(‘Iron Age Dialogues’ conference, Cardiff, 30th April to 2nd May 2025.)

by Tess Machling

[A download/print PDF version can be found at the end of the paper]

This paper can be cited as: DOI 10.5281/zenodo.15389794

Introduction

Although there is an intention to publish the proceedings of the Cardiff conference, for me, publication in print will once again mean I will be facing significant image rights costs, which will not allow for the full publication of everything I said in my talk: I will need to adapt what I want to say to fit the needs of a supposedly ‘commercial’, printed volume (for more about the problems of how ‘commercial’ publication is defined, see here).

With this in mind, I thought I would share the slides and commentary of my talk here. If you are a regular visitor to The Big Book of Torcs, you will be aware that I work with a team of goldsmiths, silversmiths and jewellers, and that my work comes from a craft perspective on gold: how torcs were made and what that can tell us. This talk was very much a result of this work, and argues that to ignore the craft perspective, as sadly so often happens, can cause all manner of problems with interpretation. In short, we cannot tell much about widely what an artefact means, unless we know how it was made.

So in this spirit, this is my talk: I do hope you enjoy it.

Iron Age gold: Time for a shake-up?

Gold in Iron Age Britain consists of a small suite of artefact types: thousands of coins, a few ‘v’-shaped finger rings, a couple of bracelets and, apart from that, the bulk are torcs, likely made both for the arm and the neck.

There is also a hiatus in gold work from the later Bronze Age to the middle Iron Age. However, almost each time a new torc/torc assemblage is found, the pattern changes: for example, the finding of the Leekfrith hoard, in 2016, put the dating of British-found gold torcs earlier by a couple of hundred years.

The majority of torcs that have been found have no context and were not excavated archaeologically. Even with the excavated torcs, several have only had the findspots excavated, after the torc/s have been removed. For more about this, see here. As such, we have very little contextual information for torcs, which makes interpretation, dating, etc difficult.

We also have this huge site at Snettisham, with fourteen hoards, and hundreds of torcs which tends to dominate the narrative of Iron Age torcs. However, the normal pattern of deposition is of 3-4 torcs in a single deposit. As such, we need to bear in mind that Snettisham would seem to be an anomaly.

A craft perspective.

I look at gold from a craft perspective and the slide below summarizes some of the problems I’ve encountered in gold studies, and a few suggestions of how things could be improved. If you want to delve into more detail, my issues with the recent Snettisham publication have been raised here.

We need to find a better way…

The origins of gold.

In this next section, I want to look at Iron Age gold from a craft perspective and, via a few examples, show how current theories may not be offering accurate insights into Iron Age gold and gold-working.

