By Tess Machling

[A download/print PDF version can be found at the end of the paper]

‘My members don’t want to be quasi-archaeologists, they want to go out on a Sunday, dig around, get dirty, find something good’

John Wells, the Association for Metal Detecting Sport in oral evidence to the All Party Parliamentary Archaeology Group (APPAG) Inquiry on Archaeology and Metal-detecting, 26th June 2025.

Abstract

My previous work has discussed various aspects of the hobby of detecting: how the context of archaeological finds is often lost, how private ownership of finds is reducing the archaeological dataset, how our obsession with monetary worth may be fueling an increase in artefact theft and, more recently, the hidden and unacknowledged costs of the hobby of detecting to the wider British public.

This work has looked at England and Wales only, and so these observations do not include the costs incurred in Scotland. In Scotland, 6000-8000 finds are reported to the Scottish Treasure Trove Unit every year, and it should be noted that the increasing ‘reward’ sums (£138,651 was paid to Scottish detectorists in the 2024/2025 period) and associated administrative costs are significant additional costs to the England and Wales figures that I have been working on.

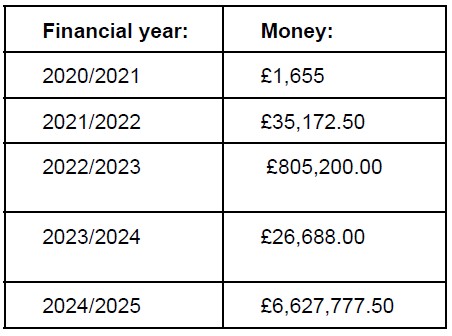

This blog brings the current work up to date, with new information received from Freedom of Information requests submitted to the Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) and to the British Museum, which were returned in December and January 2025. These figures have never before been publicly available and provide the only absolute costings for the amount paid out in ‘Treasure’ rewards since 2020. I have also included information from the latest, 2024, Treasure Valuation Committee (TVC) minutes, which were published in early January 2025.

The overall picture is shocking – tens of millions of pounds worth of costs are being incurred by the British public (via government funding, funding bodies, individual donations, crowdfunding and museum payments) and tens of thousands of artefacts are being lost: metal detecting, rather than being a harmless hobby, is in fact a huge drain on the heritage resources of England and Wales.

I would argue that it is now time for further regulation of the detecting community and, at the very least, for the detecting community to start contributing to the costs incurred by their hobby. That money is certainly available, with the National Council of Metal Detectorists (NCMD) adding tens of thousands of pounds each year to their £600,000+, self-described, ‘Battle Fund’ war chest. With over 80,000 detected artefacts being found every single year in England and Wales, this regulation cannot come soon enough.

Hidden costs

The hobby of detecting places a large burden on the public purse. However, the precise cost is difficult to quantify. The only two fixed figures that we have is the amount paid by DCMS (£1.4 million grant-in-aid to the British Museum) to fund the scheme, and the ‘reward’ payments (£7.2 million in 2024/2025) made to finders and landowners. But beyond this £8.6 million current annual figure, there are many other – more hidden – costs.

Although the DCMS grant-in-aid funding to the British Museum contributes towards the salaries of the Finds Liaison Officers and Finds Liaison Assistants, their salaries are also significantly supported by funding from partner museums, Historic Environment Record centres and councils etc. A number of internships are funded by the Headley Trust and the Worshipful Company of Arts Scholars. As such, I suspect the £1.4 million is probably much less than half of the day to day costs of administering the PAS.

In addition, the Coroner’s work during the Treasure process is funded by government and the Treasure Valuation Committee members do not take any remuneration for the increasing number of hours they work for the PAS.

In the field, excavation and other weekend and out of hours work, by FLOs and other archaeological professionals/academics is largely unpaid (beyond a few hundred pounds contributed by the NCMD) and, in the case of finds which need specialist conservation treatments, the cost is usually picked up by the archaeological community and/or government or charitable organisations (for example, the recent Melsonby hoard, where Historic England – another DCMS grant-in-aid body – gave over £120,000 to the excavation and initial conservation of these complex deposits. The £250,000 amount to buy the find has been achieved by grants and public donations, but the fundraising for ongoing conservation and display has yet to be realised). As I’ve previously written about – via public donation and crowdfunding, philanthropic benefactors and government, museum or charitable funds – treasure ‘rewards’ to finders and landowners are also paid for without contribution from the detecting community.

