascribing an incorrect diameter to the original, if complete, torc. That is probably a good place to begin.

The diameter of the ‘Pulborough Area’ torc.

In measuring the diameter of the ‘Pulborough Area’ torc, we (TM) used a pottery rim chart to measure the remaining undistorted section (what Adams et al refer to as Part B) of the broken neck ring (Machling et al 2023, Fig.3). We have since become aware that – due to confusion between two rim measuring charts, one that had diameter measurements shown and another showing radius measurements – we overestimated the diameter of the putative complete torc by a factor of two. Therefore the original torc, if complete, was likely to have been at least 100mm in diameter, and we would agree with Adams et al’s suggestion of a torc neck ring diameter of ‘150mm or more’ (Adams et al 2024, 3. Shape of the torc).

Metal composition

The Adams et al paper describes a set of XRF composition analyses carried out in both 2020 and 2021. No detail is given as to the precise location of the 2020 readings, which are described as ‘various’ (Adams et al 2024, 3. Shape of the torc). In 2021, three readings were taken in recorded locations from Part A of the torc (Adams et al 2024, Table 1). However, no readings were taken from Part B of the torc, or on the ‘cast’ disc closing the terminal cone, despite this apparently being of a different manufacturing method to the rest of the sheet-made torc. Only one reading was taken on the wires, and that on only one of the many wires attached to Part A of the torc. Although the solder was apparently analysed, no detail is given, only that the solder composition did not contain ‘any elements that can be found in some more recent gold solders, such as cadmium and zinc’ (Adams et al 2024, 3. Shape of the torc).

As things stand (Table 1), we have no data regarding the composition of the majority of the sixteen-plus individual components that have been joined in the making of this torc, and no data regarding the precise composition of the solder in any location. In such a contentious artefact, best practice would suggest multiple readings from each component are necessary, as detailed in Table 1.

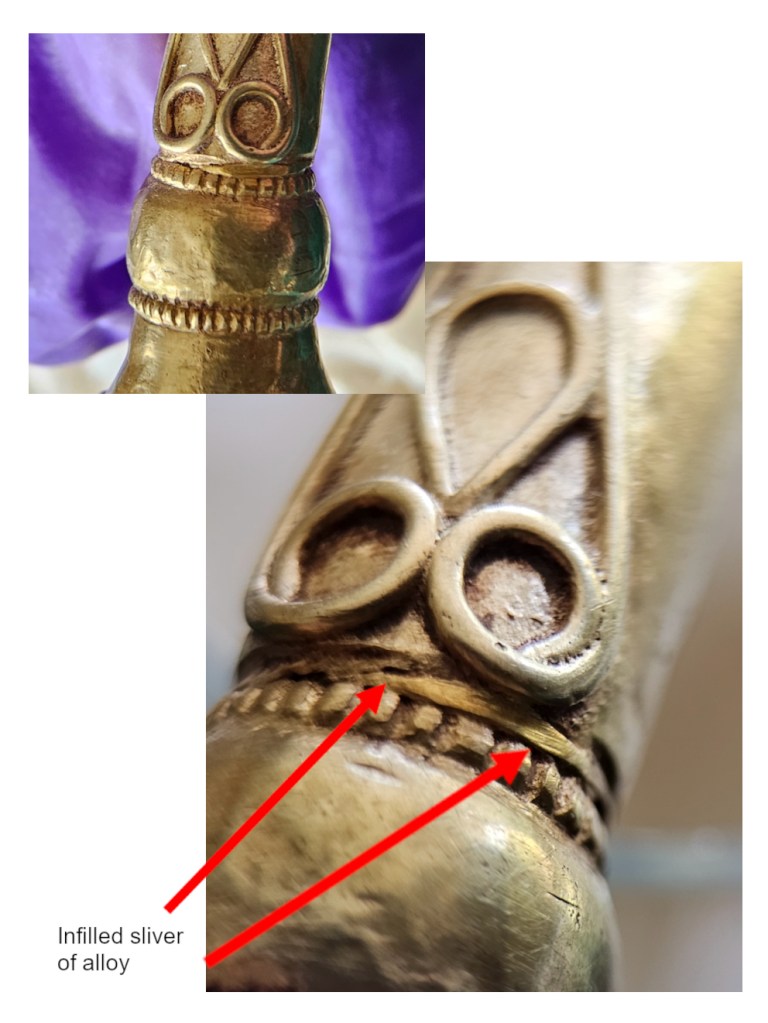

In addition, as described in our 2023 paper – but apparently unrecognised by the British Museum team – there appears to be a sliver of infilled gold alloy between the collar and neck ring (Fig. 1 & Machling et al 2023, Fig. 21, top middle; and clearly visible in Adams et al 2024, Figs. 2.2 and 3.1) which seems to be of a different colour to the rest of the torc and which appears to post-date the compiling of the torc body as it overlays the chiselled false-beading, and yet underlays the applied wire. The difference in colour suggests that it might be of a different alloy composition. This would be an important feature to analyse with XRF.