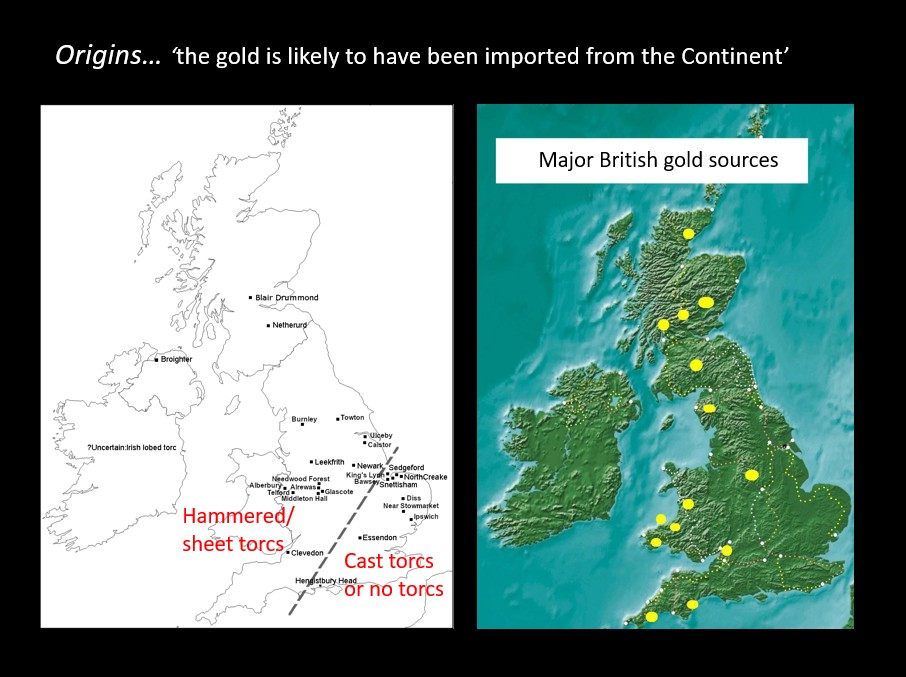

The idea that Iron Age British gold is imported and recycled is long standing. For a discussion of this, please see here. However, if we look at gold sources, this is not necessarily the case. There is a rough line running from about Weymouth to the Wash, on one side of which are found predominantly sheet work/hammered torcs and the other, predominantly cast torcs.

Could this relate to ancestral working traditions in areas where gold is found, in the north and west, and which is not seen in the south and east, which have an absence of gold sources, and where a casting technology (probably in bronze) is more traditional?

If we look at where gold is uncovered today, there is an abundance of material being found, although this material is largely unknown in the archaeological world. The examples below have been found in Scotland over only a few years, within a local area: I can’t say more than that, but it is enough to say that it is a lot of gold from a very small area!

But what this shows is that gold is still abundant if you know where to look, and imagine how much more there was thousands of years ago, before the alluvial sources had been stripped out.

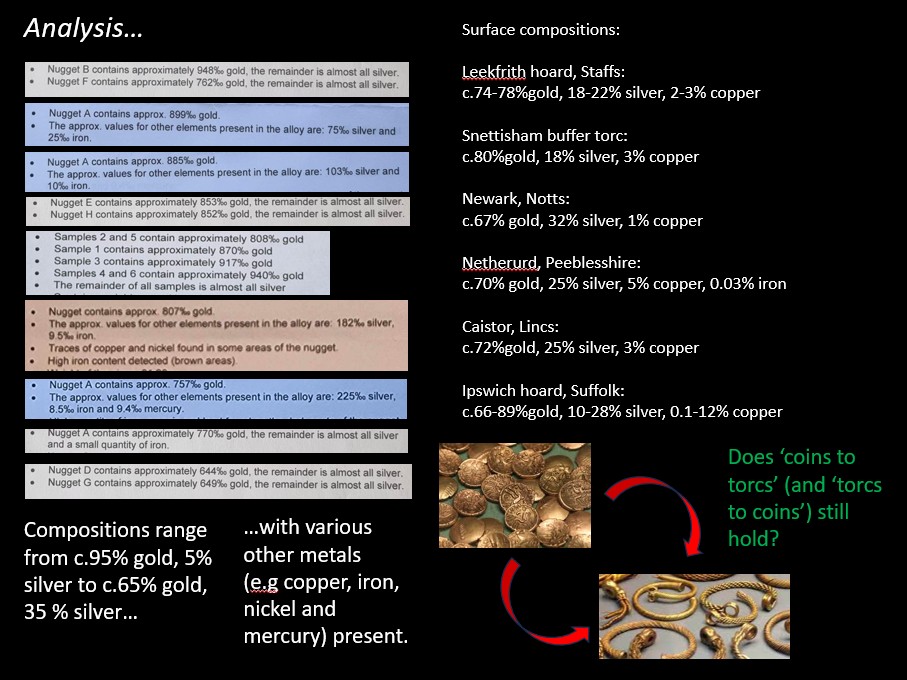

The finder of the gold nuggets kindly had them assayed (composition tested) for me, and the results can be seen below: not hugely different to the percentages found in several torcs. So, as discussed in a previous blog, can we be certain that torcs were made from coins? or could alluvial, or indeed mined, gold be a source?