In the longer term, preservation, conservation, curation, display and security charges are met by the acquiring museums. Again, there is no financial input from finders, landowners or the wider detecting community. In short, we – the British public – are paying, by one route or another, both the reward to landowners and finders and for the administration, excavation and ongoing costs of PAS finds.

The real cost of ‘Treasure rewards’

Having previously done a very rough, ‘back of fag packet’, adding up of all the ‘rewards’ recommended by the TVC in any one year, I had come to the following figures and, with the publication in January 2026 of the TVC minutes for 2024, I have been able to update these to include 2024. The 2024 figures, although lower than 2023, still show an upward trend in amounts since the time of Covid which echoes the increasing numbers of detectorists taking up the hobby since then.

- 2018: £571,000

- 2019: £1,003,000

- 2020: £150,000

- 2021: £998,000

- 2022: £2,016,000

- 2023: £7,172,000

- 2024: £4,285,000

However, my adding up was very much an approximation and so, in November 2025, I submitted two Freedom of Information (FOI) requests: one to DCMS and the second to the British Museum. In these, I asked for the total amount of money paid out, each year, to finders and landowners for the years 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024. But why FOIs to these two organisations?

Who pays for what?

‘Treasure reward’ payments are administrated by two bodies: DCMS and the British Museum. As the FOI response I received from DCMS says, both organisations ‘invoice the acquiring museums, hold the reward payments in a suspense account and then pay them on to the finder and landowner.’ Money in, money out. As such, these amounts do not appear in the accounts for either organisation and so a FOI was apparently the only way of getting hold of them.

DCMS handles any funds for ‘Treasure’ acquisitions made by the British Museum and the British Museum deals with acquisitions that involve any other English and Welsh museums. There are occasional exceptions where the British Museum has initially shown an interest in acquiring finds, but then pulled out and the finds were then bought by another museum. As such, in the figures below, the £4.3 million paid for the Chew Valley Hoard was included in the 2024/2025 DCMS figures as the British Museum had initially expressed a wish to acquire the hoard, even though it was the South West Heritage Trust who eventually bought it. As you can see, much to my dismay, my ‘back of fag packet’ adding up really wasn’t that far off the mark!

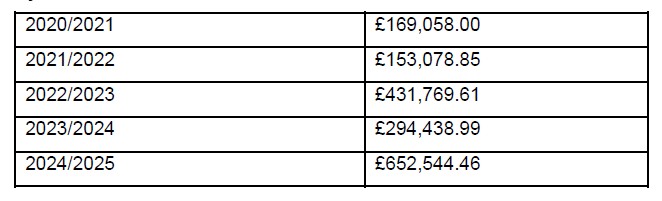

For the British Museum, despite initially refusing my FOI request, I requested an internal review (which was carried out by the Finance Director of the British Museum) and my request was granted and the figures released:

The total amounts paid out in rewards to finders and landowners, per financial year, by DCMS and the British Museum are therefore as follows:

