by Tess Machling

[A download/print PDF version can be found at the end of the paper]

Introduction

The recently published Snettisham hoard volumes are long awaited, and contain much that is of use and interest to anyone studying Iron Age Britain. However, as a gold researcher, working with a team of goldsmiths, silversmiths, jewellers and metalworkers, there is a significant amount of interpretation in these volumes that cannot be evidentially supported.

There are a number of fundamental errors which show a basic lack of gold and metal working knowledge. Citations do not have page numbers and there are examples which, when checked, do not back up what is being said in the text. There are confused areas of text and basic metrics are missing. There are also a number of occasions when mine and Roland’s published – peer reviewed – research into the technology and manufacture of torcs is either ignored, claimed as being ideas of the British Museum team, misreported or misunderstood.

Before anyone says it, yes, we’ve all had pieces of writing where, despite hours and hours of editing, proof reading and checking we find glaring errors that we only see when the publication lands on our desks, fully formed and uneditable. But this is not that. This is a wide ranging suite of errors that should have been spotted and corrected, either during writing, editing, proofing or peer review. Many should not have been written in the first place. Any publication from the British Museum will be deemed to be learned and ‘of record’: that the sections of these volumes which refer to the torcs contain multiple errors of fact, or omission, is a concern. This article places my concerns on record.

Inevitably, as one of only a very few researchers working on the gold Iron Age torcs of Britain, much of what I refer to will be mine – and Roland Williamson’s – research. This is not a situation I feel entirely comfortable with. However, this research is not just the product of one or two minds: my research utilises the knowledge and understanding of a wide range of trained and experienced goldsmiths, silversmiths and jewellers and thoughts from additional craftspeople I have talked to over the last few weeks are incorporated here also.

Throughout this piece I will refer to torc and/or page numbers as given in the Snettisham volumes: these volumes can be downloaded for free from here and I would encourage you to check my work. As ever, I hold that all research should be transparent and open access, and any reader should be able to examine any and all the evidence for themselves and be able to discuss it with the author. So please do drill down into what I’m saying and if you’ve got any thoughts or questions, I’m always happy to talk. My contact details are here.

The Snettisham Volumes

The Snettisham volumes are a two-volume work of 728 pages and 400 illustrations. The books include a huge amount of information on the archaeology of the site and the finds that have been uncovered since Ray Williamson first ploughed up the torcs in 1948. Much of the information is relevant, well researched and evidentially supported.

There are many fascinating insights: for me, of particular interest was the geophysics findings of rectilinear enclosures (p. 46), the Hoard F helmet (p. 266) and the possible torc maker identified through a specific style of torc and manufacturing technique (p. 512). The Catalogue of finds (p. 115) is an essential resource and the Gazetteer of British torcs (p. 570) will be useful for anyone not aware of the range of torcs that have been found in these islands. The illustrations by Jim Farrant and Craig Williams are stunning throughout and add much detail which would not be obvious from photos alone. In addition, the suite of iconic, in situ, hoard photographs by Dave Webb are utterly wonderful.

Errors and omissions.

Although the errors and omissions in the Snettisham volumes appear at first minor and insignificant, for any scholars of torcs or Iron Age gold, they will allow for misunderstanding, and a replication of errors in future studies. These errors are not points of view nor academic disagreements: they are the omission, distortion or misinterpretation of significant amounts of important information as regards the Snettisham torcs – and other comparable finds – and show either the intentional exclusion, or lack of awareness, of the corpus of torc research to date. I’ve split the following into two sections: general problems I have noticed and, secondly, those that relate more specifically to certain torcs.

i) General

Chapter 13 details the typology of the torcs and offers a much needed standardized terminology for torcs, which builds upon – though does not acknowledge – our previous work. The naming of ‘torus torcs’ was first given by us in 2016 (for example, Machling & Williamson 2016, 2018 & 2020, Fig. 3).

One confusing section (p. 148-149) mixes ‘diameter’ and ‘circumference’ throughout the text (and in Fig 13.1): it is unclear which is meant. However, from my knowledge of the torcs, the measurements given are likely to be circumferences. But it is also not clear if the ‘circumference’ measurement (if that is indeed what it is) includes the variable gap between the terminals of flexible penannular torcs: I would have preferred to see internal and external diameter approximations, as in the catalogue (p. 115).

In addition, the omission of a circumference measurement for bracelet E.1c, (Fig. a) the one ‘complete circle’ artefact from the entire site and where – despite the distortion of the artefact – an accurate circumference measurement would be possible, is a curious absence.