Travelling torcs.

The origin of the gold links to a further issue in gold studies: the assumption that all gold artefacts travelled from making sites in the south to the north.

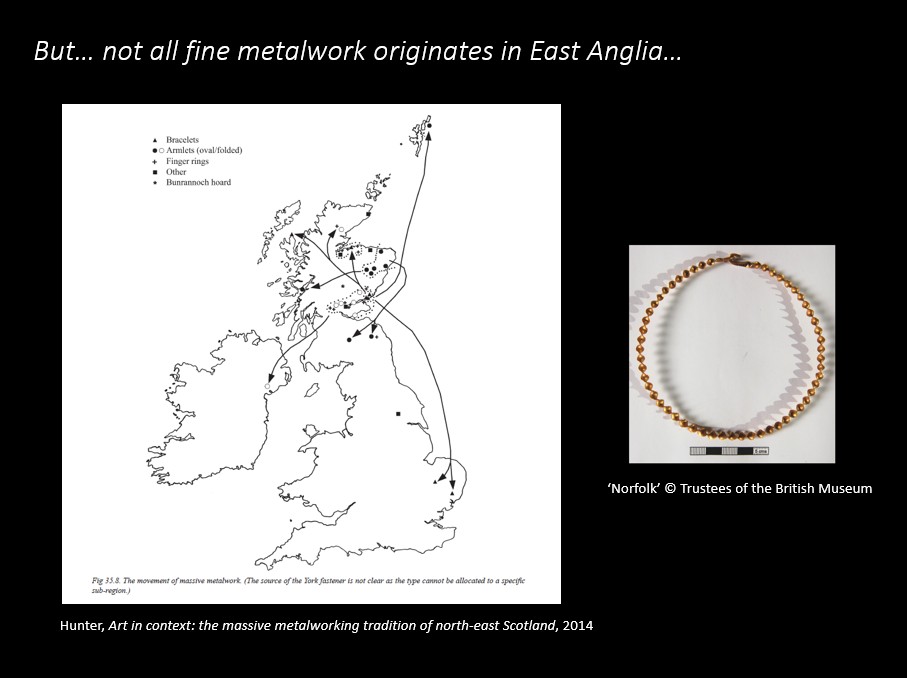

As can be seen above, the idea that gold artefacts moved from south to north has been around for a long time. However, with no evidence of southern workshops, or indeed any workshops for working gold, can this certainty be justified?

If we look at fine metalwork from Scotland, we can see that several items, torcs included, which have a known, and very discrete, origin in Scotland have been found in the south, even in the torc heartland of East Anglia. So could this be happening with torus torcs, also?

If we look at the Newark and Netherurd (here turned into a complete torc so people have a chance to admire how magnificent it must have once been) torcs we know that these two torcs were made or finished by the same hand and yet were found some 200 miles apart. Despite the fact that the Newark torc may have been moved from its original place of deposition there is no suggestion that either torc came from the south.

In addition, the identification of a further torc from Hoard H at Snettisham, which shows similar motifs to those seen in the Newark and Netherurd terminals, appears to have been made or finished by the same hand. As such, this could suggest the H.7 Snettisham torc is an import to East Anglia, rather than an indigenous southern example.

I now want to look at four case studies, where craft insights have altered the standard theories about torcs.

Case study 1: Concentric circles must be cast.

This idea, although not published, has been discussed with me on several occasions as further evidence that torus torcs must be cast.

However, replication work, in sheet, by the late Ford Hallam clearly shows this not to be the case.

In addition, the creation of concentric circles using a non-Western, exterior working technique, has shown that the reliance on Western working techniques and terminologies is not to be advised.

Ford’s replication also showed that the evidence of working seen on the interior of the Netherurd terminal best matches that produced by the use of the uchidashi technique. This interior evidence can also be seen on the Clevedon and Near Stowmarket torc terminals.

Case study 2: The Clevedon terminal.

