by Tess Machling

[A download/print PDF version can be found at the end of the paper]

Abstract

The Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) – the detectorist-facing branch of archaeology – which provides the framework for the application of the 1996 Treasure Act is stretched beyond capacity: the Finds Liaison Officers (FLOs) who run the scheme day-to-day are few in number, underpaid, under resourced and often bullied. The wider system of Treasure determination and allocation is strained to breaking, with more and more finds flooding the system and time taken to determine the status of artefacts stretching into years.

Museums, who are expected to ‘acquire’ finds, do not have the money, time or staff to be able to do so and an increasing number of finds are being disclaimed, to be sold on at auction or taken into private collections, many of which may not even be in Britain and Ireland.

Detectorists are also increasingly unhappy and in every detecting group across social media there are comments which bemoan the inadequacy of the money they have been offered for ‘saving’ a find, or the length of time taken for finds to be examined/returned to them. Often there are comments by detectorists saying that they won’t bother recording any more.

The bottom line is that it is time for the detecting community to start realising the pressure that they are putting on an already overstretched heritage community and – as happens with the ‘polluter pays’ principle in developer funded archaeology – for them to start contributing towards the costs of their hobby.

Introduction

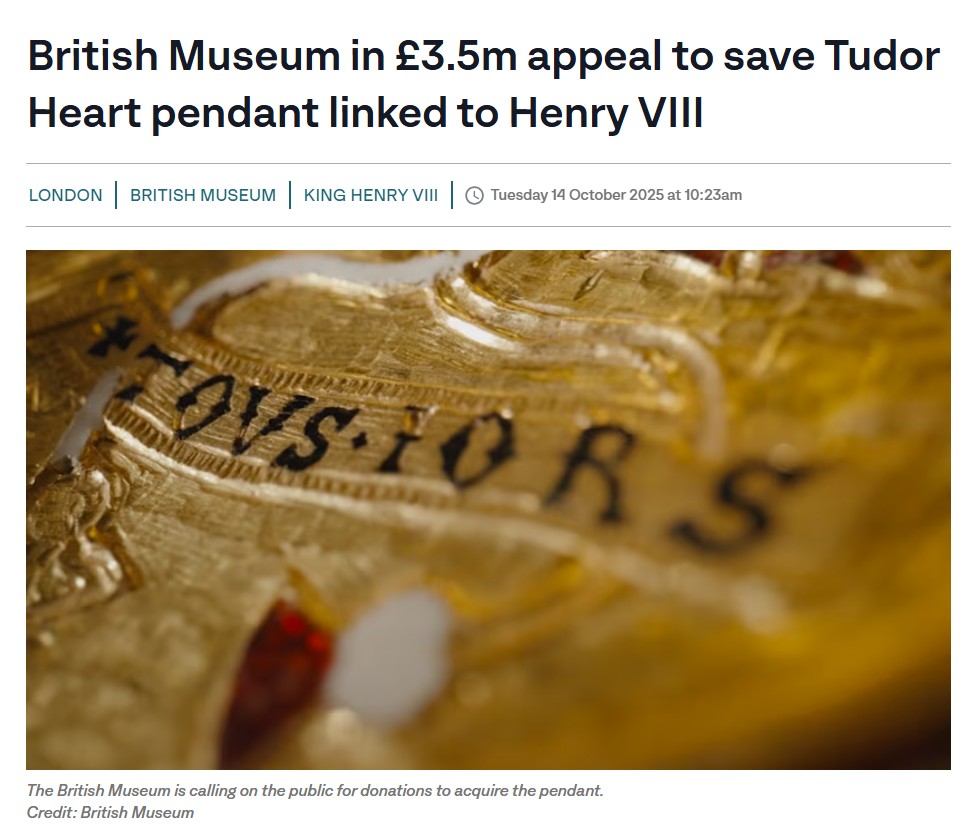

As anyone who reads my blogs or follows me on social media will know, over the last few years, I have become increasingly concerned with the 1996 Treasure Act (which covers England and Wales) and its implementation via the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS). A recently reported find of 15,000 Roman coins, excavated by the finder along with reports of a gold pendant valued at £3.5 million has given myself, and many others, further reason for concern.

Increasingly, monetarily valuable finds are making the news, but also increasingly, the public focus rests on the finder, not on the myriad of PAS staff, archaeologists, specialists, curators and others who are often overlooked in the process, and yet have the skills, knowledge and experience to place these finds in their true local, regional, national and international context. There is also little understanding amongst the wider British public of the costs involved in the scheme, and who foots the bill.