In Chapter 22, p. 558, the understanding that ‘the ring terminal from Netherurd may also have never been joined to a neck ring’ is attributed to our 2018 PPS paper (Machling & Williamson 2018). However, within this paper, what we actually said was that ‘although the Netherurd terminal is now detached, small dents on the top, legacy wire marks, and residual solder from the terminal attachment attest to it having been part of a complete torc. Indents in the opening are evidence that it was probably attached to a neck ring of eight or nine (Clarke 1951, 60) wire ‘coils’. (Machling & Williamson 2018, 390). As such this is an entirely wrong reading of our work: the Netherurd terminal was certainly once attached to a neck ring.

Throughout the two volumes, mention is made of six of our papers ranging in date from 2016 to 2024 (see p. 685). However, notable by their omission are several other papers: Machling & Williamson 2019, 2020a, 2020b 2021, 2023a & 2023b; Machling et al 2019 & 2023 and Machling 2022. This is significant as several of these papers detail evidenced manufacturing theories which have not been acknowledged or addressed in the volumes. The inclusion of several of our papers from 2016 to 2024, but the omission of a significant number of equally relevant peer reviewed journal articles, book chapters – or evidenced – papers from this same period of time is suspicious.

There are several original ideas – for example, the sheet manufacture identification of Torc F.74 (Machling & Williamson 2020, 87), work on the Newark torc (Machling & Williamson 2020a, which includes high quality, 450kV, x-rays of this torc as opposed to the poor quality x-rays of p. 471-2 ) and our published theories regarding torc manufacture and dating (Machling 2022, Machling & Williamson 2019, 2020, 2021, 2023a and 2023b) – which have been entirely ignored in the text or which, although we published these ideas first, have become subsumed, unacknowledged, into the British Museum narrative. A mention of the British Museum ‘Pulborough Area’ torc paper (Adams et al 2024) has also been made (p. 551) with no balancing reference to this torc’s contentious biography/findspot (Machling et al 2023c).

In the case of the ‘Near Stowmarket’ torc – named the ‘Great Finborough’ torc by the British Museum – our 2020 paper on this torc (Machling & Williamson 2020b) is not referred to anywhere in the volumes. As such, the two names and omitted research will cause confusion for future scholars. In addition, the current location of the torc has been incorrectly listed as ‘unknown’ (p.580), when it remains in the possession of the finder, whose identity is known both to us and Suffolk Archaeological Service.

ii) The torcs

Chapter 14 is the meat of the volumes: the catalogue of hoards and other metalwork. The finds are organized by hoard, with an additional section of non-hoard metalwork finds. Each find has an alphanumeric entry which refers to the hoard it came from (or an S-number for finds without context) and includes measurements, weights and classifications. Sadly, there are only a very few measurements given for the wall thickness of the terminals – even where x-ray data was available, or calliper measurement possible. This data is crucial for anyone looking at metalworking technologies of the past and, in such objects which cannot be easily examined by researchers, is a notable lack. By not having this information, many of the theories of torc terminal manufacture posited later in Chapter 17 (p. 464-475) cannot be interrogated or validated.

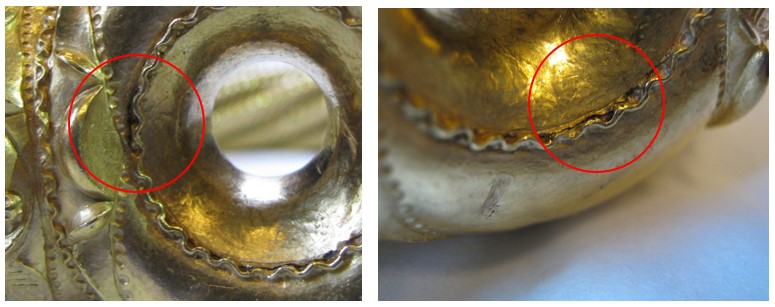

In addition, there are ‘Notes from scientific analysis’ by Nigel Meeks included with certain finds. However, within these notes, there are a number of errors and confusions with, for example, torc terminal manufacturing technology being misidentified. Torc L.14 is described as having terminals which were cast separately, and perhaps secured with rivets. However, the British Museum catalogue images for Torc L.14 under 1991,0407.32 clearly show (Fig. b) the break through wires and tell-tale signs of a failed cast-on terminal, rather than a ‘hollow casting attached to the prepared wires of the neck ring’ (p. 301).