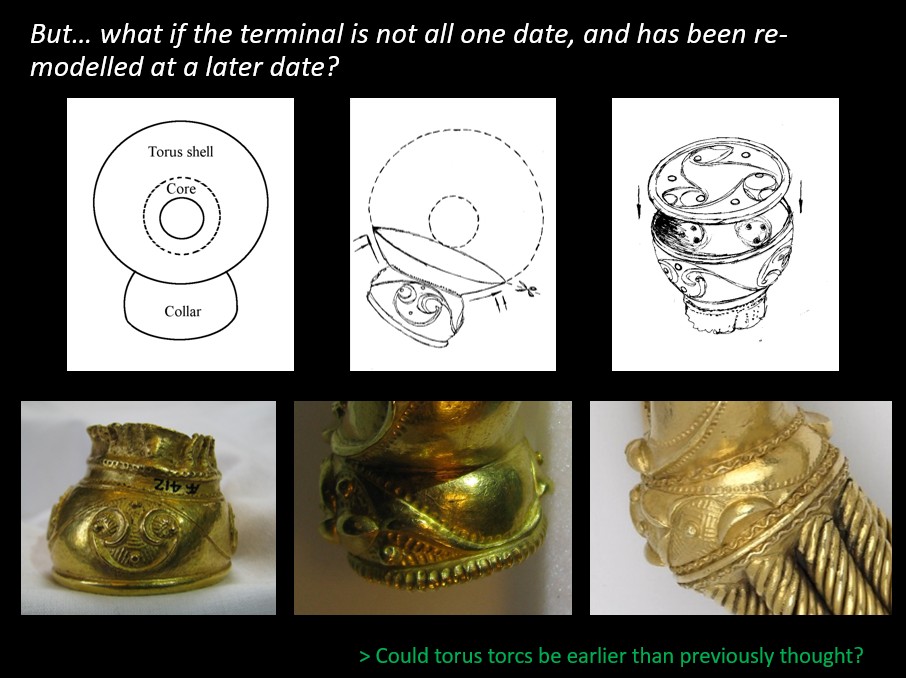

The Clevedon terminal has long been cited as an example showing the longevity of ‘Celtic art’ styles.

However, an examination of the Clevedon terminal has suggested an alternative explanation:

This would suggest that the Clevedon terminal was originally the collar of a torus torc similar to the Netherurd and Snettisham Great torc, which was cut down and reworked at a later date. This explains the earlier and later art styles as being representative of an earlier and later working and re-working of the torc. Such evidence adds to a growing corpus of torcs which have been re-worked and re-modelled over time. One such torc that this may also apply to is the Snettisham Great torc.

Case study 3: The Snettisham Great torc.

