by Tess Machling

[A download/print PDF version can be found at the end of the paper]

This paper can be cited as: DOI 10.5281/zenodo.15264348

Following on from my earlier blogs on detecting and torcs and access and ownership of finds, I wanted to look in greater detail at these topics and discuss the impact that privately-owned torcs and image rights restrictions have had on my research and my ability to carry it out. I hope that by looking at the recent furore surrounding access to another archaeological artefact – the Norton Disney dodecahedron – and relating it to my own experiences, it will become clear that the holding of finds in private hands, and restricting access/rights to finds/images, has a direct – and negative – impact on research.

Unfortunately, all too often the finds which researchers have trouble accessing or reporting on are those that most people think of as ‘important’ or valuable – whether precious metal or not – and those objects, of any type, now in private ownership. As discussed in a previous blog, access to finds often, ultimately, depends on monetary worth. This is what I call The Gollum Effect: a situation where rare/monetarily valuable/covetable finds are acquisitively kept in private ownership and effectively out of reach of the public gaze. Mostly they are antiquarian or detected finds, but recently a find from an organised archaeological excavation, the Norton Disney dodecahedron, potentially sets a worrying precedent for future artefact research.

The Norton Disney dodecahedron.

Found on a community archaeology excavation (apparently supervised by a commercial archaeological company, Allen Archaeology) in June 2023, the Norton Disney dodecahedron soon became an internationally renowned artefact with wide news coverage and a 2024 feature on the hugely popular Digging For Britain BBC television programme. Although the dodecahedron has been loaned to various museums in the north of England during 2024, the object remains in the private ownership of the landowner.

A justifiable request?

In April 2025, the Norton Disney History & Archaeology Group requested that eBay remove a replica of the Norton Disney dodecahedron from sale. Initially, the request appeared perfectly reasonable and seemed to have been driven by the use of several uncredited NDHAG photos in the eBay sale listing. However, subsequent Twitter and Bluesky posts (now deleted) and a BBC article and interview suggested that the group had actually requested that the make be removed because it was ‘an unauthorised copy’ and that ‘the seller does not have permission to make copies or sell them’ (NDHAG, Twitter post, 26th March 2025).

A thread on Bluesky (now partially deleted) by ‘Dodecehedra Girl’, a PhD student studying these objects, also confirmed the same. Furthermore, the Portable Antiquities Scheme entry (under LIN-BC9890) at this time also claimed that ‘a license from the private owner of that object is required before creating and distributing a 3D model of the dodecahedron’.

Clearly, the licensed permission for replication requested by NDHAG and the landowner is not legally enforceable as any artefact is the copyright of the maker (a two thousand year old one, in this case!!) and, unless it could be proved that a modern maker had created the replica directly from the group’s images (for example, via a 3D photogrammetry model), there would be no case to answer. Even consulting the group’s photos as source material for a replica – in any media – would not be legally, or even ethically, wrong. Nonetheless, eBay removed the listing and the NDHAG publicly celebrated their victory.

It should be noted here that museum replica makers mostly do not create 3D prints, they use their skill and experience to recreate a copy of an artefact, in the original materials. In the case of the Norton Disney dodecahedron, a replica maker would first make their own full-size casting model, created in a medium like wax or epoxy, using measurements and photos of the original artefact, but very much their own work. This model would then be used to create a mould into which molten bronze would be poured. The modern investment casting method above would be very similar to the lost-wax method used in antiquity – where wax would have been used to create the casting model, before the wax was covered in clay, the wax burnt out and the previously wax-filled void filled with molten bronze and then the clay cracked off.

The photos, illustrations and measurements a replica maker would use can be gleaned from a number of sources: from publications, images shared widely across the internet, from museum catalogues, or even – possible in the case of this artefact – their own photos taken in one of the museums where the dodecahedron has been on display. Obviously, access to the object itself and the ability to measure and photograph the elements most relevant to the make would be the preferred solution, but many museum quality replicas are made without seeing an object in the flesh. However, with the dodecahedron in private ownership, and the images restricted, such a make would currently be very difficult.

The Portable Antiquities Scheme entry.

In addition to the above, and unlike standard PAS entries, the photos used in the April 2025 LIN-BC9890 Norton Disney dodecahedron entry did not include measurement scales, and were non-PAS copyrighted. The PAS normally offers its images under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 deed attribution, which allows any sharing of images. This was not the case for this find.