I am also suspicious – although uncertain – of the interpretation of the terminal of torc L.16 (p.303) which would appear to show overcast, or additional material, with an imperfect bond, similar to that seen in the Needwood Forest torc, although less pronounced on that torc (Machling 2024, Fig. 6), rather than sheet wrapped over the wires. In addition, throughout the ‘notes’ there are photo images which are unclear as to the information being shown (see Fig. 14.6) or which have been presented without scales or measurements (Figs. 14 onwards).

It should also be noted that the use of European goldsmithing terminology (p.425), where research has shown that this is not always applicable (Machling et al 2019) reinforces colonial, Western focused, ideas of gold working, for which there is limited proof in prehistory. For example, the unexpected ‘mottled texture’ seen in torc A.6 (p.168) can be straightforwardly explained if the torc was worked from the exterior using a method akin to the Japanese uchidashi technique. This technique has been shown to have been used in other examples of sheet gold work (Machling & Williamson 2020a, 91; 2020b, Machling et al 2019) but is unreferenced within the volumes.

Within the catalogue, a piece of gold ribbon (F.67) does not appear to have been recognized as what could be an untwisted example of a – specifically – Bronze Age ribbon torc (Hunter 2018, 432). If Bronze Age, rather than Iron Age (suggested by the simple twist of a plain ribbon of gold, rather than the complicated hammered manufacture seen in Iron Age examples) this is an important find. Its inclusion within the sealed Hoard F is worthy of further discussion, which does not occur.

Technology and manufacture & the Snettisham Great torc

Chapter 17, which deals with the technology and manufacture of the torcs is – as a gold researcher who looks at torcs from a craft perspective and works with a team of goldsmiths – often a hard one to read. However, there are positives: the section about wires is comprehensive and well achieved, marrying scientific examination with experimental work by John Fenn, a practicing metalsmith. The insights from this dual approach have created some fascinating results which tie the evidence seen on the wires to how they might have been produced and the time it might have taken to produce them.

However, for the examination of the terminals and other metalwork (from p. 457 onwards), omitting the insights of goldsmiths has led to some evidentially unsupportable conclusions (see, for example, torc L.14 above).

The most glaring error occurs with the ‘iconic’ Great torc which is incorrectly identified as being of sheet and cast hybrid construction. The multiple evidence seen on the Great torc (dents, cracks and hammering), comparable examples (for example, the Netherurd and Near Stowmarket terminals), and previous research (for example, that by Maching & Williamson, see References) which supports the interpretation of the Great torc terminals having been created using only gold sheet, has been largely ignored.

It is at this point that the knowledge of goldsmiths is integral: even with modern vacuum and centrifugal casting methods, creating a successful hollow cast with multiple 3D relief elements and a wall thickness of less than c.1.5mm is extremely difficult. In other cast terminal torcs (for example, the Newark torc) a wall thickness of between 1.6 and 2.2mm has been recorded.

Although no terminal wall thicknesses are given for the Great torc, measurements I have taken from Fig. 17.93, which apparently shows ‘the thickness of the gold at this point’ (p. 469) suggest a wall thickness of c.0.2mm: an extremely thin – and likely wrong – gold thickness much less than the c.0.7mm seen in other sheet torus torcs of this type. This thin measurement could, however, be explained by the thinning of the gold at the sheet edge overlap between the terminal shell and collar. But to have achieved this thinness of cast in the Iron Age, as is stated by the Science team, would have been impossible. It can only be sheet gold.

In addition, the tiny, single, ‘dendritic cold-shut casting feature’ (p. 469) used as supporting evidence for a cast terminal shell shows a lack of gold working knowledge: such ‘cast’ features can easily transfer from an original – cast – ingot when it is hammered into sheet. That such porosities can survive the hammering process is admitted by the science team for torcs F.135 and F.156 where ‘unexpected’ ‘residual cast dendritic microstructures’ were seen in 1.8mm and 1.3mm diameter wires despite ‘the extensive hammering thought to be necessary in preparing them’ (p. 431).

The ‘shrinkage crack’ (p.469) seen in the valley between the Great torc collar and torus shell is also easily explained as this is the site of a sheet overlap join (between the collar and torus shell) which would be vulnerable to stress. A similar crack can be seen on the face of the Great torc (Fig. c) where the core sheet edge (note: this is not an ‘applied’ and ‘soldered’ (p. 467) feature. This is demonstrated by x-ray Fig. 17.95, which shows the wavy line to be part of the sheet core) is parting from the terminal shell (Machling & Williamson 2023b, Fig.16). A thickened area of alloy where the sheets of the torus and collar likely overlap can be seen in the x-rays of Fig. 17.84a, again suggesting that, like the torus shell/core boundary the torus shell and collar were separate sheets which were then overlapped and joined.

