[A download/print PDF version can be found at the end of the paper]

This paper can be cited as: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10629085

Those of you who have followed our work for some time will know that we aim to carry out, and share, our research in original ways. From independently peer reviewed papers to chocolate torcs, we try to find new ways to engage, educate…and entertain. For us, research isn’t worth doing unless the findings can be shared with everyone, and the excitement of releasing new discoveries to the world – and discovering what the world thinks – is what it’s all about.

Roll and I are lucky: as independent researchers without career ambitions to fulfil – or the requirements of an academic position or grant funding to comply with – we have the luxury of being able to experiment with output and ways of disseminating our work.

In this spirit we are releasing this pre-print paper today. Submitted for peer review and publication in January 2023, it is unlikely that this research will be publicly available for at least a year. This is not the fault of the people we are publishing with, but rather the academic system. These things takes time, especially in a world where most people are not paid to be editors, reviewers or indeed writers.

The other reason for pre-print publication on The Big Book of Torcs is so we can show you what this paper would have been, were we not restricted in the number of images we can use, or by the costs of image reproduction. Throughout the text, numeric figures (Fig. 1, 2, etc) are from the original paper, but the alphabetical figures (Fig. a, b, etc) are new. They are photos we would have included, if we could. In this pre-print we have also included photos alongside the original drawn illustrations, and hotlinks to museum catalogue entries.

We hope that you enjoy this paper and please let us know what you think.

Tess Machling & Roll Williamson, 23rd June 2023.

————————————————————————————————————–

Beyond Snettisham: a reassessment of gold alloy torcs from Iron Age Britain and Ireland

By Tess Machling & Roland Williamson

Abstract

Research by the authors (Machling & Williamson 2016; 2018; 2019a; 2019b; 2020a; 2020b & 2022) has shown new methods and techniques employed in the creation of gold alloy Iron Age torus torcs manufactured in Britain and Ireland. This paper pulls together the strands of this research and, together with recent analysis of decorative motifs, and comparison with other sheet or hollow torcs of the period, looks to place these torcs within a chronological framework, suggesting that ‘Snettisham style’ torcs may be of 4th century BC origin – an earlier date than has been previously assumed.

Background

Iron Age gold found in Britain and Ireland – that isn’t coins – occurs in a restricted range of items. Brooches are largely unknown until the immediate pre-Roman Iron Age (Hill et al. 2004) and bracelets/arm rings and finger-ring sized artefacts are rare, with only around ten simple finger rings and a handful of bracelets found. The overwhelming majority of gold finds are torcs – either neck or arm sized (Fig. a).

Figure a: The Snettisham Great torc (Image © The Trustees of The British Museum)

Until recently, the site of Snettisham in Norfolk – where the remains of c.310 torcs (60 complete (Joy 2018, 3) and c.300 pieces from c.200-250 others) have been recovered – has dominated the academic debate (Brailsford 1951; Cartwright et al. 2012; Clarke 1954; 1956; Fitzpatrick 1992; Garrow et al. 2009; Hautenauve 1999; 2004; 2005; Hutcheson 2003; Joy 2015a; 2016; 2018; 2019; Joy & Farley forthcoming; La Niece et al. 2018; Longworth 1992; Meeks et al. 2014;).

In addition, in the wider East Anglian region of Britain, a number of torcs have been recovered from Sedgeford (Brailsford 1971; Hill 2004), North Creake (Clarke 1951), Ipswich (Owles 1969; 1971; Brailsford & Stapley 1972), Bawsey (Maryon 1944), ‘South West Norfolk’ (Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery), ‘Near Stowmarket’ (Machling & Williamson 2020a) Middleton, Narford, Marham, and East Winch (Hutcheson 2007). Including Snettisham, c.400 torcs or pieces of, representing over c.330 torcs, have been recovered from East Anglia.

Beyond East Anglia, torc finds are less frequent – only around 50 are known from outside of this region. However, there are finds from as far afield as, for example: Clevedon in Somerset (Jope 2000, Pl. 120); Hengistbury Head (Bushe Fox 1915) and Spettisbury (Hawkes 1940) in Dorset; Glascote (Painter 1971), Needwood Forest (Hawkes 1936) and Leekfrith (Farley et al. 2018) in Staffordshire; Newark (Atherton 2016, Hill 2005) in Nottinghamshire; and Rawdon Billing (Whitaker 1816) and Towton (Joy 2010) in Yorkshire. In addition, the recently auctioned Knaresborough Ring from Yorkshire is believed by the authors to be a cut down piece of torus torc (BBC 2022). The Netherurd (Feachem 1958) and Blair Drummond (Hunter 2010, 2018) hoards and torc finds from Auldearn (Hunter 2014) and Deanburnhaugh (Fraser Hunter pers. comm.) come from the north, in Scotland.

Current thinking

With such a large concentration of material in East Anglia, it is no wonder that much research has focussed on this area. In his book, Early Celtic Art, Jope (2000) identified a ‘Snettisham style’ which he saw as being defined by hatched tooled panels, dummy rivets and ‘eccentric shapes defined by relief modelling conjured by dome capped trumpets and long curling curved leaves’ (Jope 2000, 84). He viewed the Snettisham Great torc, the Snettisham ‘bracelet’ – found attached to the Great torc – and the Netherurd terminal (Fig. b) as the pinnacle of this style.