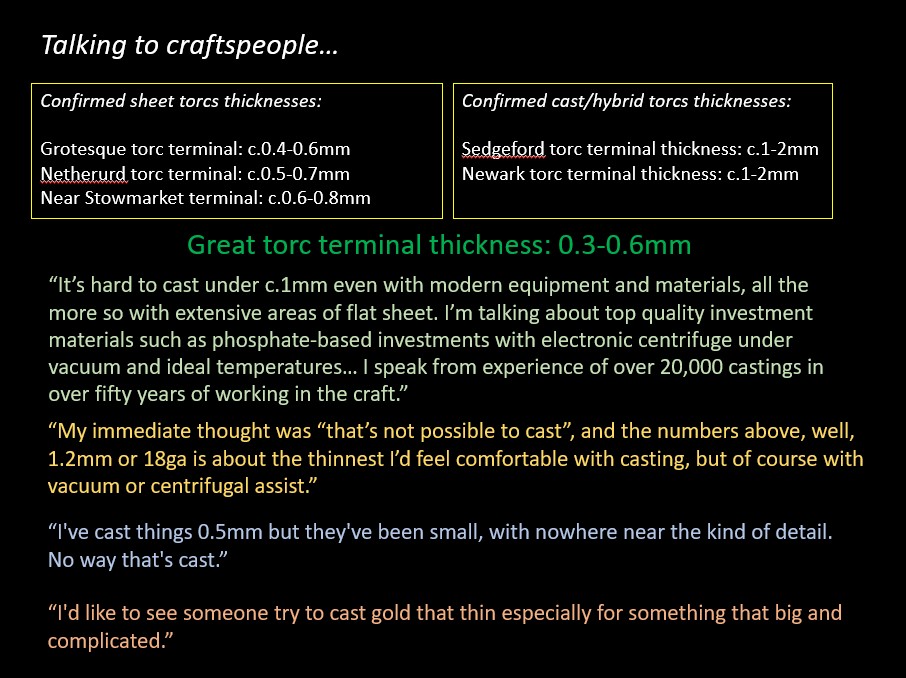

In the recently published Snettisham volumes, there are a number of issues that I have identified which point to a lack of understanding of the goldsmithing process. The Great torc, in particular, is described as being of a composite sheet/cast hybrid construction, with a sheet/hammered core and cast torus shell.

However, there is little evidence for this assumption, with typical features of a sheet terminal construction being present on the torc:

In addition, the thickness of the terminal alloy, at only 0.3mm to 0.6mm is well below that which could be cast, even using modern methods.

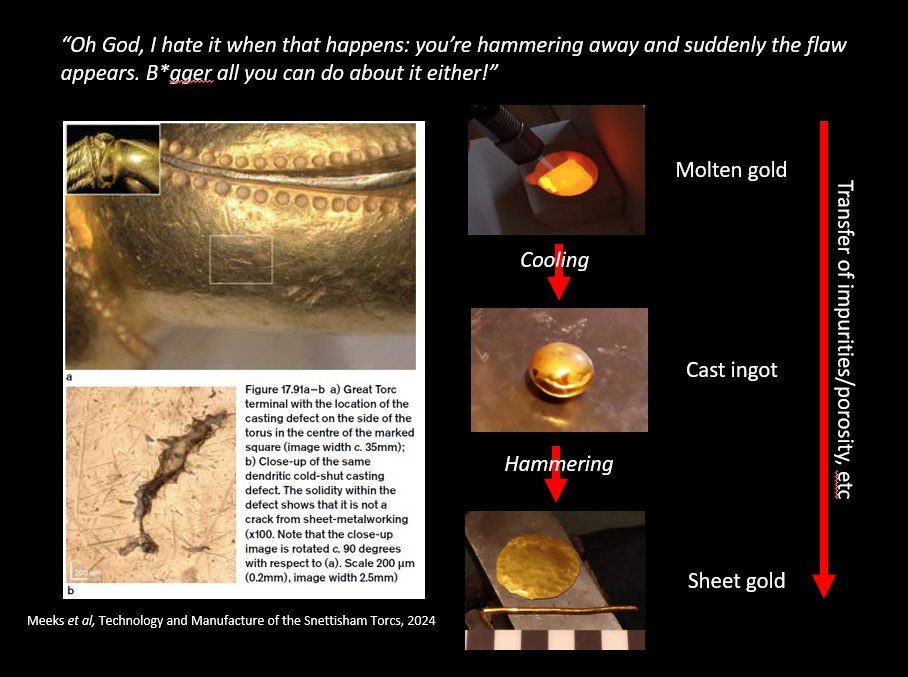

The interpretation of a cast terminal shell appears to originate from the finding of a small casting defect in the shell of one of the terminals. However, an understanding of the alloy working process, where a casting porosity can transfer to a sheet artefact does not appear to have been recognised. As such, there is no evidence that the Snettisham Great torc is cast, but much to suggest it is made from sheet/hammered gold alloy.