The following was also included in the PAS entry: ‘However, the owner is choosing to remain anonymous. There will be a published report that will be submitted to the Lincolnshire Historic Environment Record (HER) although again the report will still be copyrighted by its author(s), so again, permission is required to use that data for any models’. As such, the rights to the find and its metrics appear to be restricted without permission of the dodecahedron’s private owner.

It should be noted that the dodecahedron was not a detected find, nor was it classed as ‘treasure’ under the terms of the 1996 Treasure Act (but more on that later) and so it is uncertain how the artefact came to be listed on PAS, or why the unusual clause had been added to the listing.

However, as has been pointed out by Andy Mabbett, a search of the Wayback Machine for earlier versions of the PAS entry shows a number of alterations since the listing was first made in January 2024, with the original entry showing scaled photos and none of the later reproduction caveats. As of today, 22nd April 2025, the PAS entry for LIN-BC9890 has been deleted. As such, most public information regarding the Norton Disney dodecahedron has vanished. So what is going on and why is it a worry?

Private ownership

Private ownership of finds goes against everything I, as an archaeologist, believe in. When I was working as a field archaeologist I found a number of important finds – the most spectacular of which was a number of 17th century cannon! As a torc researcher, I also regularly get to ‘play’ with some of the most rare, expensive and blingy artefacts that have ever been found in these islands. Not once, in my entire forty years in archaeology, have I felt ownership for any of these artefacts.

For me – and part of the reason why I created The Big Book of Torcs – the fun is in the sharing of information, in taking people with me on my research journey. Many times other specialists or interested parties have asked for images and/or measurements and I have obliged, and most data I have is published, free, on the Big Book of Torcs so that it is accessible to all. I have had the very great privilege to see and study these items, so why not share what I have seen and found out? I see a torc and you all get to see it too. I’ve also shared my research and images with the organisations I have worked with: often museums don’t have images of their own or have incomplete data regarding their artefacts, and I can help provide them with photos and further information.

Private torcs.

Over the course of my ten years researching torcs, I have often come across torcs which are in private ownership. Some, like the Near Stowmarket torc piece, which was found in 1996, just prior to the 1996 Treasure Act, were retained by the finder and – once they were tracked down – could be studied. However, even in the Near Stowmarket case, starting from nothing more than a brief British Museum record of the find from when it was reported nearly thirty years ago, made tracking down this torc piece difficult and took almost thirty emails to colleagues and others across East Anglia and the Iron Age research world to locate.

In this case I was lucky in that 1) the finder was still alive and was 2) in the area; 3) they were still reporting their finds and as such 4) were known to the local PAS team and finally that 5) they had retained the torc piece rather than having sold it or had it melted down. In addition, the finder retained good records regarding the location of the findspot, etc. This really was the perfect private owner!

However, the Knaresborough ring, another pre-1996 Treasure Act find was less of a success. Put up for auction in 2022 – and I only became aware of this thanks to a lucky spot of a newspaper article – the circumstances and precise findspot of this important Viking adapted torc piece is unknown. Because the seller – and buyer – refused to allow me access to study this torc piece, it remains examined from only a handful of auction house photographs. There is so much more I could say about this important find, had I only seen it in the flesh. Also, had Yorkshire Museum been successful in buying it (unfortunately the final auction price was more than they could afford), it would still be in public hands allowing myself – and future researchers and museum visitors – the chance to see, study and enjoy this important artefact.

After its auction sale in 2022, despite the new owner promising to lend it to a museum, the ring has not been seen since and its current location is unknown: it is now lost from public view.

In addition to pre-1996 Treasure Act finds like the above, there are any number of torc pieces or torcs which, although reported to PAS after 1996, were returned to the finder either because they did not comply with the 1996 Treasure Act criteria, or if they did, were declaimed by museums who often could not afford to buy them. This includes the Shenstone torc and any number of torc pieces which can be found in the PAS database. The whereabouts of these torcs largely remains unknown and finders who have had these finds returned to them have no obligation to conserve, keep, not melt down, or sell, any of these finds. Put bluntly, if they are not in a museum they are not safe.

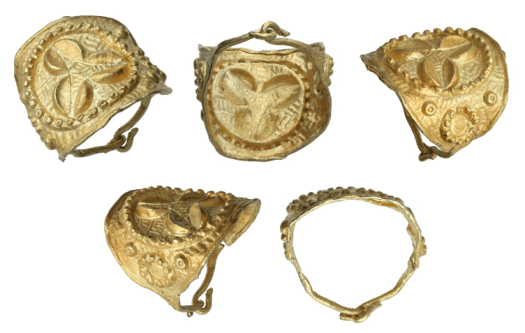

In addition to the above, there are a number of torcs that have appeared at auction houses over the years: the most spectacular and probably of greatest research interest to me is this gold, cage terminal, torc of unknown origin which was sold at Christie’s New York auction house in 2013.