Figure b: The Netherurd terminal (Image © National Museums of Scotland)

From the first findings of the 1940s (Brailsford 1951; Clarke 1951) to the present day (Meeks et al. 2014; La Niece et al. 2018) torcs, and especially the ‘Snettisham style’ decorated torcs, have been assumed to be of ‘very probably East Anglian origin’ (Meeks et al. 2014, 154) with those torcs that occur beyond East Anglia ‘travelling north through a process of gift exchange or diplomatic ties’ (La Niece et al. 2018, 415). This view has remained unchanged, despite the recent finding of many torcs, beyond the confines of East Anglia (e.g. Newark in 2005, Blair Drummond in 2009, Leekfrith in 2016) and the entire absence of any evidence (e.g. workshops etc) to suggest that there was gold-working going on within East Anglia in the Iron Age.

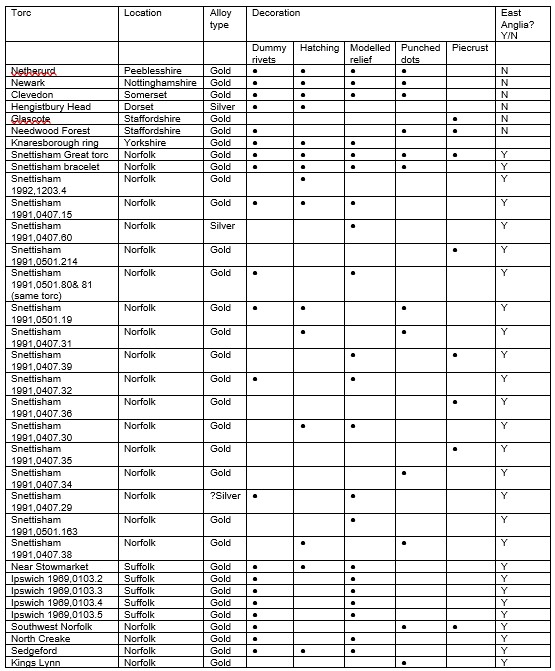

When counted, the number of identifiable ‘Snettisham style’ decorated torcs/parts of torcs recovered from across Britain is illuminating (Table 1). If gold, silver and copper alloys are taken into consideration, at first glance, East Anglia dominates. There are twenty-two examples from East Anglia (including Snettisham examples, five Ipswich torcs and the ‘Southwest Norfolk’ and North Creake torcs) whereas, only five torcs from beyond East Anglia (Netherurd, Newark, Clevedon, the Knaresborough Ring and Hengistbury Head) are decorated with at least one of the decorative elements identified by Jope.

However, when examples that show none of Jope’s ‘relief modelling’ are removed from the East Anglian total this becomes seventeen examples. Furthermore, if we look at only gold examples which fulfil each of Jope’s criteria, then there are only five examples from East Anglia (the Snettisham Great Torc and ‘bracelet’, the ‘Near Stowmarket’ piece and the Snettisham 1991,0407.15 and Sedgeford torcs) with four examples (the Netherurd terminal, the Newark and Clevedon torcs and the Knaresborough ring) having been found beyond East Anglia. As gold working, especially in the case of sheet, is a very specific craft, using different tools, methods and skills, it is reasonable to separate out high-quality gold torcs from the rest.

The authors would also argue that punched dots and piecrust decoration (where dots have been punched alternately to create a raised wavy line – Fig. c) should be included in the decorative motifs indicative of ‘Snettisham style’ as these regularly occur alongside the classic motifs identified by Jope, for example in the Snettisham Great torc and in the Newark torc. If this is the case, this would raise the East Anglian quotient by a significant amount, but would still not significantly alter the picture for high-quality gold torcs, which remain evenly represented both beyond, and within, East Anglia.

Figure c: Piecrust decoration on the Snettisham Great torc (Image © The Trustees of The British Museum)

Recent detectorist recovered finds, along with a research focus on material recovered beyond East Anglia, has led to new interpretations which have challenged the Snettisham focussed theories (Hunter 2010; 2014; 2018; Machling & Williamson 2016; 2018; 2019a; 2019b; 2020a; 2020b & 2022). It also needs to be remembered that any site of deposition is not necessarily the site of manufacture, either locally, or regionally (Joy 2019, 479). In addition, the burial of torcs, and other metalwork, across East Anglia might be the product of a society which valued deposition above other forms of expression (La Niece et al. 2018, 415). Such a scenario might mask an equal number of torcs in other parts of these islands that were perhaps present in the Iron Age, but which were lost to being melted down, recycled, remodelled, etc and so never appeared in the archaeological record.

It is also possible that another multi-hoard, Snettisham-type, site remains to be found in the UK and Ireland (Jope 2000, 81): just one site of this type beyond East Anglia would entirely alter the traditional view of East Anglian based torc making and, with increasing numbers of torcs having been found only in the last 20 years, this would not be unimaginable. It is also worth mentioning that many sites where torcs were found in antiquity have not been fully explored (Hutcheson 2004, 48).

Indeed, the site at Snettisham was thought to have been ‘virtually wrecked by ploughing’ (Stead 1991, 447) until the 1990/1991 excavations identified another nine previously unknown hoards (Stead 1991). As such, it is not impossible that another multi-hoard site, perhaps in the location of a previous hoard find, lies as yet unrecognised. What we can say is that the Iron Age peoples of East Anglia appear to have liked collecting and burying torcs, but that we currently have no evidence that they made them.

Dating overview

The dating of Iron Age gold personal items is fraught with difficulty and art historical dating – according to the presence/absence of certain decorative motifs – has been the norm (for a discussion of the history and issues, see Macdonald 2007). The absence of non-metal finds within hoard contexts has meant that comparative dating is impossible. Conversely, the association of dated coins or other torcs in hoards has often led to assumptions of similar dating for the hoards’ contents, without due consideration that torcs may have been curated/in use for years before their deposition (e.g. Garrow et al. 2009, 103). All these factors have led to a highly confusing, and confused, picture.