We would therefore argue that, in light of the absence of comprehensive XRF analyses of the multiple components of the torc, it is difficult to ascribe certainty in the gold alloy composition across the torc.

Iron Age coins

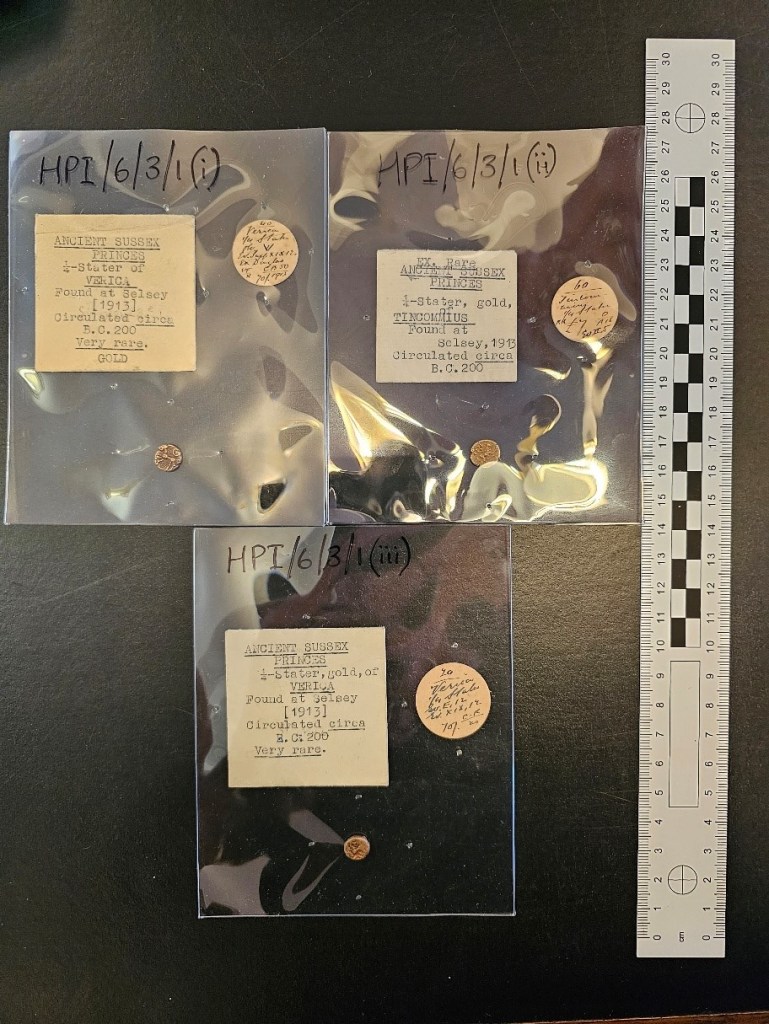

As detailed in our paper (Machling et al 2023, 28), Harry Price was in possession of fifteen Iron Age gold coins, which were apparently stolen in 1923. Three gold coins remain in the Harry Price archive (held at Senate House Library) and can be matched to examples given in Harry’s report to the Metropolitan Police (HPA/4/7; Machling et al 2023,Fig. 41). Since publication of our paper, TM has seen these three remaining coins (Fig. 2).

The typed notes and hand written labels included with each coin (written by Harry Price), confirm that all three coins were found in 1913, and so their ownership by Price predates the loss of coins in 1923. Harry’s assertion that he ‘had a fine and rare collection of the ancient gold coins of the Sussex princes…stolen from Pulborough church. The coins included those of Tincommius, Verica, and others. Some were unique…’ (Price 1942, 51) suggests strongly that these coins were part of that stolen collection. We would again draw the reader’s attention to the likely weight of the stolen coins: between 50.5g-70.5g, the weight of the ‘Pulborough Area’ torc being 57.54g (Machling et al 2023, 28).