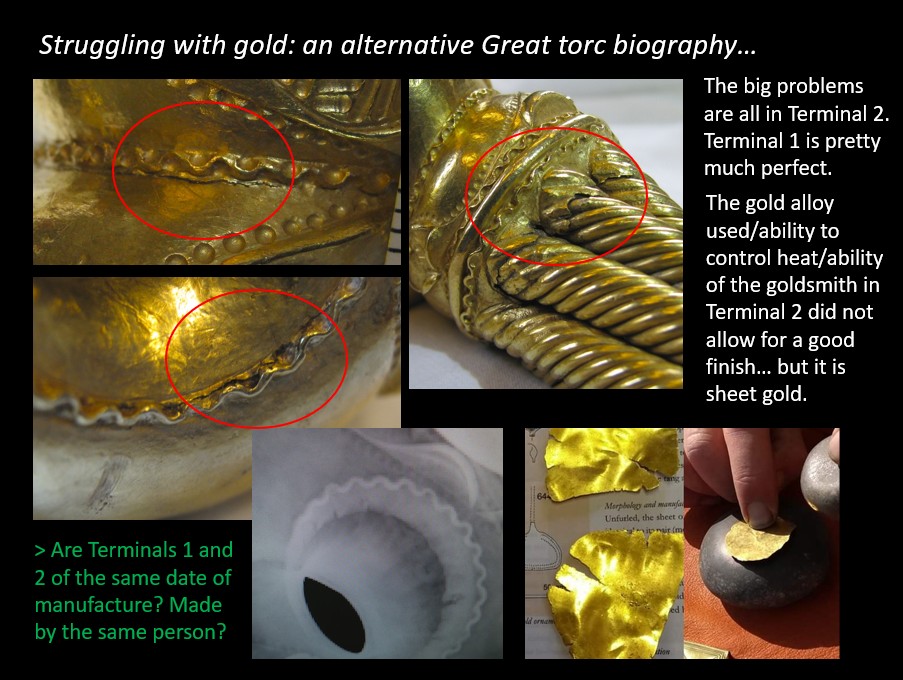

The understanding that the Snettisham Great torc is made from sheet/hammered gold along with a close examination of the manufacture, decoration – and faults – of this torc opens up an alternative biography. In this scenario, the terminals appear to have been made by two different makers, using differing quality gold alloys, and decorating each torc in an identifiably unique way.

This chimes with the evidence of the Clevedon terminal – which appears to have been repurposed as a new buffer torc terminal – and of the Netherurd terminal, which has been carefully removed from its neck ring (dents on the terminal end show that it was once attached to one) and which was perhaps intended to have a new neck ring and terminal as part of a reworked torus torc?

Case study 4: Hoard L from Snettisham.

