By Tess Machling

[A download/print PDF version can be found at the end of the paper]

Featured image: Gallo-Roman Museum, Tongeren

As any of you who follow me on social media will know, over the years I have become increasingly concerned about who owns, or who believes they own, our heritage (and by ‘our’ I mean every single one of us across the world) and those who attempt to limit the way we can share heritage information.

From access to information through to the ability to be able to disseminate research, for me the obvious concern regards artefacts. In my case, it’s torcs but really it could be anything. This problem encompasses research, publication – and now potentially artefact replication – and to say that the developing situation is concerning would be a huge understatement.

These issues most obviously affect ‘prestige’ items and it is no coincidence that the items most commonly affected are those most folks would think of, and which are even legally defined, as ‘treasure’: gold, silver and all things bling! Gold and silver artefacts, or anything rare and/or attractive, demand high prices in the retail market and are coveted by ‘owners’ and collectors and lauded in the public sphere.

The knock on of this monetary acquisitiveness is a broad, nationwide, interest which is often limited only to ‘treasure’. Although often excused by those involved as their being only interested ‘in history’, a quick scan through the detecting groups across social media will quickly bring forth numerous examples of finders being ‘robbed’ or ‘conned’ out of what they deem they are due for the finding of such artefacts. This ‘Gollum Effect’ is rampant, often even affecting museums, where monetary worth and rarity lead to control over the right to reproduce imagery of these artefacts.

Background

Following a recent boom in the hobby of metal detecting, there are an increasing number of finds being uncovered by detectorists who may – or may not – be reporting their finds (see HERE for my previous paper on this issue). Many detectorists – but not all – are now claiming ownership, and ever higher payments for their finds. In legal terms, this payment is known as a ‘reward’ (although I really think we need to get away from this terminology as it masks what the real, transactional, situation is).

Finds Liaison Officers in the Portable Antiquities Scheme are underpaid and overworked as the system becomes overwhelmed by the, literally, millions of finds that are now being uncovered. As the archaeology world debates whether we should actually be excavating *anything* else until the massive backlog of archaeologically derived data can be adequately preserved, the rest of the world keeps digging…

Often such items are described by finders as having been ‘saved’ or as ‘mine’. Each important (read: ‘monetarily valuable’) find is widely broadcasted, egged on by a media looking for the ‘personal’ story in any discovery, in a way which is very much defined by the finder. Such media coverage often does not mention the archaeological background or relevance, legal requirements or the Portable Antiquities Scheme. As such, the status of that artefact as being a product of our islands’ shared heritage, and the wider picture of out-of-control artefact discovery, is often reduced or negated. The find is all.

Recently we are also seeing similar issues occurring in archaeologically excavated material where title of ownership has not been transferred to a museum (or similar) prior to excavation and where, as such, finds are being effectively dug up for private ownership. Finds are also being discovered on digs by organizations with little archaeological supervision, training, or understanding of the wider archaeological discourse regarding archive deposition, information dissemination and media handling.

Further recent developments, although not yet embedded, include attempts to control access to artefact information to those who would like to reproduce or replicate some of these finds, and in one case, the removal of a replica for sale from an online selling site.

Most worryingly, as an assumption of personal ownership becomes the norm, possessive wording used in association with these finds can further exacerbate claims to heritage by those, e.g. white nationalists, who aim to pervert our history for their own unpleasant purposes.

Although recent modifications to the 1996 Treasure Act allow for the possibility of the state acquiring any metal/in-part metal items if they can be shown to provide ‘an exceptional insight into an aspect of national or regional history, archaeology or culture’ in reality, where museums are hugely underfunded and are facing multiple claims on their funds from an ever increasing number of artefacts, many archaeologically important finds, even gold and silver ‘treasures’, cannot be acquired and are being lost to private ownership and/or export from these islands. In addition, this modification to the law only became enacted in 2023, with any non-precious metal finds made before this date not coming under the new rules. Many have been sold on or lost from public view.

Once privately acquired anything can happen to these items: even if lovingly cared for by their current ‘owners’, archaeologists know that archives and finds can quickly become skip-fill upon the death of an individual. In the worst case, artefacts can be melted down or resold, with each resale removing the artefact ever further from knowledge of its location. There is nothing legal to stop any of this once an artefact has been declaimed and, as such, we – all of us – have no absolute rights to access what should be in the public domain.