This blog is an attempt to gather together some of this information in an accessible format. I want to make a plea to all detectorists to think about their hobby and what they expect to gain from it: is the current system of state handouts to lucky hobbyists really justified? or, in an age of austerity, would it not be more patriotic to not accept a ‘reward’ and instead gift the shared heritage of these islands to museums, for the enjoyment of all, in perpetuity?

I think the case for the latter can be easily made. My personal view is that we should stop being anxious about offending the metal detecting community and that it is about time that we stood up for the heritage of these islands. I believe it is necessary to introduce a much stricter set of rules that not only make the detecting community pay towards the national costs incurred for their hobby, but also to regulate the use of detectors through some form of licensing. The continuing archaeological value of our shared national heritage requires nothing less.

In the beginning…

The rise of the metal detector, and the increasing unmanageable number of finds is only a relatively recent phenomenon. As a friend recently put it to me, there are three phases of archaeological engagement with detecting: the 1970s, when detectors (indeed any geophysics kit) were rare and engagement between archaeologists and detectorists was rarer still. Indeed it was not uncommon for archaeologists to ‘seed’ sites with drawing pins to discourage overnight looting and vandalism from some rogue individuals!

At this time detecting was a skilled activity and you could not just pick up a detector and use it, you had to know what all the various bleeps meant. As such, taken with the cost of the kit, there were relatively few who took part in the hobby. By the 1980s, archaeologists were starting to realise the potential of the detector on sites, and I remember in Sussex in the mid-80s, having detectorists sweep and mark a site before digging, and check spoil heaps for anything that might have been missed.

By the 1990s the detecting kit was becoming increasingly easy to use and the number of finds turning up necessitated the introduction of the 1996 Treasure Act, replacing the ancient common law of Treasure Trove, which had becoming increasingly unworkable. The 1996 Act established the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) and in 2001, 38,158 items were recorded by the scheme. In this same period archaeologists started to use detectorists more and more on site, with battlefield surveys being a notable example.

Throughout the 2000s numbers of finds continued to increase until Covid hit. During lockdown the hobby exploded, with many buying and using detectors for the first time. By 2023, over 70,000 finds were recorded in the PAS database in that year, and the rise shows no sign of abating.

Recent years have also seen an explosion in the number of detecting rallies: commercial ventures where hundreds (Detectival 2025 recorded around 1000 attendees, from 37 countries) descend on a known historic area for a weekend’s detecting. Supported by various online resources which identify the location of historic sites, and armed with the latest kit, there is less skill needed to be able to operate a detector and, as such, less skill needed to find something.

The PAS process.

In England and Wales, when a find is discovered by a detectorist it should start a process of reporting, recording and cataloguing which, in theory, adds to the archaeological corpus of these islands. However, with just under 4000 of the 38,000 – 100,000 detectorists operating in these islands (the National Council for Metal Detecting has 38,000 members as at April 2024) recording, these figures would suggest that less than 10% of detectorists are reporting anything they find.

After all, the reporting scheme – unless a find is Treasure, where legal obligations apply – is only voluntary. Indeed, the Department of Culture Media and Sport (DCMS) Participation survey of 2023/2024 found that 1% of adults in England had participated in at least one episode of metal detecting in the last 12 months. This suggests that those reporting their archaeological finds are, even allowing for those who may find nothing, hugely unrepresentative of the overall hobby. We can only guess at how much archaeological evidence is being lost by those who don’t.

In addition to the loss of contextual information, the nature of metal detection means that often only metal objects are located and, perhaps more importantly, unless a detectorist is knowledgeable in finds identification, what is reported will often exclude less obvious, non-metal, finds (and even with metals, lead and iron are often discarded in the field). Often detected finds will also have been cleaned, perhaps removing important organics/residues (as an aside, finders are given 14 days to report their Treasure finds and in my experience a lot of cleaning, handling and reshaping can happen within that time period…).