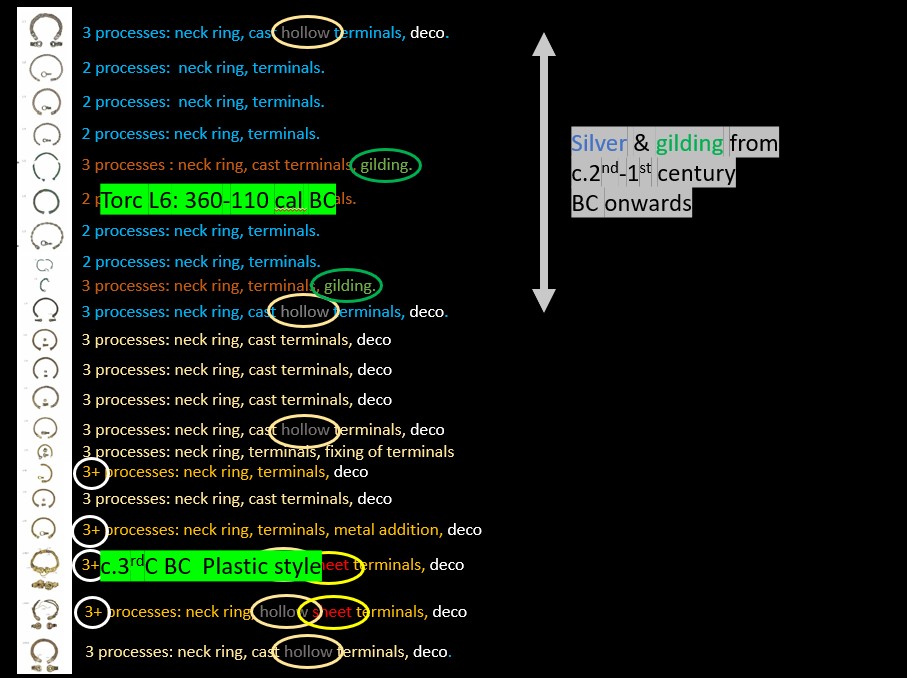

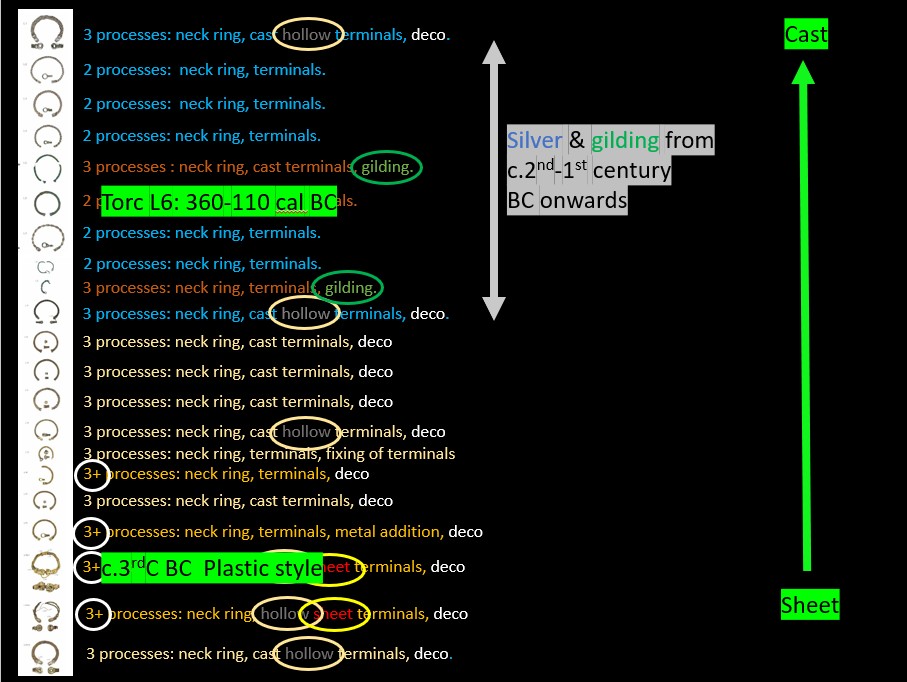

My final few slides are about how a craft perspective can perhaps give us, more widely, an alternative view on the Snettisham material, using the Hoard L torc deposit as an example. Hoard L comprises twenty-one torcs buried in two deposits (the upper deposit of torcs L.1-L.7, the lower of torcs L.8-L.21) separated by a small soil horizon, but apparently within the same larger pit.

The torcs are shown below, in order of deposition, with L.1 at the top, as the last deposited, and L.21 at the bottom, as the first deposited. The famous Grotesque torc, L.19, was the third torc added to the lower deposit.

I have colour-coded the torcs by dominant metal in each alloy, with blue for silver, rust for copper alloy and yellow for gold alloys, with a darker yellow signifying a richer gold alloy than that seen in the lighter yellow colour-coded examples. This follows the alloys identified in the Snettisham volumes (Farley & Joy 2024, Fig. 23.5). I have also identified if the torc terminals are cast, sheet, decorated, gilded and/or hollow and have given each torc a simplified number of processes used to make each torc: cast terminals, hammered wire terminals, the making of the wire neck-ring and decorating each count as a single process.

The manufacture of separate sheet (and some of the hammered wire) terminals involves multiple processes of manufacture and soldering/bonding, etc, so these terminals are classed as items that involve more than one (1+) process to make. Although not precise, this classification allows a general grouping of the torcs, according to whether they use two, three or more than three manufacturing processes.