This type of cage terminal torc is exceedingly rare, with only five examples previously known. All of these examples are broken and partial, and all five come from the site of Snettisham in East Anglia. The Christie’s torc would have been an important one to study, but its sale into private ownership, and location in the United States, makes this impossible.

As I was writing this blog, I also became aware of another gold torc from an unknown location, that had also been sold at Christie’s. It had first been auctioned in December 1994, and then reauctioned in July 2023. By late 2024, it was subject to a temporary export bar, with a price of £45,000 being settled to secure it for the nation. This torc, of a simple ring terminal twisted wire design, is interesting due to its reported gold alloy composition: at 97% gold this is high for a gold torc and would be of significant interest. I don’t know if it was saved, but I’ll be trying to find out. But once again, even were it rescued, the £45,000 price tag for what should belong to all of us, leaves a bitter taste. If it hasn’t been ‘saved’ it will have gone the way of the Knaresborough ring: except in this case it will have been taken to another country.

This is why the private ownership of the Norton Disney dodecahedron is such a concern: reproduction rights aside, that the dodecahedron has not been titled to a museum means that, even if the current owners look after the artefact, there are a number of events in the future that could put it at risk: What conservation/preservation procedures are in place to ensure the continuing stability of the artefact (bronze disease can literally turn an artefact to dust)? What plans are in place should the owner become unable/not wish to look after the artefact anymore? What happens if they fall on hard times, get burgled… die? In private ownership there is no obligation to make any preparation for these eventualities and one of any of the above can at best remove access to an artefact or, at worst, result in its destruction.

These are all really uncomfortable questions, but all too often archaeologists are called in to deal with private archives/unpublished sites/finds collections etc that have turned up in auctions/skips/house clearances or as the unwanted belongings of deceased individuals or those whose circumstances have dramatically changed. Trying to work out what came from where and when is no easy task when you no longer have the person around to ask about their often, esoteric, curation practices. And, yes, this is a fault that archaeologists and museums can also be guilty of, but in almost all cases museums – with their organised cataloguing/documentation, access rights, conservation-friendly storage/display environments, legacy procedures, statutory rules, etc – are the safest place for any archaeological find. This ensures that artefacts, even if not on display, are there, in the public domain, in perpetuity.

A further issue is access: even if the whereabouts of a find in a private collection is known, as I experienced with the Knaresborough ring, there is no obligation for an owner to grant research access to an artefact and, for owners, a steady stream of academics can be an unwanted life interruption, which many are not prepared to put up with. The system in a museum means that finds visits are booked in and, from my experience, the complementary insights of researchers and on-site curators also makes for better research outputs .

That the dodecahedron came from an archaeological dig, where museum title to finds should be secured in advance but was not, although not uncommon, is of great concern. Although the 2023 changes to the 1996 Treasure Act, should now allow for the state acquisition of any metal/in-part metal items if they can be shown to provide ‘an exceptional insight into an aspect of national or regional history, archaeology or culture’, I fear that – with museums having so little money to spare – this will not be the last archaeologically important artefact that has gone into private hands that we will hear of. Ironically, had the Norton Disney dodecahedron been found only four weeks later than it was it would certainly have qualified under the ‘significance’ criteria of the newly modified 1996 Treasure Act. We can only hope that further important artefacts from sites like this will too.

Image wrongs.

Even where a museum title has been settled with archaeologically recovered artefacts, a further barrier I often face is that of image rights: any publication – even in a non-profit journal, where the author receives no payment for their research – often results in museum charges to the researcher for the reproduction of artefact images. In my experience, the majority of local and regional museums do not insist on such charges, and instead appreciate the researching of their artefacts, whilst also recognising the PR potential of the dissemination of research based on their collections. Several of the National Museums, the National Museums Scotland most notably, only ask for a nominal fee per publication and have in some cases granted me usage in perpetuity.

Others, most notably the British Museum, make image usage almost impossible: to gain off-display research access to torcs at this museum, I am – on each occasion – asked to sign a form which states ‘I have read the Study Room regulations, and undertake to observe them. Where photography is permitted, any photographs taken will be for personal study only’: if I don’t sign, I don’t get access to artefacts.