As such, very few non-metallic and/or associated finds, or those with adhering residues etc, ever reach the eyes of the Finds Liaison Officers (FLOs). This is clear in the PAS database, where only just over 5000 iron objects are recorded in a database of nearly 1.9 million finds, and – even allowing for the fact that organics are less likely to be preserved – only 125 pieces of leather. Whether the system could cope with the collection of all these other types of artefact is another thing entirely…

When finds come in to the FLOs, those finds are logged, identified and recorded within the Portable Antiquities Scheme database which contains the records of 1,843,216 objects (as at 25/10/2025) and which increased by approximately 70,000 finds during 2023. However, as I’ve talked about in a previous blog, although this database is useful to many researchers, particularly those looking at distribution patterns, for those who need to examine finds up close it has limited use.

Treasure finds.

In the case of Treasure finds (those of precious metal, or deemed to be of exceptional significance) the long process of identification, valuation, finder ‘reward’ and museum purchase starts at this stage. More details of this process can be found HERE. In some cases, and where detectorists are acting responsibly within the detecting code of practice, then FLOs and other archaeologists may be dispatched into the field, at short notice, to ensure the careful and archaeologically responsible excavation and recording of a find in situ.

In practice, media reports and social media platforms are full of detectorist’s finding narratives that often show fragile finds piled high next to muddy and deep holes, with no thought to the contextual archaeological evidence that has been lost in the process. If you want to see the difference in approach, watch this video and read this account of the finder digging up the Chew Valley Hoard, from Bristol, compared to the careful recording and archaeological excavation of the Seaton Down hoard from Devon. Both detected finds: one excavated and recorded properly by professional archaeologists, one thrown into buckets…

The reality is that careful excavation is not often happening, either because detectorists don’t report their find until it has been removed from the ground, or because FLOs, archaeologists etc are not available during the time when things are found. Although this may sound like a dereliction of duty by heritage professionals, when we look closely at the actual situation it is easy to see how this, often entirely preventable, scenario arises.

Finds Liaison Officers.

There are around forty FLOs based in various museums, Historic Environment Records (HERs) and councils across England and Wales. The PAS itself is funded overall by the Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), via a payment to the British Museum, who disperse the monies accordingly. It should be noted that the host organisations do not get paid for providing workspace for FLOs and many also contribute towards the salaries of FLOs. These costs of offices, calls, lighting, heating, etc are entirely borne by the host organisation. As such, via DCMS and museums and councils, we all – the tax paying British public – fund the running of the PAS.

The FLOs themselves are not paid well, with annual salaries of around £20,000- £30,000 being advertised. For this salary, they are expected to not only record PAS finds, but also carry out research, write reports, facilitate outreach and education and to manage and train volunteers and build up working relationships with detectorists, etc. Those partly funded by museums, etc also carry out work for the host organisation. Hours are long and many I have spoken to over the years are under resourced and bullied by finders when the FLOs are not available 24/7, or do not give the priority to individual finders that they feel they are entitled to receive. ‘We pay your wages’, ‘we are saving things for you’, ‘you work for me’ are all phrases I have seen time and time again in social media exchanges.

Of course, there are also law abiding, polite and respectful detectorists who make the FLOs jobs all that much easier, but that there is a significant proportion who aren’t is of grave concern. Indeed, if one hangs out in detecting groups on social media (as I do!), the complaints, insults and threats are all too obvious. Partly this comes from frustration at the overloaded system and its subsequent slow pace but there is also a significant proportion who are just blatantly rude and aggressive and have disdain for the work of the FLOs, archaeologists and those involved in the Portable Antiquity Scheme. There is often a sense of entitlement and ownership being projected by finders.

Within this maelstrom of poor pay, appalling workload and lack of respect, the FLOs do an incredible job: they are expected to be able to recognise any type of find from any period, to be able to research and record it accurately, and also to build up working relationships with detectorists within their areas. Not an easy job at all and one they carry out incredibly well. When you add in the extra responsibilities that the job entails (evening and weekend detecting club meetings, lectures and outreach, etc) this is especially hard. In fact, several folks I have spoken to estimate that their workload has increased at least five fold in the years since covid, when detecting really took off. It is no wonder that the turnover rate in FLOs is high.

[…and yes, over the many years, there have been a very few FLOs who have been less diligent and, very rarely, criminal, but these are exceptional cases which can, and do, occur in *any* profession. The majority are hard-working and efficient and carry out their roles with intelligence, integrity and speed. Could you identify, research and record upwards of 3000 finds, from many different periods, in a year?]