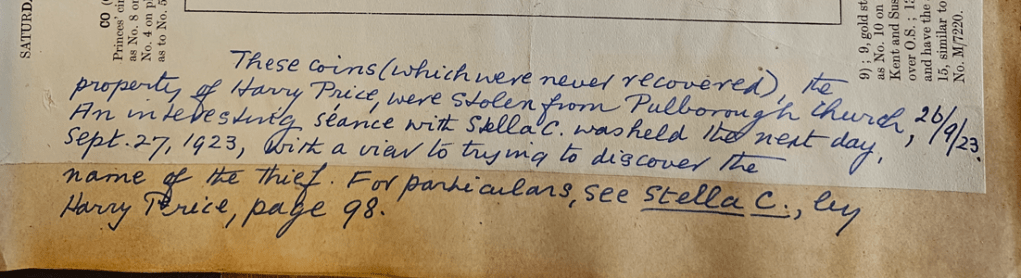

On 27th September 1923 – the day after the theft of the coins – Harry Price held a séance to uncover the thief (Fig. 3). The proceedings of the séance are recorded in the American Society for Psychical Research journal: ‘Mr. Price then asked “Palma” [Stella Cranshaw’s psychic voice] if she could give the name of the thief who had the previous day stolen his gold coins. The answer was rapped out: DINGWALL KNOWS HIDE I DON’T. This answer was not taken seriously.’ (Price 1924, 360).

Stella Cranshaw was a very close associate of Price and one of his trusted mediums, and Eric Dingwall – an infamous ‘anthropologist’ – was also a close collaborator. With the séance featuring such close confidents as Cranshaw and Dingwall – and with a very typical ‘Harry style’ hint of what had been done – there is a possible clue how the theft was achieved, although this can probably never be proved.

In the Adams et al paper there is no mention of the possibility raised in our paper that the torc was made from melted down Iron Age coins, the source of which could be the stolen coins from 1923. Instead, the Adams et al paper focusses on the similarity of the torc alloy composition to that of a number of other torc examples. However, in an earlier paper two of the Adams et al paper authors recognise that ‘it is presumed that recycled continental coinage provided the gold and silver used by goldsmiths’ (La Niece et al 2018, 407) and so it is surprising that they do not at least acknowledge the possibility that the making of the torc in genuine, albeit later curated, Iron Age coins could have occurred.

Had this happened, it would be impossible to detect from alloy composition analyses, or by comparison with other Iron Age torc alloy compositions – which would be similar to those seen on the Pulborough example. As such the ‘Contra Machling et al 2023, 19’ (Adams et al 2024, 4. Metal Composition) does not stand scrutiny, particularly as we pointed out that ‘the copper amounts within the ‘Pulborough Area’ alloy are more suited to an Iron Age composition’ (Machling et al 2023, 19).