On p.468, no acknowledgment is given to the likelihood that the Great torc has ill-fitting terminals, which were almost certainly repaired at a later date (see Machling & Williamson 2019 & Machling 2022): a theory that would explain the insecure fitting terminals and the flooded metal on the collar/wire attachment.

The convoluted – and unevidenced – explanation given on p. 469 of the process of casting, raising and punch-moulding the 3D terminal elements is highly improbable and not supported by evidence from either the Great torc or any other torc. There is no evidence of casting and I am entirely unsure where the idea that anything of the decoration of the Great torc could have been ‘punched into moulds’ (p. 469) could have come from: even a cursory glance at the terminals shows the absence of anything that could resemble evidence of moulding.

The Great torc terminal has been previously shown to have been made from sheet gold alloy, likely using a mixture of exterior and interior working (Machling & Williamson 2018, 2019, 2020 & 2023b). This is confirmed by a number of goldsmiths who ‘can’t believe anyone ever thought that these weren’t made from sheet’ (Machling & Williamson 2019, 184). There is no evidence given in the current work which disproves this.

The section on p.471, comparing the x-rays of the Great torc, the Snettisham Grotesque torc and the Sedgeford torc is also unindicative: the small image in Fig. 17.101 does not show a significant difference between the wall thicknesses of the Great and Grotesque torcs, with only the Sedgeford torc standing out as different, and thicker. In particular, the Snettisham Great torc x-rays in Figs. 17.82, 17.83 and 17.84a & b show no significant difference between the terminal thicknesses of the torus shell and core. As such there is no evidence from the Great torc x-rays that the Great torc shell was cast, but much to suggest it was sheet gold.

Alloy composition

Unfortunately, alloy composition measurements are only available for samples from Hoards A, B, C and F. All these hoards are unstratified, or mixed, and it is to be regretted that analysis was not undertaken of those torcs from the nested/layered hoards of G, H and, in particular, L. Although surface alloy composition data, in artefacts with various surface treatments, are not wholly indicative of what lies beneath, they do provide a general idea of whether an artefact is rich in one metal or another, and this in turn can help with the understanding of manufacturing technologies. That such analysis has not been carried out, when the technology is readily available at the British Museum to do so, is a great regret.

…and finally.

A reference to casting, first used in an earlier paper by the British Museum Science team (Meeks et al 2014, 151), is curious. In the 2014 paper, this single reference is used in support of the casting method for torus torcs:

and in the current Snettisham volumes the Meeks et al 2001 reference again occurs (p. 459) as an explanation for casting, this time in support of a method for preparing the moulds ready for the addition of the molten gold alloy, but again, as the single reference for an entire torc casting process:

However, both this reference and the Tulp et al 2001 reference included in the current work (p. 459) involve the same piece of experimental archaeology, carried out in an attempt to replicate the solid, bronze, single piece, casting of a Merovingian die from Tjitsma. I will be completely honest here in saying that, had I published this as a supporting reference for the production of a hollow, thin-walled, cast torus torc, I would have been hauled over the coals during peer review…

Summary

To sum up. although there is much to celebrate in the publication of The Snettisham Hoards and the volumes contain evidenced and valuable work, when it comes to the sections on torc manufacture and technology there is much that has been omitted or glossed over. As the largest collection of torcs ever found in Europe, the Snettisham torcs deserve to be accurately recorded and interpreted and, unfortunately in these volumes that has not happened.

As has been shown, collaboration with experienced gold/metalsmiths is an absolute necessity for accurately interpreting manufacturing technology. That this has not happened in this case means an opportunity has been wasted and that is to be regretted.

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to various members of the torc collective and other craftspeople who offered their thoughts: Giovanna Fregni, Hamish Bowie, George Easton, Bob Davies, David Loepp, Patrick Conlin, Graham Taylor and all those who contributed to Damn Clever Metal Bashers. Skilled craftspeople are often ignored by academia when their insights should be front and centre of any work which aims to understand the craft of the past.

In thinking about and writing this article, I really missed the input of Ford Hallam: I hope you can see this Ford, wherever you are.