Within this background, when a detectorist finds something significant they are told to seek expert help. As detecting is usually an ‘out of hours’ hobby, significant finds (necessitating a professional response) do not usually occur within the working week, but rather in evenings, bank holidays and weekends, when the hobbyists are out, but the FLOs and archaeologists are trying to have a well-earned break.

It should be noted that there is not, as many assume, a special group of crack FLOs and archaeologists ‘on call’ out of hours, ready and waiting to receive an urgent summons to excavate treasure: whenever you read that archaeologists/FLOs have gone to assist in an emergency excavation, they are usually not being paid, or are given Time Off in Lieu (TOIL) which they are unlikely ever to receive as their day to day jobs are too busy to fit it in. Occasionally, as in the case of the Melsonby hoard, Historic England, or another such organisation may assist in costs.

But in short, they go and help out not because they are paid to (they usually aren’t) but because they love history and they don’t want to see it destroyed. Again, although there is a very small contingency excavation fund run by the National Council of Metal Detectorists, the costs are not borne by the detecting community, but by the archaeological workforce and/or their employers.

I have often heard tell of finders effectively blackmailing archaeologists into allowing finders to excavate something themselves: ‘the site is unsafe’, ‘someone will come and steal it’, ‘we can’t wait for you’, etc. But in almost all cases, it is a rare situation where a find cannot be safely reburied so that a well organised and staffed excavation can be carried out in due course. Also, FLOs and archaeologists deserve their time off from the day job. There are, of course, many responsible detectorists who do wait and we should applaud those who have listened to archaeological advice and resisted the urge to dig something themselves.

So when, as in several cases I’ve seen recently that shall remain nameless, detectorists expect FLOs/archaeologists to get out on site immediately – because a hole they’ve dug is now apparently exposed to public gaze and/or thievery – and then complain when they don’t, the fact that the FLO/archaeologists were unable to excavate a find was perhaps more down to the recklessness of the finders, rather than the laxity of the FLOs et al.

Rewards.

The Treasure Act of 1996 allows for finders to receive a ‘reward’ from a museum, which must not ‘exceed the treasure’s market value’. In practice this amount can be anything from a few tens to millions of pounds. Obviously, it will never be certain when high value objects may be found, and so it is conceivable that in any year, the total amounts paid out in England and Wales may range from a few thousand to many millions. If a museum does not buy a find, either because they cannot afford it, or does not want it, then the artefacts are ‘disclaimed’ (that is, handed back to the finder), and often sold at auction to satisfy the split of monies due to both finder and landowner.

In some cases, finders/landowners waive their reward and finds are donated to museums, however, in the latest Reported Treasure Finds 2022 and 2023 Statistical Release from November 2024, only 64 of the 1377 Treasure finds in 2022 were given to a museum for no/reduced cost. Also of that 1377, half (654 cases) were disclaimed, which means the artefacts were returned to the finder/landowner to do with as they wished, with no restriction on these finds being sold, gifted or even destroyed at any time in the future.

More and more often, the privately owned collections of detectorists are adding additional funding burdens to the archaeological community as they seek to preserve and make sense of uncatalogued display cases where very few records of what came from where and when survive, and where the collection owner is no longer available to pass on knowledge of their esoteric method. With the rapidly increasing number of private detected collections, this will only get worse.

High monetary value finds.