Sheet thickness

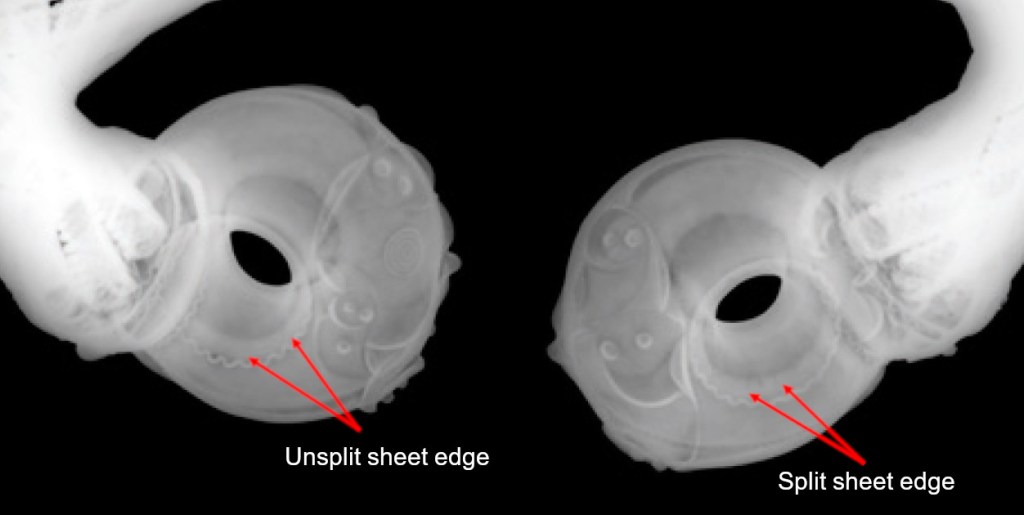

The sheet thickness measurement of 0.18-0.22mm given in the Adams et al paper (Adams et al 2024, 5.1. The hollow neck ring) is misleading (Adams et al 2024, Fig. 5.3). This measurement appears to have been taken on one of the split seams of the torc neck ring and has measured only the sheet thickness at its thinnest where the sheet edge tapers so that the two thin sheets can be overlapped and bonded. That the neck ring sheet is overlapped, rather than butted, can be seen in their Figure 5.2a. In their Figure 13.1d the full thickness of the neck ring sheet can be seen to be comparable to our measured 0.4mm (Machling et al 2023, 3).

Design and manufacture

We remain open to the possibility that the terminal of the torc is not made of sheet gold, but instead cast, with various irregularities in the collar and terminal surface, and difficulty of forming the thistle-shape in sheet (all Iron Age examples in hollow gold of this terminal form, such as those from Waldalgesheim and Filottrano are hollow cast) suggesting that the terminal could have been cast, hammered and cut to fit (hence the seam).

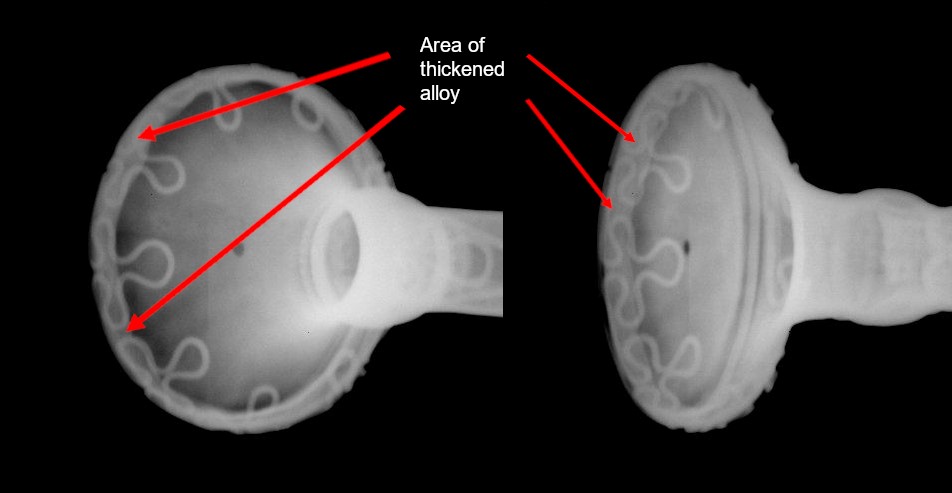

The disc interpretation for the piece of material closing the terminal (Adams et al 2024, 5.3. The buffer terminal) is also contested and we would still suggest that the disc is in fact a ‘bottle top’ shaped cap: the x-rays within the Adams et al paper apparently show a circumference band of thicker alloy within the torc terminal (Fig. 4) which is not explained within their text and which would support the closing cap interpretation, the side of the cap causing a double layer of alloy thickness around the inner circumference of the ‘trumpet’ end.

From the x-rays of the ‘Pulborough Area’ torc, the splayed collet within the collar cannot be compared with that of the Snettisham Great torc (Fig. 5). In the case of the Snettisham Great torc, the splits are ragged and haphazard and can only be seen on one of the two terminals, suggesting that it was not a manufacturing feature, but more incidental as a cracked and overworked sheet margin (Machling & Williamson 2023, 9). The x-ray images of the Pulborough torc collar show a very intentional cutting and splaying of the collet (Adams et al 2024, Figs. 7.2a & 7.3), the Snettisham Great torc does not.

Block-twist wire

In the new paper (Adams et al 2024, 5.4. Filigree) there is a misreporting of our reasoning regarding the block-twist wires of the torc. We welcome the correction by the paper authors of their previous mis-identification of the wires as having been strip-twisted, but there is no need for the ‘Contra Machling et al 2023’ (Adams et al 2024, 5.4. Filigree) as there is nothing that was said in our paper, that they have not said in theirs.

There is also a misunderstanding of block-twist wires, with the Blair Drummond wire torc described as having been made from ‘block-twisted wire’ (Adams et al 2024, 4. Metal composition). This is misleading as the Blair Drummond wire torc, and others – such as the Snettisham Grotesque torc (British Museum Catalogue: 1991,0407.37 and 1991,0501.157; 1991,0501.190; 1991,0407.33, etc) – has wires which can better be described as twisted, square cross-section wire, rather than fully achieved round wire created using the block-twisting technique. The fully achieved, rounded, block-twist wire of the ‘Pulborough Area’ torc has not been identified in any other Iron Age torc yet found from Britain and Ireland.