There are a few absolute, radiometric, dates (Garrow et al. 2009, 105), however, where these dates have not conformed with the given art historical dating narrative, these dates have been largely ignored. For example, Snettisham L6 torc, gave a secure 790–510 cal. bc. date, but this date was described as ‘impossible to explain’ and was deemed to be ‘unlikely’ (Garrow et al. 2009, 95). Two other copper alloy torcs from Snettisham, dated as part of the same research, gave secure 370–160 cal. bc. dates, but these have been largely bypassed in later literature regarding Snettisham.

In addition, the assumed model of ‘travelling north’ (La Niece et al. 2018, 415) – where torcs are thought to have originated in East Anglia before moving – has created a temporal scenario where anything beyond East Anglia is assumed to be later, derivative. In many ways, this similar model can be seen in relation to continental Europe where torcs from Britain and Ireland have been assumed to be influenced by, and as later variants of, European tradition (La Niece et al. 2018, 411; Stead 1996, 20) which, although this may be true in some cases, has meant that studies of Iron Age art from Britain and Ireland have been seen very much through a European lens. But as Joy states there is ‘no reason why some early developments could not have originated in Britain’ (Joy 2015b, 146) and recent work has suggested that these same gold sheet torcs may not have been made in East Anglia, but instead further north or west (Machling & Williamson 2018, 13).

The source of the gold used to make torcs adds another complication to dating. Iron Age gold is thought to be recycled (Atherton 2016, 47; La Niece et al. 2018, 419). The wide range of gold proportions seen in the broad compositions of these items would appear to support this, with sheet-work and cast torus torc alloys ranging from over 80% gold in sheet-worked examples (e.g. Netherurd and the Great Torc) to below 20% in various cast examples (e.g. North Creake). However, the source of this recycled gold is uncertain and research into the alloy choices of ancient metalworkers with reference to the item being made, which might explain why certain alloys were used, has not been carried out.

Comparable ternary (i.e. gold, silver, copper) alloy proportions are sometimes, though not always, seen in both coins and torcs and this has led to a theory that coins were the alloy source for torcs, which then in turn became an alloy source for coins in the later Iron Age (Gosden 2013, 49; La Niece et al. 2018, 419). This theory is supported by the apparent evidence that coins superseded torcs in the archaeological record in some areas of southern Britain (Hutcheson 2007, 362). However, this theory limits the possible dating for torcs, with current torc dates having to conform to the dates of the earliest c.200BC coins of Britain: the argument runs that if the coins aren’t early, then neither are the torcs. However, the authors believe that the current state of knowledge in Iron Age gold studies does not presently allow for such a definitive answer, for the following reasons:

Firstly, several hoards (for example, Snettisham, Essendon and Netherurd) contain coins and torcs, suggesting that both coins and torcs were equally valued at the time of deposition or alternatively – when considered in the light of other pieces of gold scrap often included in hoards – are evidence of a society where gold was valued and hoarded, perhaps as bullion, no matter what its form.

Secondly, there is no reason to suggest that the early dated torcs – which date prior to the largescale introduction of coins to Britain – and which have been previously assumed to be continental (for example, the Leekfrith, Caistor and Snettisham highly decorated tubular torcs) are not actually early ‘British/Irish’ insular examples. That some torcs look continental, but are in fact insular, is supported by analysis of the Blair Drummond and Irish lobed torcs (Hunter 2018, 434) which show evidence of continental ideas but which were produced from gold alloys and in ways which have distinctively insular signatures.

Thirdly, if the manufacturing dates of some torcs are compared to those of coins, it is clear that several gold torcs could not have been made from imported or ‘British’ coins. For example the Snettisham Grotesque torc, the Caistor torc, the Leekfrith hoard, probably some ribbon torcs and perhaps Clevedon (Machling & Williamson 2019b), appear to have been made around one hundred to two hundred years prior to the large scale introduction of coins to the British Isles (Sills 2017). In addition, the range of ternary alloy percentages present in torcs does not often match those of coins: as such, no clear link to coins can be proved.

Current dating of torcs from Britain and Ireland.

As has previously been stated, the dating of torcs found in Britain and Ireland is confused. Currently, there is a general consensus that, following a hiatus, Plastic style followed the Waldalgesheim/Vegetal style in the 3rd century BC alongside the Sword and Torrs-Witham-Wandworth style (Joy 2015a, 56; Stead 1996, 26) although there is an acceptance that what follows Waldalgesheim is ‘less well understood’ (Fitzpatrick 2007, 341). It is thought that Snettisham style developed from the 2nd century BC (La Niece et al. 2018, 413; Joy 2015a, 41; Stead 1996, 34) although Stead hints that the style ‘developed a life of its own’, perhaps as early as c.200BC (Stead 1996, 34).

Figure d: The Leekfrith, Caistor and Snettisham Grotesque torc and bracelet (Images © The Trustees of The British Museum, The Potteries Museum and The Collection Lincoln)

In terms of individual torcs (Fig. d), Leekfrith and Caistor are deemed to be 400-250BC (La Niece et al. 2018, 411), the Grotesque torc 3rd century BC (Joy 2019, 469) with the Snettisham Great torc and associated ‘bracelet’ 100-50BC (Joy 2015a, 41). The Blair Drummond torcs and the Iron Age quotient of Ribbon torcs (Fig. e) have been given a broader, and less definitive, 300-50BC date range (Hunter 2018, 432). Various other torcs, e.g. Clevedon, Netherurd, Newark, Sedgeford, North Creake, Glascote, Needham Forest etc, have – due to their similarities with Snettisham style material – been given 100-50BC dates also. However, there are no empirical dates for any decorated gold torcs.