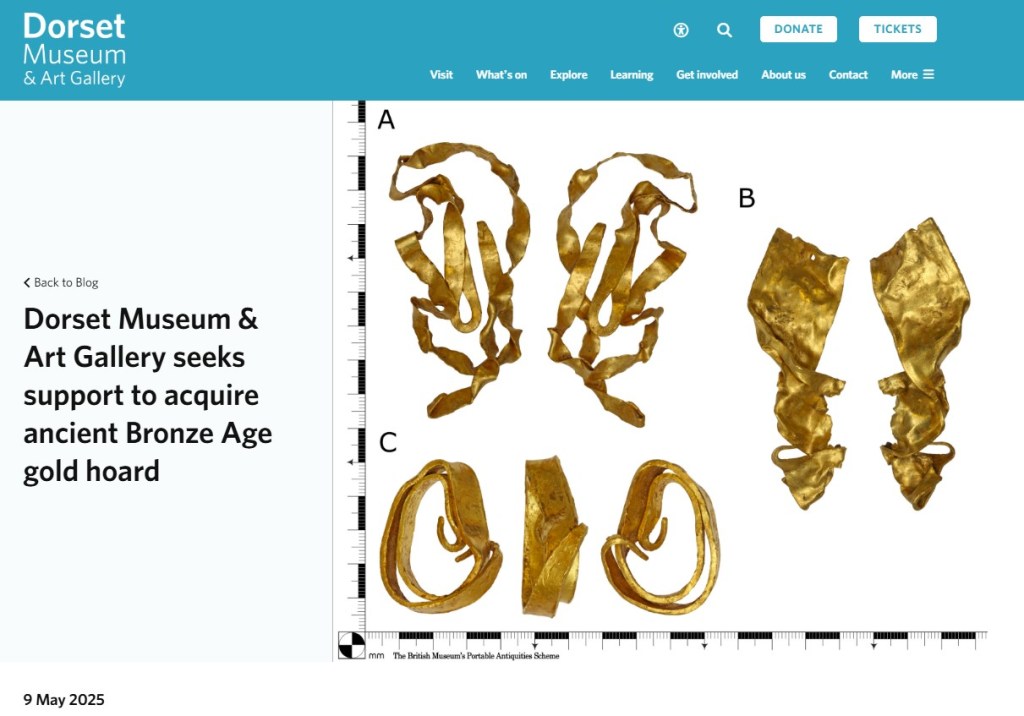

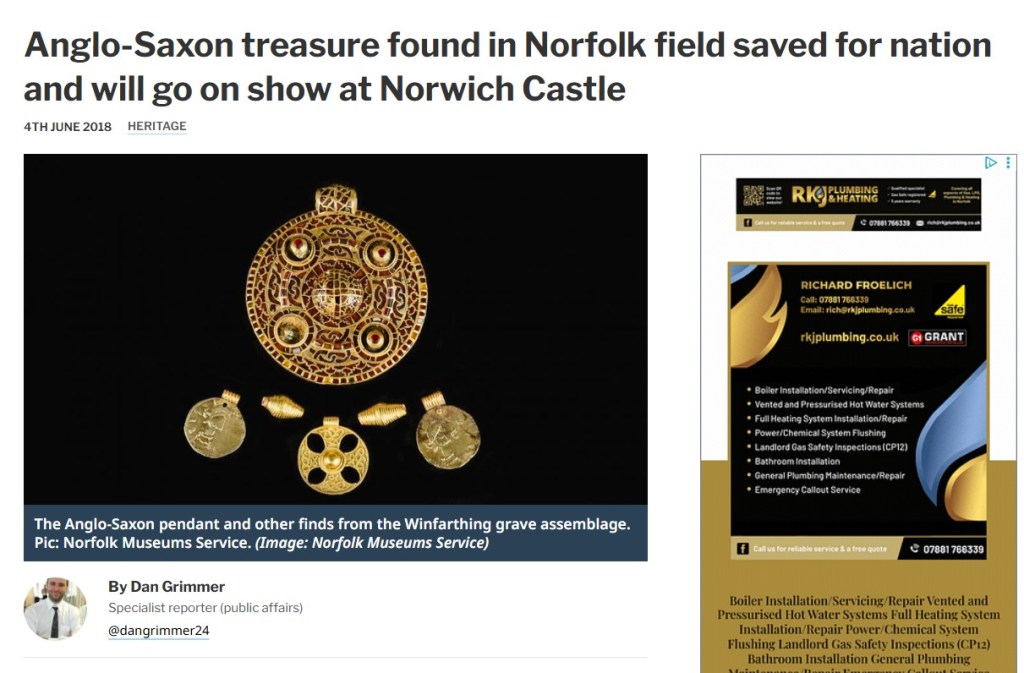

As the detecting community increases in size, and as detecting machines become more sensitive and easier to use, such high value finds are becoming more and more common, with recent ‘Treasure’ finds, for example, the Henry VIII linked gold heart pendant found in Warwickshire in 2019 having a £3.5 million price tag and the Frome Roman coin hoard valued at £320,000 . In the case of the Chew Valley and Seaton Down hoards, both hoards were only ‘saved’ for the nation when the individual finders – and landowners – were ‘rewarded’ for their finds: in the case of Seaton Down, £50,000 and for the Chew Valley Hoard, a staggering £4.3 million. This money went to the individuals who found the hoards and the owners of the land they were found on.