Adams et al’s noting of the description of the method of block-twisted wire in the 1930s by Herbert Maryon (Adams et al 2024, 5.4. Filigree) still leaves open the possibility of a faked torc using block-twisted wires if we accept that the likely dates for a Harry Price instigated forgery would be between the theft of the coins in September 1923 and Harry’s sudden death in Pulborough in March 1948.

A further misunderstanding of our paper in this same section (Adams et al 2024, 5.4. Filigree) suggests that we have said that 19th century examples were created with block-twisted wire. Our words,

‘Many of Castellani’s replicas/forgeries were only uncovered due to his use of drawn, rather than ‘strip twisted’, wire (Meeks 1998). However, … the knowledge that Berthelot appears to have recognized – and wrote about – the ‘strip twist’ wire technique in the later 19th century suggests that there may be other replica/forgery makers out there who might be less easy to unmask using this technique’,

clearly show that we acknowledge that drawing was the normal method of wire production in the 19th century but that, should strip/block-twist wire be proved to be earlier, this method might not be an effective method of uncovering forgery. We stand by that suggestion.

We would also question the assertion that 19th/20th century Revival copies do not ‘bear the simple loose sinuous filigree designs of the Pulborough torc’ (Adams et al 2024, 5.4. Filigree) when items of Castellani altered (British Museum catalogue: 1872,0604.747), created (British Museum catalogue: 1872,0604.179; 1978,1002.734) or other 19th/20th century forged items of jewellery (British Museum catalogue: 1930,1106.1-2) which show such filigree can be easily found, even in the British Museum collections. As such, block-twist wire – a known method within the time frame of the activities of Harry Price – cannot be used to definitively rule out the ‘Pulborough Area’ torc as a forgery.

Solder

As previously discussed, the solder used on the torc is poorly applied and flooded the surface of the torc. In the Adams et al paper, the solder is ruled out as being modern thanks to an absence of modern elements and a similarity to the gold alloy in the torc. But, without detailed XRF readings on the solder, this interpretation cannot be confirmed.

In addition, the dismissal of the solder being modern due to the ‘different appearance compared to the ‘modern’ soldering method of using snipped pieces of strip solder or pallions’ (Adams et al 2024, 5.5. Solder) ignores the possibility that wires were attached to the terminal and neck ring using poorly achieved sweat-soldering, where solder is applied to one side of a piece of metal prior to attachment (Untracht 2011, 416).

The solder flooding over the metal surface could have been caused by an inexpert application of heat, or the use of a single type of solder that would repeatedly melt when multiple applications of decoration were applied. Another observation is what appears to be an attempt to fill gaps between the wire and metal by inserting additional small pieces of gold (Fig. 6).

Additional chemical analyses of the solder would be beneficial to learn if different types of solder were used to attach the decoration. Some of the wire decoration is round, leaving scant areas for surface contact for soldering. Examples of similar decoration on other torcs (for example, possibly the Leekfrith bracelet) have wires that appear to have been flattened on the bottom, thus ensuring a flush surface with a larger contact area to connect to the metal surface below. If it was a more recent forgery, we should not forget that whoever made it was not necessarily a proficient goldsmith and so unusual features may be seen that do not correspond to traditional goldsmithing techniques.

Design of the decoration

Two examples of filigree work from the Adams et al paper were previously unknown to us (Fig. 7) and make a compelling case for the credibility of the ‘Pulborough Area’ torc as Iron Age: the Dornburg-Wilsenroth decorated tube fragment (Hansen 2007) and the Veringenstadt ring (Schönfelder 2003). These examples show compatibility with the decoration seen on the ‘Pulborough Area’ torc.

However, although comparable, the small size of the Dornburg-Wilsenroth tube – at only 5mm in diameter – means less detailed wirework would be expected. In addition, a similarity of design would not be surprising if someone in the 20th century was trying to copy the relief designs of a torc like Waldalgesheim in wire. Similarities will be seen in both Iron Age styles and modern Iron Age styled forgeries. Again, similar designs in wire can be seen in the Revival pieces shown in our original paper (Machling et al 2023, Fig. 23).