- 2020/2021 £170,713

- 2021/2022 £188,251.35

- 2022/2023 £1,236,969.61

- 2023/2024 £321,126.99

- 2024/2025 £7,280,321.96

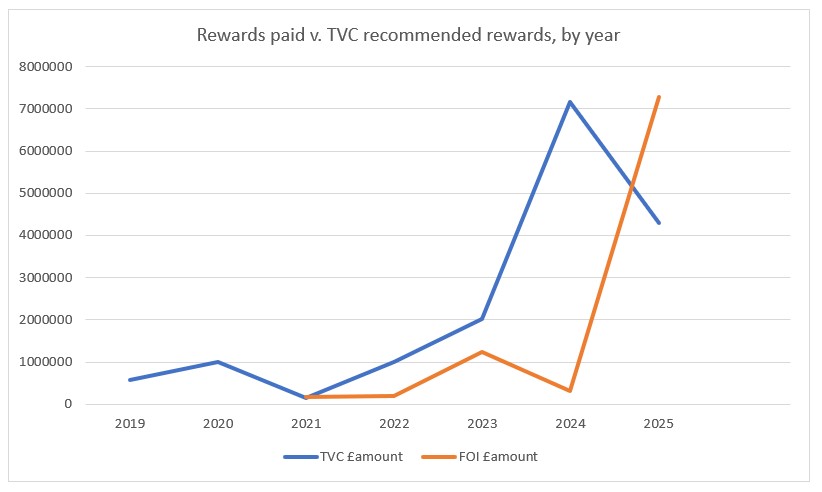

I have plotted the TVC recommended reward totals, against the annual amounts paid out by DCMS and the British Museum. It should be noted that there is a slight lag in numbers, as the TVC minutes work on a calendar year and their committee decisions are made before ‘reward’ payments are made, whereas the DCMS/BM FOI figures are actual payments made in each financial, April to April, tax year. As such, the FOI data slightly lags behind the TVC data, but the trends are very clear.

Although, there is variation each year, the upwards trend of the last few years is clear, with £9,197,382.91 having been paid out in ‘Treasure’ rewards since 2020. However, it should be noted that a large portion of this figure was spent in 2024/2025 and – despite the inclusion of the £4.3 million Chew Valley hoard in these numbers – the TVC minutes figures for 2024 of around £4,285,000 would suggest that the trend for excessively high reward payouts will continue into 2025/2026 and beyond.

These multiple £million payouts dwarf the £1.4 million paid to run the Portable Antiquities Scheme each year and also represent a loss to English and Welsh Museums who paid the £7.3 million rewards in 2024/2025, and who will face a further annual bill of £4.3 million in 2025/2026. These are huge figures and represent the equivalent of hundreds of curator or FLO salaries. This does not have to happen: if finders/landowners waived their rights to rewards, as archaeologists do, those same finds could have gone to the museums anyway, and the monies saved could have been spent elsewhere to support the museums involved.

It must also not be forgotten that this is just the reward costs, and does not include the cost of administrating PAS or the other hidden costs to museums/HERs/the wider heritage community who give their time, resources and expertise unpaid to supporting this creaking system.

The TLDR bit.

I wanted to end this blog summing up the ‘Too Long Didn’t Read’ figures for everything I have been doing over the last few months. Afterall, the financial cost is not the only element in this picture:

1) Only c.4000 (less than 1-10%) of the 40,000 to 420,000 detectorists in the UK are recording their finds with PAS.

2) ‘Treasure’ case numbers are rising by at least 10% a year. How many are not being declared?

3) The recorded numbers of non-‘Treasure’ finds are rising by thousands each year, but it may be much higher if we include finds that are not being recorded by PAS (N.B. recording with PAS is voluntary).

4) Of the less than c.4% of ‘Treasure’ finds donated to museums, almost none are detected finds.

5) c.50% of ‘Treasure’ finds wanted by museums are subsequently disclaimed as museums struggle to find funding to pay for them.

6) Only c.25% of Treasure finds are being bought by museums.

7) Treasure is currently costing us, the British tax payer – via grants, crowdfunding, museum funds – at least £7 million a year.

8) From export records, c.6% of ‘Treasure’ finds are being exported from the country.

9) c.80,000 recorded non-‘Treasure’ finds and c.1000 (75%) ‘Treasure’ finds a year are being handed back to finders and landowners to do with as they wish: they can be sold on, given away…or even destroyed/melted down. This is entirely legal.

10) Of the c.80,000 – perhaps hundreds of thousands – of finds detected each year, at least 30% are taken out of the country/exported overseas.

If you want to read how I have come to the figures above, the precise workings can be found in the blogs HERE, but I reiterate again: we are now in a position where the portable heritage of the country is at dire risk and if we don’t act now to legislate the hobby of metal detecting, it will be too late.

It is time for the archaeological community – and the responsible detecting community – to act.

For ten years I’ve offered the results of all my research for free and open access. I’m an independent researcher and have no funding, so all museum trips, research visits, writing up, conferences etc are funded by my scraping together savings and lecture fees etc.