However, the annual Treasure cost figures likely do not reflect the current situation in 2025, with the only available data that I could find, and only for 2022, showing that £138,000 was paid out to finders/landowners. This report notes that there are always a number of cases yet to be determined (in this case, 239 of them) and it is likely that some of these will be high value cases where reaching a correct valuation, and thus ‘reward’, takes considerable time and research to achieve. As mentioned above, the total annual ‘reward’ cost is also utterly unpredictable, as we do not know when, or how many, significant, and costly, finds will arise.

As has been shown, the tax payer has contributed to much of the cost of administrating detected finds. The heritage community – museums, councils, HERs, archaeologists, FLOs etc – has also contributed much, in time and money to the cause. Where is the detecting community’s input, beyond a few hundred quid for the occasional dig?

Who pays?

Even before an artefact is deemed to be Treasure and the reward amount set, the next stage is for ‘collecting’ (those in the area where the object/s were found) or other museums to express a desire to ‘acquire’ the artefact or hoard. If no museum expresses an interest, within 28 days, it does not get taken to inquest. Museums have to do ‘due diligence’ on possible valuations before they express an interest, which also takes time and costs staff time. Should they wish to purchase the find, following valuation a three month (or four months if they are seeking grant funding) clock starts ticking. In cold terms, once the valuation has taken place (this stage can take many months/years to get to), the museum is invoiced for the find and has 3 to 4 months to pay up, or lose it forever.

The amount that the museum has to pay is set by the Treasure Valuation Committee, a group of museum, finds and archaeological specialists and antiquities dealers. The ‘reward’ that the museum ‘acquiring’ (fancy words that cover the sordid process that means museums hand over cash for history) has to pay goes directly to the finder and landowner. The ‘reward’ is not taxed: as the Capital Gains Manual so nicely puts it: ‘The rewards are pure gifts of cash’.

Despite this, social media detecting groups are full of complaints that finders have been ‘robbed’, that the valuation ‘is taking the piss’ etc. The attitude is that finders are entitled to cash for their hobby and that the system is trying to ‘rip them off’. Rarely do you see comments acknowledging that the ‘reward’ is a lucky gift, a gratuity buying back our national heritage from an individual.

In practice, to give these cash gifts, the museum will need to look to its own funds, apply for grant monies and, in most cases, crowdfund from their ‘Friends’ group, supporters and members of the general public. This all costs in staff time and museum resources at a time when museums are losing funding and staff. If the money cannot be raised, often the find is disclaimed. As the numbers of these cases rise, these appeals have recently become ever more regular and ever more frantic. Recent crowdfunding appeals include wording that suggests a find needs to be ‘saved’ (I found a lot of examples for this, of which this is just one…), that a find’s ‘future is at risk‘ unless funds can be raised, etc.

Increasingly, crowdfunding appeals are also asking for ‘stretch’ funds: money to not only buy the find, but to ensure it can be properly conserved, preserved, insured and displayed (each of these aspects has a significant cost in buying in specialist skills and services). Of course these meagre amounts will never provide for the ongoing costs of holding such objects in perpetuity, but such monies at least get the acquiring museum over the initial costs of an unexpected accession that needs to be looked after.

In reality, many museums in areas with high numbers of Treasure finds are now being forced to play ‘ip dip’ with our shared national heritage, to pick and choose which finds they can, and cannot, afford… and all to provide cash to those individuals who had the luck to find something while carrying out their hobby.

Who are we saving objects from?

Treasure finds often make the media, with reports of artefacts being ‘saved for the nation’, museums ‘running a desperate campaign’ to raise funds and numerous accounts of organisations launching urgent campaigns to keep artefacts ‘in public hands‘.

But what is rarely considered is who actually gets the money raised by these campaigns and it is, in reality, a very small number of people: the detectorists that found the object, and the landowner whose land it was found on. In effect we, the British Public, are giving huge amounts of money – tax free – to individuals so that we can buy back our shared national heritage.

Let that sink in: Our shared national heritage.

We are ‘rescuing’, ‘saving’, ‘securing’ (or however other many euphemistic terms we can come up with to cover the harsh truth) objects that tell rich stories about the past of these islands from individuals, because if we don’t they will sell them to the highest bidder (in the case of hoards, either as a lot, or more terribly, broken up from their original assemblage) keep them or perhaps even allow them to be melted down or destroyed.