In addition, even the terms of the British Museum Visitor Regulations, which cover photography in the galleries, state that, ‘You may use your photographs, scanned data, film and audio recordings only for your own private and non-commercial purposes.’ Sadly ‘commercial use’ is defined to include ‘Anything that is in itself charged for, including textbooks and academic books or journals’. There is no exception for non-profit journals, articles by unfunded independent scholars or publications where authors do not receive a payment. There are a few images in the Museum’s image library which are available under ‘CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 International’ deed. However, this does not apply to most torc images contained in the British Museum catalogue or to any photos I have taken, which are usually close-up technical shots of details, etc.

In the case of my own photos, an extra level of – what can honestly be called – crazy bureaucracy, occurs where the museum will insist on retaking my photos if I wish to publish them. These photos will be taken, by their photographers, in their own studio and I will then be charged for this service – with an additional standard image rights fee added to this cost! For one paper I wrote, I worked out that the image rights alone would have cost upwards of £5000 had I attempted to publish all forty-one images and so we got the paper independently peer-reviewed and published it on the Big Book of Torcs! [As a further issue, many journals and books will only allow a very small number of images in any publication… another reason why The Big Book of Torcs works better!].

For another publication, I was forced to apply to a local archaeological society to obtain a grant for the £186 necessary for me to be able to publish two stock photographs from the British Museum collections (I had given up on the few hundred pounds on top of this charge that using my own, re-photographed, images would have cost). Luckily, in the end, these photographs were not used and so there was no charge to the local society, but we really should not be in the position where a local archaeological society is funding the image rights costs of a national museum!

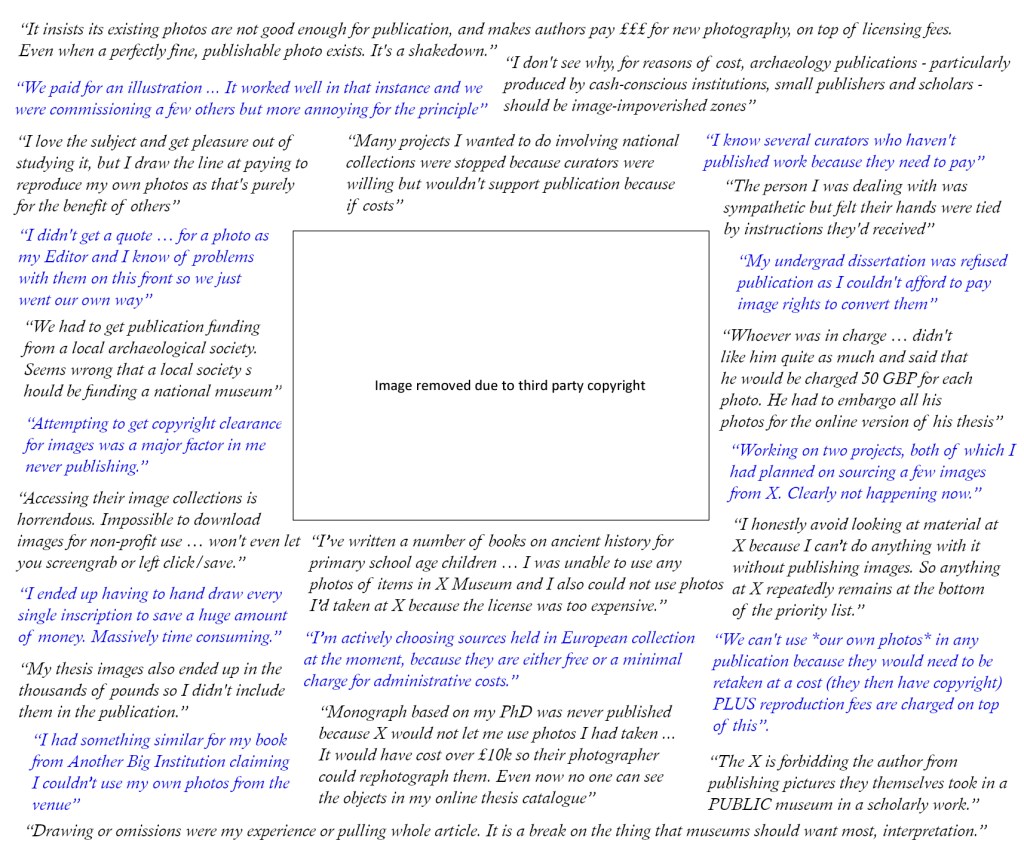

To try and find out how prevalent this situation was, I put out a call on social media for archaeologists’ experiences of image rights issues and the results were used to create the image below:

A huge number of people responded and, although I didn’t go into detail at the time, the majority were issues with the British Museum, who it turns out even charge their own curators to publish images!