Figure e: The Blair Drummond torcs ((Image © National Museums of Scotland)

Thinking beyond art

In light of the above, the authors believe that, as Macdonald states, ‘a fresh analysis of insular material is desirable: one that is deliberately free of the influence of the traditional classification and which accounts for a wider range of aspects and motifs than has been hitherto considered’ (Macdonald 2007, 333).

By looking at technology and manufacturing techniques, in combination with decorative motifs, and by including comparative material both from beyond East Anglia, and within, the authors believe it is possible to suggest that the decorative Snettisham style has its origins in the 4th century BC. Furthermore, we would suggest that it is possible that the origin of the insular Plastic/Torrs-Witham-Wandsworth styles should perhaps be similarly pushed back to seamlessly follow the Waldalgesheim style of the mid to late 4th century BC.

The Snettisham ‘bracelet’

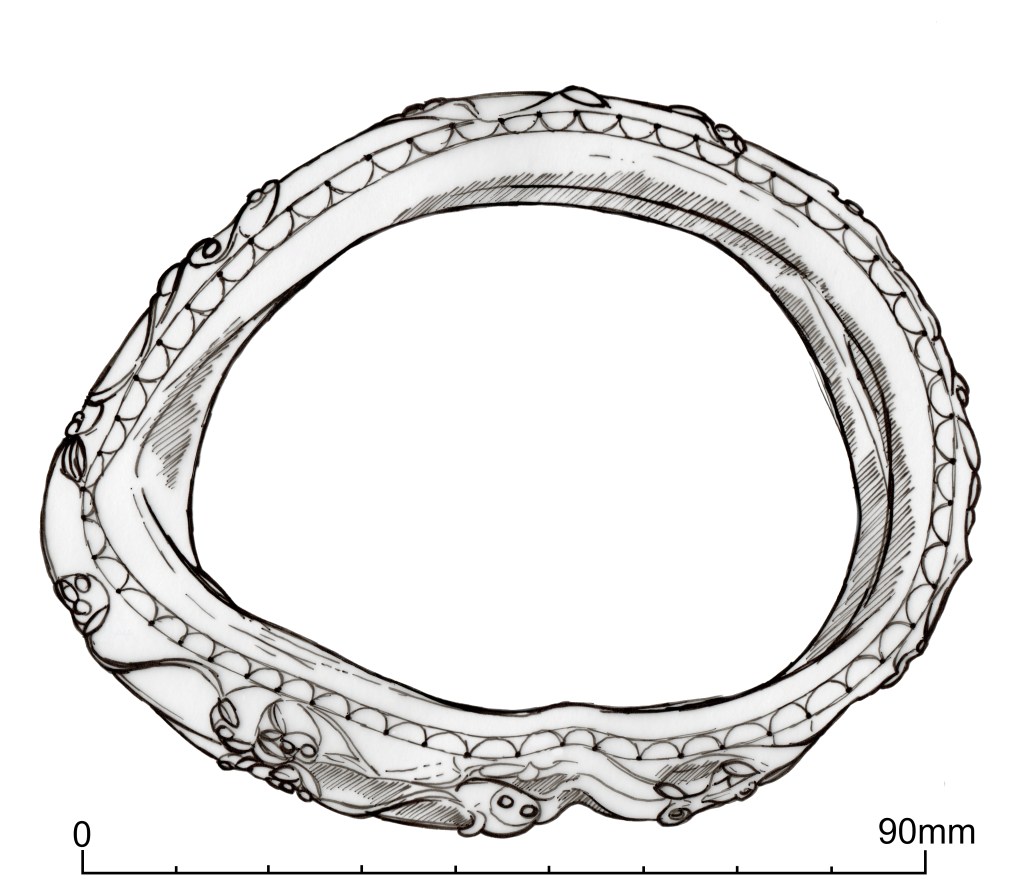

Found attached to the Snettisham Great torc, as part of Hoard E, in 1950, the Snettisham ‘bracelet’ (British Museum catalogue 1951,0402.4) is unique in Iron Age goldwork, both in form and decoration (Fig. 1). Weighing 111g and made from sheet gold, it is of a double-tube formation. It is, however, uncertain whether the ‘bracelet’ was created from two tubes which have been laterally joined, or from a single tube which was compressed along the median. From observation, the latter seems the most probable.

Figure 1: Sketch of the Snettisham arm ring (British Museum catalogue 1951,0402.4). (Image © Roland Williamson & Tess Machling).

The ‘bracelet’ is the only piece of sheet gold that isn’t a torc to be decorated in the Snettisham style, but in contrast to torcs, the decoration is symmetrical about the ‘join’ between the two tubular elements. Jope’s defining hatched tooled panels, dummy rivets and ‘eccentric shapes defined by relief modelling conjured by dome capped trumpets and long curling curved leaves’ (Jope 2000, 84) cover the outer face of the ‘bracelet’ (Fig. f).

Figure f: The Snettisham bracelet (Image © The Trustees of The British Museum)

However, in addition to Jope’s criteria, an extra decorative technique and motif can be seen. Running along both edges of the ‘bracelet’ are parallel lines with recurring semi-circles (Fig. 1, g). Each end of the semi-circle is punctuated with a punched dot. In contrast to lines seen elsewhere on the ‘bracelet’, and on torcs, the parallel lines and semi-circles appear to have been inscribed, rather than punched, and are considerably finer than the punched lines seen elsewhere in the decoration.