References

Clarke, R.R. 1951. A Celtic torc terminal from North Creake, Norfolk. Archaeological Journal 106, 59–61

Hunter, F. 2018. The Blair Drummond (UK) hoard: Regional styles and international connections in the later Iron Age. In Schwab, R; Milcent, P-Y; Armbruster, B & Pernicka, E (eds), Early Iron Age Gold in Celtic Europe: Science, technology and Archaeometry. Proceedings of the International Congress held in Toulouse, France, 11-14 March 2015, 431-440. Rahden: Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH

Machling, T. 2022. Pattern and purpose: a new story about the creation of the Snettisham Great torc. https://bigbookoftorcs.com/2022/05/29/pattern-and-purpose-a-new-story-about-the-creation-of-the-snettisham-great-torc/ DOI 10.5281/zenodo.10511411

Machling, T. 2024. The Staffordshire Torc Odyssey: 14 Needwood Forest up close. https://bigbookoftorcs.com/2024/09/04/the-staffordshire-torc-odyssey-14-needwood-forest-up-close/

Machling, T. & Williamson, R. 2016. ‘The Netherurd torc terminal – insights into torc technology’. PAST: The Newsletter of the Prehistoric Society 84 (Autumn 2016), 3–5.

Machling, T. & Williamson, R. 2018. ”Up Close and Personal’: The later Iron Age Torcs from Newark, Nottinghamshire and Netherurd, Peeblesshire’. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 84, 387–403.

Machling T & Williamson R. 2019. ‘”Damn clever metal bashers”’: The thoughts and insights of 21st century goldsmiths, silversmiths and jewellers regarding Iron Age gold torus torcs’ in C. Gosden, H. Chittock, C. Nimura & P. Hommel (eds), Art in the Eurasian Iron Age: Context, connections, and scale. (Oxford).

Machling, T. & Williamson, R. 2020a. ‘Investigating the manufacturing technology of later Iron Age torus torcs’. Historical Metallurgy. 52, 2 (for 2018), 83-95.

Machling, T. & Williamson, R. 2020b. A rediscovered Iron Age torus torc terminal fragment from ‘Near Stowmarket’, Suffolk. https://bigbookoftorcs.com/2020/02/02/near-stowmarket-torc/ DOI 10.5281/zenodo.10511422

Machling, T. & Williamson, R. 2021. Rings of truth: New insights into torc technology. British Archaeology. September/October 2021, 42-47.

Machling, T. & Williamson, R. 2023a. Beyond Snettisham: a reassessment of gold alloy torcs from Iron Age Britain and Ireland. https://bigbookoftorcs.com/2023/06/23/beyond-snettisham-a-reassessment-of-gold-alloy-torcs-from-iron-age-britain-and-ireland/ DOI 10.5281/zenodo.10629085

Machling, T & Williamson, R. 2023b. The sheet torus torcs from Britain: an update. https://bigbookoftorcs.com/2023/12/28/the-sheet-torus-torcs-from-britain-an-update/ DOI 10.5281/zenodo.10511424

Machling, T., Williamson, R. & Fregni, G. 2023c. ‘All the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order’: The riddle of the ‘Pulborough Area’ torc from Sussex. https://bigbookoftorcs.com/2023/10/19/all-the-right-notes-but-not-necessarily-in-the-right-order-the-riddle-of-the-pulborough-area-torc-from-sussex/ DOI 10.5281/zenodo.10511405

Machling, T; Williamson, R. & Hallam F. 2019. ‘Going round in circles: the relief decoration of Iron Age gold torcs’. PAST: The Newsletter of the Prehistoric Society 93 (Autumn 2019), 3–5.

Meeks, N. Tulp, C. Söderberg, A. 2001. Precision lost wax casting. Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop. Experimental and Educational aspects on Bronze Metallurgy, Wilhelminaoord 18 – 22 October 1999. in Tulp, C. Meeks, N. Paardekooper, R. (eds). Vereniging voor Archeologische Experimenten en Educatie. Leiden.

Meeks, N., Mongiatti, A. & Joy, J. 2014. Precious metal torcs from the Iron Age Snettisham treasure: Metallurgy and analysis. In E. Pernicka & R. Schwab (eds), Under the Volcano: Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Metallurgy of the European Iron Age (SMEIA), 135–56. Rahden: Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH

Tulp, C & Meeks, N. 2000. The Tjitsma (Wijnaldum) die: a 7th century tool for making a cross-hatched pattern on gold foil, or a master template? Historical Metallurgy. 34, 1 (for 2000), 13-24.

Tulp, C. Meeks, N. Paardekooper, R. (eds). 2001. Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop. Experimental and Educational aspects on Bronze Metallurgy, Wilhelminaoord 18 – 22 October 1999. Vereniging voor Archeologische Experimenten en Educatie. Leiden.

7 Replies to “The Snettisham torcs and the British Museum”