Image rights

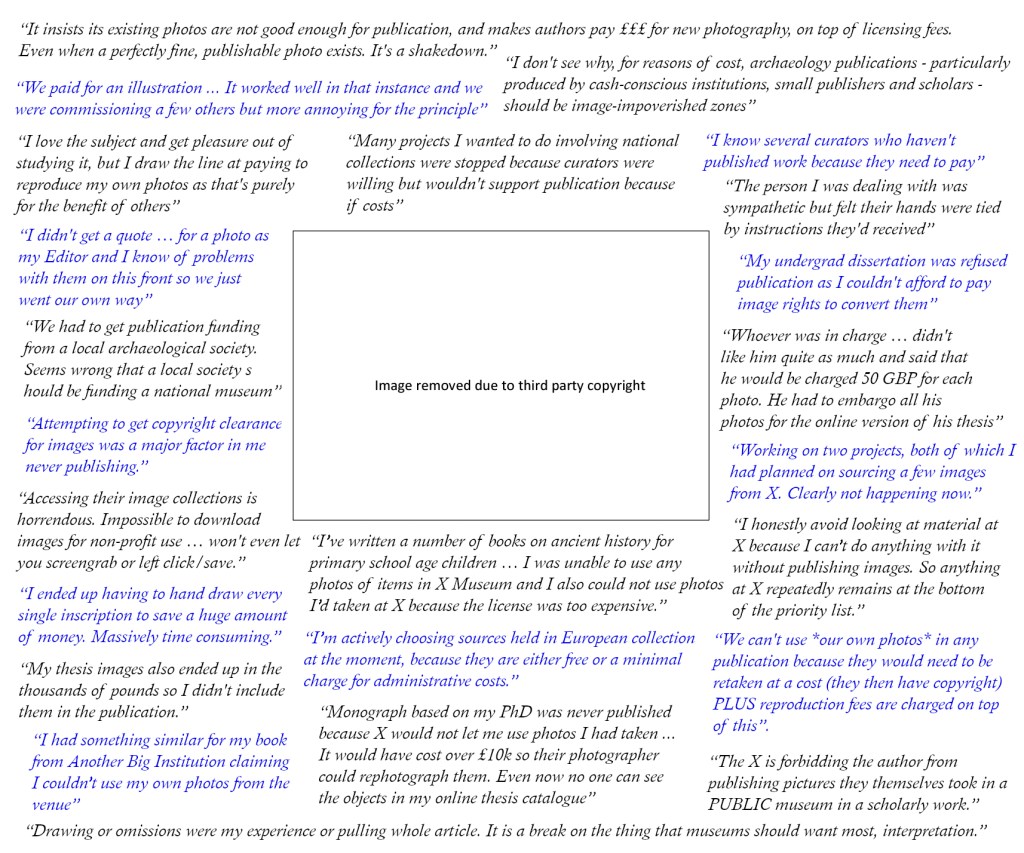

In addition to the above, historically or recently acquired treasure finds in museums are sometimes subject to access control: often research cannot be published as researchers are forced to sign forms that restrict their use of photographs in published research, even if that research is published in open access, not-for-profit, media. Below is a graphic I created from canvassing the experiences of many archaeologists. It is a tough read.

In addition to these problems, pay-walled research often denies access to papers to anyone beyond academic institutions: if you cannot afford to pay, you cannot learn or carry out in-depth research. Those often without access includes those in the replication/craft world, many of whom exist beyond the world of academia.

Replication

As part of my research, I have worked with, or know, a number of replica makers, craftspeople, goldsmiths, silversmiths, jewellers, etc. All have many years of experience, training and knowledge and none are well paid: they eke out a precarious living doing what they love.

Yes, if you look at, say, a replica Iron Age sword costing £8000 or a replica prehistoric pottery urn which retails at £360, that looks like a lot of money, but once you break down the costs into research time, materials and labour you will often find that these folks are barely earning minimum wage, and can go for extended periods where they have no work, often taking on secondary jobs, to pay their way. My family were all goldsmiths in a continuous line back to the 1700s and my great-grandfather even helped set the diamonds in the British crown jewels, but they were never paid much for their work. The same goes for present day goldsmiths, not one of whom I’ve ever met has got rich from their craft.

Increasingly 3D printing is overtaking replication, but a 3D print cannot tell you how something was made, or how it really feels in the hand: it is a pale representation of the real thing. In short, we need to be supporting our craftspeople, not limiting the possibilities for them in helping us to understand the objects of the past, and making a living along the way.

Torcs

I have always passionately believed that everyone should have access to archaeological information and this was largely behind my decision to create The Big Book of Torcs. This is also why I have a wide social media presence, and try to disseminate my research via a broad range of media types, from blog posts, magazine articles and podcasts, through to peer reviewed academic papers and books.

I earn nothing from my research, and any monies I do earn from lecturing and teaching about torcs are ploughed back into research costs like travel and publication. I do not earn a lot from my job as an administrator and researcher, and so I am certainly not in a position of particular privilege as regards this research. Like detectorists or community archaeologists, it is my hobby. But I am lucky, in that I was educated in the time before university loans, and I have good contacts in the archaeological world from having worked in the sector, in one way or another, for the last forty years.

Throughout the course of my torc research I have come across many finds in private ownership and have spent a lot of time – with varying success – trying to locate these items and then to negotiate access, or publishing rights. Without either access, or good publicly available metrical data on a torc, put simply, I cannot carry out my research. Currently I am awaiting access permission to one artefact that I have been wanting to see for over three years. The research into that artefact – and those related to it that I have seen already – will be on hold until this can be negotiated. In other cases, that access has not been possible and the research has not been carried out.

As mentioned previously, this isn’t just about privately held finds: this issue affects some, though certainly not all, museums too. It is a constant, and time consuming, battle and is certainly not similar to the situation I experienced as a pottery researcher, where most material was generally accessible.

Summary

I hope this goes a little way to explaining my vocal responses over the years and will help others to understand why public ownership, and an urgent national investment – both psychological and monetary – in this endeavour, is critically needed.

We as individuals or groups do not ‘own’ these artefacts: we, as a nation, hold them in trust for anyone who might be interested in them in the future.

2 Replies to “‘My precious!’ Some thoughts on access and ownership of artefacts.”