Figure g: Close-up of the Snettisham bracelet (Image © The Trustees of The British Museum)

The other aspect of the ‘bracelet’ which has not been previously examined is the diameter: although slightly crushed, an extant section of the ‘bracelet’, and a circumference measurement, suggest an original interior diameter of c.75-80mm, making it much larger than would be typical for a wrist bracelet, where a measurement of up to c.65-70mm would be expected (Swift 2021, 131). The authors would therefore suggest that the Snettisham ‘bracelet’ more likely represents an arm ring.

As has been shown, the Snettisham arm ring is highly unusual both in form and decoration. The authors believe this form and decoration suggest it is a ‘missing link’ between earlier styles, and the full ‘Snettisham Style’ seen in torcs of the period.

Arm rings

Arm rings and closed bracelets are very much indicative of the 4th century Iron Age. Examples of such can be found in the UK from Newnham Croft in Cambridge (Fox 1958, 10) and from further afield in Europe from Waldalgesheim (Joachim 1995, 70) and Erstfeld (Wyss 1975, 35), all of which are securely dated to the mid- 4th century BC. Within the UK, the hoard of Leekfrith, dated to 5th -3rd century BC, contains a bracelet which, although not closed, has tubular form parallels with the bracelets and arm ring from Waldalgesheim (Farley et al. 2018). Like the Snettisham arm ring, the Waldalgesheim twisted tubular arm ring (Fig. h) has an internal diameter of 77-80mm (Joachim 1995, 70).

Figure h: The Waldalgesheim twisted arm ring.

In addition, all the above bracelets, Newnham Croft excepted, are made from hollow gold, like the Snettisham arm ring, with both the Waldalgesheim and Erstfeld bracelet (Fig. i) examples being created from a single tube and, in the case of Leekfrith and the Waldalgesheim arm ring, two tubes.

Figure i: The Erstfeld torcs (Image © The Swiss National Museum)

Decoration

As discussed previously, the combination of incised/engraved fine lines and dots with more standard Snettisham style decoration, is unique. However, three other torc pieces (see below) from Snettisham – again apparently unique in form and decoration, both in Britain and in Europe – show the lines and dots, but this time in association with more standard, Waldalgesheim/Vegetal or Halltstattian geometric-type decoration. In addition, the ‘crown’ from Grave 112 at Deal also shows semi-circles with punched dots (Parfitt 1995, 76), as do the early style daggers from the River Thames at Minster Ditch (Jope 2000, Pl.18) and Hammersmith (Jope 2000, Pl.26).