There were also several examples of PhD students who had never published their doctoral theses because they could not afford the image rights costs that publication would involve. To me, the most stark of these cases was that of Dr Ian Marshman, whose 496 page, highly illustrated, thesis ‘Making Your Mark in Britannia: An investigation into the use of signet rings and intaglios in Roman Britain’, has been uploaded to the University of Leicester repository, but contains almost no images, just blank boxes where photos of British Museum artefacts should be.

[The irony of this being a thesis on intaglios, artefacts which were stolen in their hundreds from the British Museum and which went unnoticed – thanks to no public photographs being available – is not lost on me…]

Image rights are not just an issue for archaeology: any researcher using museums/collections is often affected. Within the wider world, art historian Dr Bendor Grosvenor, has written extensively on this topic, as has open access and cultural heritage specialist Dr Doug McCarthy, both of whom have been gracious enough to include the archaeological experience in their work.

Although the law has recently changed for 2D works, where reproduction is now possible, for 3D artefacts the often restrictive image rights policies of organisations such as the British Museum, still stand. However, Freedom of Information requests have shown many museums actually make an overall financial loss in their image rights ventures (…and that’s without the knock on monetary impact of the loss of goodwill and the lost PR opportunities of easily disseminated research). However, with the recent changes to 2D rights I hope that continued pressure will mean that artefacts are soon included in the free usage laws: this cannot come too soon.

Some good news.

However, as I mentioned previously, with many museums there is reason to celebrate: although I am sure there are many more that can be added to this list, from my own personal experience, staff at the National Civil War Centre Newark, Yorkshire museum, Potteries museum, Weston museum , Brighton museum, Worthing museum, Barbican House museum, Leicester museums, Norwich Castle museum, Colchester Museum, Tamworth Castle museum, National Museums Scotland and the Royal Collection Trust have never been anything other than helpful and have often waived all image rights fees, seeing the work of researchers as a chance to promote the objects in their collections. Yorkshire museum even went so far as to take photographs for me, not charging a fee for this service and allowing their images to be used in perpetuity under a CC BY-SA 4.0 deed. Museums such as these are to be hugely commended for their attitudes towards scholarship, especially in such straightened times.

To be honest, such positive and welcoming attitudes, even if looked at only from a commercial perspective, are a no-brainer: researchers will spread the word of how lovely these museums are, their museums get higher coverage in print and online, and they get to share their artefacts with the world, for no cost.

British Museum, take note.

Paywalls

A further hurdle to public access is paywalled academic publications. Unless you have library access through your university, organisation or workplace, individual papers can cost upwards of £20 each to read. For those without access, often independent scholars, this makes study and research very difficult. Although Open Access publishing is becoming more common (albeit often funded by the authors/their projects paying a fee for this option), there are still a number of papers which don’t fall under this category.

As I know only too well – having worked for the Prehistoric Society for thirty years – most societies are run entirely by volunteers, with only a few organisations having paid editorships (and in most cases even these are token honorarium, rather than wages). As such, for smaller publishers and local – and even national – societies, it is understandable that these income streams are necessary for the organisations to be able to operate. In most cases – beyond the large publishing houses – it is difficult to see how fully free access will be possible.

However, that is not to say that we shouldn’t try to find alternative sources of funding (for example by offering free online copy funded by commercial book sales), or that the bigger publishing houses shouldn’t offer more free outputs. We need to be moving away from paywalled research.

Public rights

As has been shown above, there are many limitations to the work of an artefact researcher: be it privately owned finds, paywalled research or exorbitant image rights costs, there is much that means research is often difficult to achieve and/or publish.

Although many may not understand the widespread concern in the archaeological world regarding the private ownership of, and restricted access to, the Norton Disney dodecahedron, I hope that by sharing my experiences as an artefact researcher, I might have gone some way to explain that concern. I really hope the dodecahedron finds its way, freely, into a public museum collection very soon.

But I’d like to finish on a positive note, with a huge thank you from this researcher to all those who donate their finds to museums for free, and to those museums who are only too glad to welcome researchers in and to help them publish their work. I can also guarantee that the Big Book of Torcs will always be free to access. Afterall, it’s good to torc (freely!)

4 Replies to “Private finds and image rights… and wrongs.”