We as a nation are being blackmailed, our history held hostage, until we cough up. I often hear people talk about patriotism, about pride in being English, Welsh etc and yet, to me, flogging the heritage of these islands (when you could gift it to a public museum to look after for the benefit of all of us) seems to be about as unpatriotic as it is possible to imagine.

The system is broken. So why are we not more concerned?

(If you’d like to support my work as an unfunded independent researcher, then please buy me a ‘coffee’. Thank you 🙂 )

I am a PAS self recording detectorist so do my bit and understand the recording process.

The system could and should change to reduce the workload since finds are not being handed over for recording by some detectorists due to the huge delays, and in some cases FLOs are not even able to accept new finds. The scheme could stop recording post medieval finds, which are of lesser research value, instantly reducing the workload and delays. Also apply some common sense to the amount of information recorded, no need to record the appearance and legends of medieval coins, instead just state their class, unless there is an oddity, or its a mule (front and rear from different pairs of dies). Indeed at times of over demand, just record the findspot, a photo and dimensions of a common find. Stop recording unofficial and undecorated/marked lead weights and ‘sack’ rings.

The general public have limited interest in archeology and at a time of hardship and cut backs will not want and can not be expected to pay for a PAS system that records just about every find to the detail archeologists want to.

I’ve would never sell an artefact. But change the law for those that do, simply make it illegal to sell any non-treasure artefact without a certificate of PAS recording, and charge £10 for such a certificate. This would raise money for more FLOs.

I always sign away my half of any potential treasure. If the finder and landowner both want to donate their half why not just record the item and offer it straight to museums without going through the treasure process?

Since the treasure system is overloaded allow FLOs the authority to declare a treasure item has not having enough historic value to merit being treated as treasure. I had a plain band silver ring go through the treasure process just for the valuation commitee to say because it was plain it could not be dated and was of no interest anyway. I currently have a very common restoration cuff link that no museum would ever want clogging up the process. Also instead of having a moving 300 year old cut-off date fix it at 1700 or better still 1600.

The database is also redundant in places. No need to record parish/region/etc since this can easily be looked up from the grid reference using freely available ordnance survey data. No need to record dimensions and weights twice, indeed duplicating data in a database is bad practice (I’m a computer programmer by profession).

LikeLike

From my point of view, as an artefacts specialist who needs to see things up close, the more we’ve got to look at, the better. I alai think the more data, the better. We do also need to record Post-med as the current eras ‘not worth it’ becomes so as history moves on. Bottom line is the system is overloaded and is underpinned by a sense of entitlement which needs to be changed. History is for all of us, not the individuals.

LikeLike

Hi Tess I did not say post medieval are not worth it, for instant I consider post civil war trade tokens with their local tradesmen names and trade has personally very interesting and important for local research, however in an overloaded system an imperfect decision has to be made on how FLO expertise can be used for the greatest increase in historical knowledge.

I used to be a state school science teacher and had to decide how best to allocate my time for the greatest benefit of my pupils, rather than attempt the ideal but impossible of regular individual tuition for all, or providing fully detailed rather than bullet list improvements for every piece of work I marked. In the end I gave up for my own mental health and to earn more for my own family, like many FLOs.

I also have the great sympathy for the toxic combination of underpaid, overworked FLOs and entitled detectorists (think of my time as an overworked teacher and entitled parents). In the end, like many FLOs, I foresake public service for my own mental health and to earn considerably more for my family.

There is another change lurking, AI is ideally suited to finds identification, indeed the first attempts at ‘AI’ systems 30 years ago were for visual identification. I believe the sizeable minority of entitled detectorists are only interested in their finds being identified and care not if they are recorded or not. When somebody trains an AI system on UK finds and makes it available for public use via a phone app, the entitled UK dectorists will just use this and never put their finds forward for FLO identification.

I think a big priority at the present should be to make this AI system a PAS one that can also imperfectly record what is presented rather than lose all sight of entitled dectorist finds. By the way I hate AI, but its enivitable.

LikeLike

Sorry Tess and FLOs,

I have just realised how rude and inappropriate my comments have been by not starting with a big thank you for the vocational dedication of FLOs and yourself in creating this website for the benefit of all.

I am ashamed of this creep into entitlement.

LikeLike

Again I disagree, if we keep allowing things to slip it will only get worse. We need to stand up for our heritage.

LikeLike

No worries. But yes, as archaeologists, none of us earn very much… and yet, we don’t demand payment for what we find.

LikeLike