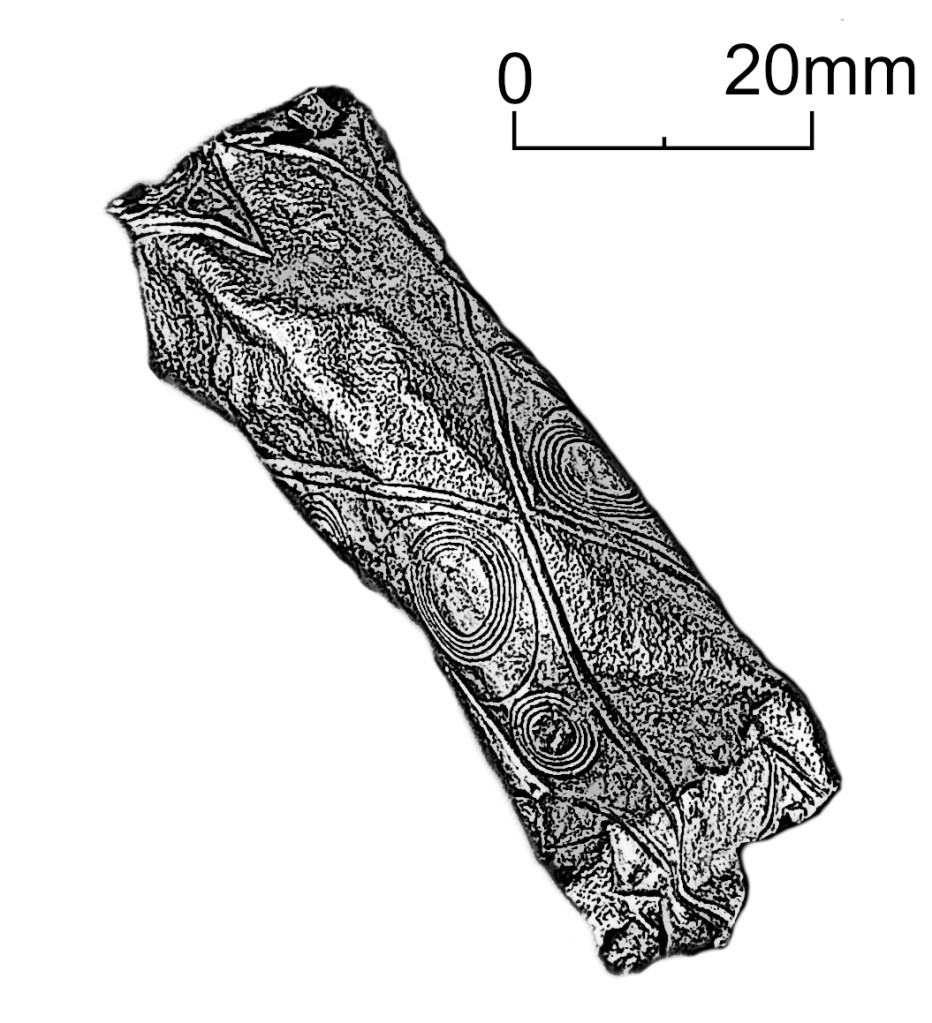

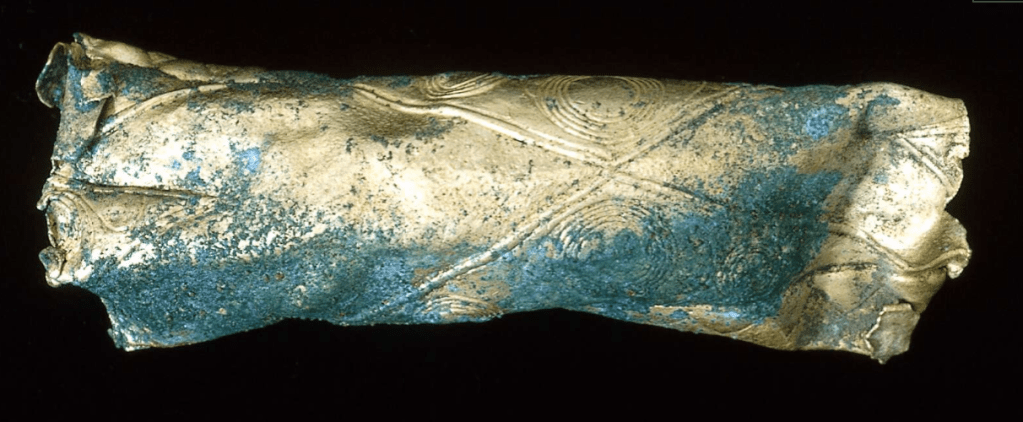

Figure 2: Section of tubular torc from Snettisham (British Museum 1991,0501.118) showing concentric and offset circles. (Image © Roland Williamson & Tess Machling, The Trustees of The British Museum)

A section of tubular torc (British Museum 1991,0501.118) (Fig. 2) and a section of flared tubular torc (British Museum 1991,0501.28) perhaps from the same torc – from Hoard F at Snettisham – and an unstratified torc ‘capped’ terminal (British Museum 1991,0407.40) all show similar semi-circular patterns, with 1991,0501.28 and 1991,0501.118 from Hoard F having slightly more triangular/zigzag lines, and 1991,0407.40 (Fig. 3) showing the same semi-circles as the Snettisham arm ring and Deal crown. All three torc pieces have punched dots at the intersections of each semi-circle/triangle.

Figure 3: The Snettisham capped torc terminal (British Museum catalogue 1991,0407.40) showing semi-circles with punched dots. (Images © Roland Williamson & Tess Machling

In addition, all three of these torc pieces include incised concentric circles and offset concentric circles (Fig. 2) and – with an additional flared torc section from Hoard F (Fig. 4) which shows an offset circle-spiral (British Museum 1991,0501.29) – areas of low relief suggesting that they are very much of a similar date. All four of the torcs from Hoard F mentioned are also decorated in a symmetrical style, often with diamond shapes framing the decoration. Parallels of such off-set circles and lines in semi-circle arrangement can also be seen in the wheel-bow brooch from Newnham Croft (Jope 2000, Pl. 42f&g).

Figure 4: Sketch of the flared tubular torc section from Snettisham (British Museum 1991,0501.29). (Images © Roland Williamson & Tess Machling and The Trustees of The British Museum)

The decoration on the capped terminal shows a typically early (Megaw 2001, 69), human face in relief, with torc 1991,0501.28 and 1991,0501.29 also including ‘subtriangular, curvilinear forms’ (Fox 1958, 147). The offset circle-spirals of 1991,0501.29 also include an arc of raised dummy rivets/dots, reminiscent of those seen on the shield fittings (British Museum 1990,0102.11, 1990,0102.12, 1990,0102.15, 1990,0102.17, 1990,0102.19, etc) and strap fittings (British Museum 1990,0102.26) from Grave 112 from Deal in Kent (Parfitt 1995, 68) and Garton Slack in Yorkshire (Jope 2000, Pl. 264g), on the faces of the Netherurd and Hengistbury Head torcs (Fig. 5) and the collars of the Newark, Sedgeford and South West Norfolk torcs.

Figure 5: Schematic comparison of the Netherurd (top left) and Hengistbury Head (top right) torc terminals, and the strap end (bottom left) and shield fitting (bottom right) from Deal. (Images © Roland Williamson & Tess Machling)

The concentric circles of Snettisham tubular torcs 1991,0501.118, 1991,0407.40 and 1991,0501.28, although rare motifs in the later British Iron Age, are well paralleled in gold torus torcs, appearing in raised form on both the Netherurd terminal and the Snettisham Great torc, in addition to being present on two other gold scraps from Hoard F, with one of the pieces – alongside a scrap of a Plastic decorated torc – being found fused to the flared torc 1991,0501.29 (British Museum 1991,0501.7 & 1991,0501.29). They can also be seen in the newly discovered 5th-4th century BC Maskenfibel from Gloucestershire (Harris 2022).

For Deal, a date from the mid- 4th century to 2nd century BC has been suggested (Parfitt 1995, Sophia Adams pers. comm.) and the British Museum has 400-250BC dates listed on its catalogue for the two Hoard F torcs. This sits well with the Vegetal elements of the flared torcs, which echo those seen on the Newnham Croft bracelet (Fox 1958, 10). The semi-circles and off-set concentric circles seen in the Newnham Croft brooch (Jope 2000, Pl. 42f&g) are also related. In addition, the ‘fan’ seen on the body of flared torc 1991,0501.29 (Fig. 4) can also be seen on the terminals of the 5th-3rd century BC dated Leekfrith double-tube bracelet (Fig. j).