As can be seen above, in general, torcs with more complicated manufacturing processes cluster towards the base of the hoard, with less complicated torcs found in the upper levels. However, please note the top, and final, torc in the deposit, L.1, has a more complicated manufacturing method if compared to those others in the upper deposit.

It can also be seen that torcs with hollow terminals, whether cast or sheet made, concentrate in the lower part of the hoard. Again note torc L.1, the only hollow terminal torc in the upper levels.

Sheet torcs are only to be found in the lower level of the hoard, although torc L.21, the first deposited torc in the hoard, is cast. Torcs not identified in the list as cast or sheet, have hammered wire or overcast wire terminals.

Gilded, in this case mercury gilded copper alloy, and silver rich alloys are only to be found in the upper levels of the hoard as a whole, although interestingly, they can be found both in the upper, and lower, separated deposits.

Current knowledge would suggest that the common use of silver and gilding only starts in these islands from around the 2nd to 1st centuries BCE. We also have a radiocarbon date for torc L.6, which would fit within this parameter. Additionally, the ‘Plastic’ art style of the Grotesque torc (torc L.19) would suggest a possible 3rd century date for this torc, at the lower level of the hoard.

My previous work has suggested that there may be a transition from sheet to cast working, with cast ‘copies’ being made of ‘original’ sheet/hammered torcs. This would seem to fit with the Hoard L finds, with sheet torcs only being found in the lower levels of the hoard. As such, taken as a whole, by looking at alloy type, manufacturing process, radiocarbon and art historical dating evidence it would appear that those torcs at the base of the entire hoard could be seen to be older than those in the upper levels.

However, this assumption does not necessarily apply to torcs L.1 and L.21 which appear out of place in this sequence. Although this oddity has been recognised by Farley & Joy for torc L.1, and the upper torcs of several other Snettisham hoards (Farley & Joy 2024, 592), the possible addition of torc L.21 as an ‘out of place’ example might suggest that the torcs in the bottom AND top of each hoard were of particular significance.

This analysis would also suggest that the hoards, irrelevant of the number of deposits in each pit, should be looked at very much as a whole. The red horizontal line separating the upper and lower deposits of Hoard H (see above), does not seem to have relevance to the deposition pattern of the torcs within the hoard as a whole, with upper torcs of the lower deposit fitting in well with those of the – albeit soil-separated – deposit above.

It would also suggest that, top and bottom torcs perhaps excluded, within the bulk of each hoard, older torcs were placed at the bottom, with successively younger torcs placed on top. As such, by looking at where they appear in the deposition sequence, it may be possible to date these torcs much more accurately than we can at present. Should we maybe be looking at each torc as representing a generation of around 20-30 years? Could each torc then have been linked to a specific person, or familial/group generation?

It would also suggest that we should be perhaps looking at the Snettisham hoards as buried lineages or ancestries: the long curated/collected/looked after symbols/status items of perhaps a community, family or group that were buried in one episode after their use above ground was no longer deemed necessary or required. This idea fits with the previous work I have carried out on the Grotesque torc.

The above is very much a work in progress, but the patterns identified above also seem to apply to several of the other Snettisham hoards – these hoards (top and bottom torcs excepted) seem to grade from sheet/hammered, decorated and more complicated gold torcs in their lower levels through to less complicated silver/copper alloy and gilded examples in their upper.

There is also a suggestion that hoards, such as Hoards G and H, have less extended lineages than Hoard L, with the majority of torcs deposited being made of – later – copper alloy and silver (see Fig 23.5, Farley & Joy 2024). I am currently looking in greater depth at this possible phenomenon, and its implications, and it will be the subject of an upcoming paper I am currently working on.

In the meantime thank you to all the goldsmiths, silversmiths and jewellers I have worked with: here’s a few of them and their work!

…it’s good to torc!

References

Farley, J. & Joy, J. (eds) 2024. The Snettisham Hoards. British Museum Research Publication 225, London: The British Museum Press.

One Reply to “”