Thanks to a few recent changes in circumstance, this is getting more and more difficult for me to fully support and, even though I’ll still be doing everything open access and always will, if you do have a bit of spare cash (…and really only if!!) buying me the occasional ‘coffee’ to support my gold research would be really fabulous. You can buy me a ‘coffee’ here!

I don’t know of any other country that has such an insane system. Instead of bankrupting the museums, the money spent trying to retain the artefacts found through detecting should be spent on museum programmes educating the public about how valuable their shared heritage is.

If I go to the national museums in other countries, they are filled with objects from their own country. They proudly display their heritage and history. It’s all about them. But there is no “British museum” There is no national museum dedicated to the history, prehistory, and culture of Britain.

In the big museums relatively little space is given to British objects compared to the space displaying objects from other nations. I wonder if that doesn’t make museum visitors think that the archaeological material culture of Britain is not that important, and that preserving the UK’s shared public heritage takes a back seat to the exotic objects collected from other cultures. Where is a country left when there is no respect for its culture? Other countries are working hard to repatriate looted objects or objects that were excavated while colonised. It’s not because the objects are a commodity, but because the objects are part of their collective history and cultural identity. It’s part of who they are as a society and a culture. Meanwhile in the UK, cultural heritage has become a commodity for anyone who is able to find a bit of it. Rather than feeling that they found something that should be shared with their community and contribute their finds to public museums, the objects are effectively held for ransom. If the public can’t pay, then they will find someone who can. Sadly, Britain’s heritage is reduced to a £ symbol in a get rich quick scheme.

LikeLike

Exactly this. Thank you so much for horror wise words

LikeLike

Great idea , tighten up the laws on metal detecting and ask the finders and land owners to waive their rights and simply hand over anything they find so the museums can display the artifacts and then make money from people coming to see them , it’s so easy to point the finger and say detectorists are stealing our heritage ,but they’re doing it by paying out hundreds and sometimes thousands of pounds for their equipment , then paying for the privelage of going onto someones land in all weathers and actually doing the leg work to find this national treasure in the first place . As you’re including the unseen costs in your calculations don’t forget the unseen costs incured to the detecting community too . My vehicle that i need to get to digs doesn’t pay for it’s own maintenance , mot or tax .I also need to pay for public liability insurance without which i am not allowed to go onto land and discover anything . Every bit of land in the UK is owned by someone ,there are no common land areas where anyone can go and find something of importance and hand it over to a museum for display purposes , even if they wanted to . The crown owns thousand of acres of land across the UK ,the Forestry commision , local councils and they all want the laws on detecting tightening up so they can make more money for themselves ,this isn’t about National Heritage it’s simply about money , take away all detecting rights and make it illegal and ban everyone from continuing with their hobby ,it will save Museums and PAS millions of pounds a year and all the items of National Importance will remain in the ground undetected because no one is willing to fund a mass survey of the land in the UK to find treasure ,but they’re quite willing to accept treasure that someone else has paid out good money for in the hope of finding something. Metal detecting is not a get rich quick scheme ,occasionally a hoard that’s worth thousande of pounds is found and it makes the headlines , but i’m yet to see the headlines where hundred of detectorists have been out this weekend in the rain and found nothing of value . Personally and i know a lot of other people that feel the same way ,enjoy getting out at the weekend on a dig , and we don’t go with the intention of finding treasure to sell but to simply find objects of interest , enjoy a bit of social interaction and some exercise . I do however have a suggestion , if the museums obtained permission for a dig ,arranged refreshments ,toilets and decent parking and made it a free event where all finds are handed over i would go along and willingly hand over my finds of National Importance, good or bad and the museums can do whatever they want with it , all the bits of barbed wire ,the old nails , horseshoes and bits of old tractor parts and general scrap that we all find everytime we go out .

LikeLike

It’s your hobby – people don’t get paid for their hobbies.

Also, if you’re in it for the history, activity and social life, then record everything that needs it and donate anything of historical importance. Easy!

The first principle of archaeology is preservation in situ – that way in years time, when we have better scientific techniques we may not have to dig at all to recover far more information than we can now…

LikeLike