Figure j: Close up of the Leekfrith bracelet showing fan detail (Image © The Potteries Museum)

A further overlap between the Snettisham style and other earlier artefacts, is the triple dot, which can be seen represented on many Snettisham style torcs as a triplicate of punched dots on dummy rivets, for example, on the Snettisham Great torc, the Netherurd terminal and the Newark and Sedgeford torcs. This motif is echoed on the Newnham Croft wheel-bow brooch (Jope 2000, Pl. 42g) but also further afield, for example, on a brooch from Maloměřice in the Czech Republic (Jope 2000, Pl. 42i) or on the triple raised roundels of the Tarn arm ring (Megaw 2001, Pl. 209) (Fig. k).

Figure k: The Tarn arm-ring and close-up of the Netherurd terminal (Images © Megaw & The National Museums of Scotland).

Another aspect of the Snettisham arm ring decoration is its symmetry: the flowing pattern mirrors along the median line (Fig. l). This symmetry is common in 4th -3rd century BC examples (Fitzpatrick 2007, 341) and includes the Plastic style Grotesque (British Museum 1991,0407.37) and mini-Grotesque (British Museum 1991,0501.45) torcs from Snettisham. In addition, Irish scabbards, for example the 4th-3rd century BC Lisnacrogher scabbard (British Museum 1880,0802.115), show a similar mirrored scrolling lyre type pattern (Fig. m).

Figure l: The Snettisham bracelet pattern (After Jope 2000)

Figure m: The Lisnacrogher scabbard (Image © The Trustees of The British Museum).

Dating the Snettisham arm ring

As such, with the double tubular sheet form, symmetry, arm ring diameter and the paralleled semi-circular/triangular lines with punched dots, it does not seem unreasonable to suggest that the Snettisham arm ring is of a possible 4th century BC date.

When the Snettisham style decoration found on both the arm ring and torcs – including the Snettisham Great torc which the arm ring was found attached to – is considered alongside the related forms and decorative arrangements found in torus torcs and on the material from Deal, Newnham Croft, etc, there is no reason to suggest that torus torcs are not also, like Torrs-Witham-Wandsworth in copper alloy, an earlier manifestation of Iron Age goldwork than has been previously assumed, perhaps seamlessly transitioning from Waldalgesheim/Vegetal style to full Snettisham style, via objects such as the Snettisham arm ring.

Technological clues

The manufacturing technology of several torcs adds weight to the above thoughts regarding dating. Recent work on the buffer torc terminal from Clevedon, Somerset (Fig. 6) has shown that it is probable that the current configuration of the terminal results from a later Iron Age cutting down and remodelling of an earlier torus torc (Machling & Williamson 2019b).

Figure 6: Sketch of the probable reworking of the Clevedon torc terminal. (Images © Roland Williamson & Tess Machling)

This would explain the presence of Stage II/I style vegetal scrolls on the terminal body, with Stage V triskele motifs on the face: if the original torus torc that the Clevedon terminal was cut down and remodelled from was of a c.4th century BC torc, then a later reworking would explain both decorative styles being found in the same item. The dimensions of the Clevedon terminal and gold sheet overlaps seen in the terminal support the cut down torus torc interpretation (Machling & Williamson 2019b).

That torcs were reworked and remodelled is also shown by the Netherurd terminal, which was found alone within a hoard, but which had been once attached to a torc and carefully removed from the neck ring prior to deposition (Machling & Williamson 2018, 4). In addition, work on the Snettisham Great torc, has suggested that the Great torc terminals were perhaps not made for the wire neck ring which is currently fitted to them (Machling & Williamson 2019a, 193; 2020b, 90). The recent discovery of the Knaresborough Ring again suggests re-working of torus torcs in later periods.

Similarly, the manufacturing technology of two further torcs from Snettisham – the Grotesque and Great torcs – the Netherurd terminal from Scotland and the Near Stowmarket fragment from Suffolk (Machling & Williamson 2020a) suggest that decorative style may be masking underlying technological similarities, which could perhaps extend to similar dating in all these torcs.

The Grotesque and the Netherurd, Near Stowmarket and Snettisham Great torcs look very different: the Grotesque torc is decorated in high-relief, symmetrical, Plastic style whereas the Snettisham Great torc, the Near Stowmarket fragment and the Netherurd terminal follow the typical conventions of the Snettisham style. However, if the method of manufacture is explored, then all four torcs share a similar technique: the tripartite torus shell, core and collar method (see first image Fig. 6), where an open sheet gold torus shell is sealed with a reel shaped core, before being fitted to a collar and then attached to the wire coiled neck ring (Machling & Williamson 2016, 2018, 2019a, 2020a & 2020b).

However, prior to the authors’ recognition of this construction technique, the dating of the Grotesque torc – according to the art historical approach – sat firmly in the Plastic tradition of the 3rd century BC, with the Great torc, Netherurd terminal and Near Stowmarket piece being 2nd -1st century BC. But on technological grounds, we can perhaps date all four torcs to the same broad period and, with the evidence from the remodelled Clevedon torc and Snettisham arm ring, should now be thinking of dates in the 4th century BC.

A new scheme of torc dates

Webley states that ‘communities either side of the Channel and North Sea shared objects, technologies, ideas and practices throughout the Iron Age, with innovations travelling in both directions’ (Webley 2015, 137) and – with the portable nature of gold working, and probability that such skilled craftspeople travelled (Machling & Williamson 2019a, 185) – it does not seem unreasonable to suggest that innovations in torc design and manufacture were the result of a craft network: a network where goldsmiths – individually or in cohort – innovated, adapted and echoed each other’s work. Decorative styles may have changed, perhaps even contemporaneously, with fashion and region, whilst proven successful technological methods – such as those seen in sheet torus torcs – were often similar.