Wear and damage

Wear, scratches and damage are not unique to ancient finds. The late 19th/early 20th century Belgian torc in the British Museum collections (British Museum Catalogue 1930,0411.1), until relatively recently assumed to be authentic, shows extensive evidence of such wear and damage (Fig. 8).

Although wear can be seen on the side of the Pulborough terminal, the proximity of this ‘wear’ to the extensive abrasion of the face of the terminal (an area where normal use-wear would not be expected, and which cannot be adequately explained as contemporary wear or finishing) raises doubts about any wear on the torc being consistent with use.

The poor condition of the gold seen in Adams et al 2024, Figs. 14.2c-e would not be unexpected in a badly achieved alloy of Iron Age gold coins. In addition, having been buried in boggy ground for over 100 years, it would be expected that certain adhesions and scrapes would be received by the torc in that time, particularly if the ground was ploughed etc. The modern scrapes, as a likely product of recent excavation, offer no evidence as to the torc’s antiquity.

Context

The most surprising aspect of the Adams et al paper is the absence of recognition of Harry Price as a potential agent in the torc’s object biography. The finding of the torc within 500m of two other known Harry Price forgeries (the inscribed bone and silver ingot), and the evidence that Harry not only forged finds but also planted genuine artefacts (Machling & Frieman 2024) should not be ignored. Even if we accept the torc as a genuine Iron Age French/German inspired example made by goldworkers in these islands or as a European original imported here, the well documented activities of Harry Price make it more than a possibility that the torc was planted.

The Adams et al paper ignores this evidence and instead postulates various Iron Age scenarios for the movement of the torc:

‘The location of this find, towards the south coast of England along ancient routes of Atlantic and cross-channel contact and trade, is intriguing given the disparate influences seen in the design.’ (Adams et al 2024, Summary).

‘It is tempting to consider the possibility that material and techniques moved along the Atlantic coast at this time, resulting in the distinctive torc type turning up in the southern coastal region of England in a location reachable by boat from the coast.’ (Adams et al 2024, 4. Metal Composition).

At no point do the authors consider that the torc might have been purchased from a ‘modern’ foreign source (Price often frequented France and Germany) and then brought to Pulborough and planted.

Conclusion

The ‘Pulborough Area’ torc is an enigma. A continental inspired design (and yet crudely executed) the torc was at some point buried in a field in Pulborough, West Sussex. There are three options for the deposition of this torc: that it is a forgery made or commissioned by Harry Price, that it is a genuine Iron Age artefact planted by Harry Price, or that it is an Iron Age torc deposited over 2000 years ago.

We believe that any of these three options remains possible and that there is still currently not enough evidence to definitively prove, or disprove, any of these scenarios. As such, contra Adams et al 2024, we believe the jury is still out. What we can be pretty certain of is that, if Harry Price could see all this, he’d think it was wonderful.

References:

Adams, S., Craddock, P., Hook, D., La Niece, S., Meeks, N., O’Flynn, D. and Perucchetti, L. 2024 The Pulborough Gold Torc: a 4th to 3rd century BCE artefact of European significance, Internet Archaeology 67. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.67.16

Flynn, D. 2017. X-ray imaging of the Snettisham Great Torc. British Museum Scientific Research Newsletter, 3. 1.

Hansen, L. 2007 ‘Ein Frühlatènezeitliches Goldhalsringfragment Von Dornburg-Wilsenroth (Kr. Limburg-Weilburg)’, Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt 37(2), 233-46.

Machling, T & Frieman, C. 2024. The Springhead Clump lanceolate flint dagger from Parham, Sussex: a genuine find or a planted object? PAST: The Newsletter of the Prehistoric Society 107 (Summer 2024), 12–14.

Machling, T & Williamson, R. 2023. The sheet torus torcs from Britain: an update. DOI 10.5281/zenodo.10511424

Machling, T, Williamson, R & Fregni, G. 2023. ‘All the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order’: The riddle of the ‘Pulborough Area’ torc from Sussex. DOI 10.5281/zenodo.10511405

Price, H.1924. Stella C – A Record of Thirteen Sittings for Thermo-Psychic and Other Experiments. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research. 8, 5. 305-362.

Price, H. 1942. Search for Truth: My Life for Psychical Research. Collins, London

Schönfelder, M. 2003 ‘Eind Goldener Fingerring der Fruhlatenezeitaus Veringgenstadt, K.R. Sigmaringen’, Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt 33, 363-74.

Untracht, O. 2011. Jewellery concepts and technology. Robert Hale, London.

One Reply to “”