At present we tend to think that stylistic changes take place over decades, even centuries, but these adaptations and innovations do not need to take time: a single look at a piece of work can result in a new piece created within weeks. One only needs to examine Pytheas’ account – or look at the comings and goings between Gaul, Rome and Britannia recorded by Tacitus – to see that travel across Europe, even in the Iron Age, would have operated in timescales of weeks and months, and not years. As such, innovation, new ideas – and the items made from these ideas – could spread quickly.

It has previously been recognised that the supposed 3rd century BC Torrs-Witham-Wandsworth style is a ‘British version of plastic style’ (Farley & Hunter 2015, 99) and as Jope has noted for the Snettisham style, ‘they are almost all overwhelmingly British and betray little hint of imported influences’ (Jope 2000, 210). Reflections of the style can however, be seen in continental Europe, with Waldalgesheim/Vegetal style and the dotted and raised relief of, for example, the ‘Höhlbuckelring’ from Central and Eastern Europe showing many similarities. But as yet, there is no absolute certainty about which came first.

But, as has been shown, even when the art styles seem similar across Europe – for example, the Blair Drummond and Irish lobed torcs’ similarity to those from south western France (Hunter 2018, 433) – the manufacturing technique and method of production of such sheet gold torcs is very much regionally specific. Conversely, the differing art styles of the Snettisham Great and Grotesque torcs might not necessarily indicate different time periods, when the underlying technology is the same.

From the evidence of the Snettisham arm ring, and other acknowledged 4th century BC material, we would argue that there is enough similarity with what came immediately before to say that Iron Age gold torus torcs of Snettisham style should be re-classified to be yet another insular style following on from, and much influenced by, the 4th century BC Waldalgesheim/Vegetal style. It might even be suggested that – due to the unique form and decoration of the four ornate Snettisham flared tubular torcs – the insular diversification of art in Britain/Ireland occurred perhaps in parallel with Europe at around the same time as the Waldalgesheim/Vegetal style, rather than following it.

Whatever the case, the evidence that the Waldalgesheim/Vegetal style relates to the uniquely insularly styled Snettisham flared tubular torcs, Newnham Croft bracelet, the Leekfrith torcs – and ultimately the Snettisham arm ring – would hint that this insularity commenced in the 4th century BC: much earlier than has been previously assumed. This date sits well with the radiometric dates of the two, albeit copper alloy, torcs from Snettisham dated to the 4th-2nd centuries BC (Garrow et al 2009, 95).

The authors would also suggest that there are enough similarities in technology – and yet no evidence of technological progression – between torcs of the Plastic and Snettisham styles to suggest that Plastic style in Britain and Ireland should be seen as broadly contemporary with, rather than a precursor to, Snettisham style. It could even perhaps be mooted that Snettisham style – with it’s obvious technological and decorative antecedents in Waldalgesheim/Vegetal style, via the Snettisham arm ring – may have its inception before Plastic style in the British Isles. This may also apply to Torrs-Witham-Wandsworth style, which could sit before, or overlap, Plastic style (Ellis-Haken pers. comm.).

Conclusion

The evidence given within this paper, in the light of an absence of alternative secure dating, and thanks to a recognition of faster – and possibly reciprocal – movement of ideas and craftspeople, might suggest that the insular development of Iron Age art and technology within the islands of Britain and Ireland should perhaps be acknowledged to be earlier than has been previously recognised.

As Macdonald states ‘classifications develop a stubborn inertia and hold currency and influence long after the point in time when a sober review of the evidence would discredit them’ (Macdonald 2007, 329). The authors believe that this paper has initiated the ‘sober review’ much needed in Iron Age gold torc studies, and hope that it may in turn inspire a wider re-examination of the art and technology of other Iron Age metal artefacts.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Celtic Gold project for inviting us to speak at the Mainz conference in May 2022, and for the opportunity to produce this paper. We would also like to thank all the wonderful goldsmiths, silversmiths and jewellers who continue to generously share their insight and experience with us: special mention must go to Ford Hallam, Bob Davies and Hamish Bowie whose thoughts inspire so much. We are also grateful to the various curators of the torcs—Sophie Adams, Lucy Creighton, Julia Farley, Glyn Hughes, Fraser Hunter and Tim Pestell—for access to material and stimulating discussion. Ian Stead is thanked for generously sharing his Snettisham notes with us. We would also like to thank those who read this paper, or who discussed the ideas with us, however, all errors and omissions remain our own.

References

Atherton, R. 2016. The Newark Iron Age torc. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire. 120, 43-53

BBC. 2022. Celtic ruler’s ring goes under hammer for £36,000 at auction. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-york-north-yorkshire-63660018

Brailsford, J.W. 1951. The Snettisham Treasure. British Museum Quarterly 16(3), 79–80

Brailsford, J.W. 1971. The Sedgeford Torc. British Museum Quarterly 35(1), 16–19

Brailsford, J.W. and Stapley, J. E. 1972. The Ipswich Torcs. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 38, 219-234

Bushe Fox, J.P. 1915. Excavations at Hengistbury Head, Hampshire in 1911-12. Oxford: Society of Antiquaries of London

Cartwright, C., Meeks, N., Hook, D., Mongiatti, A. & Joy, J. 2012. Organic cores from the Iron Age Snettisham torc hoards: Technological insights revealed by scanning electron microscopy. In C. Cartwright, N. Meeks, D. Hook & A. Mongiatti (eds), Historical Technology, Materials and Conservation, 21–9. London, Archetype.

Clarke, R.R. 1951. A Celtic torc terminal from North Creake, Norfolk. Archaeological Journal 106, 59–61

Clarke, R.R. 1954. The early Iron Age treasure from Snettisham, Norfolk. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 20, 27–86

Clarke, R.R., 1956. ‘The Snettisham treasure’, in Bruce-Mitford, R.L.S. (ed.), Recent Archaeological Excavations in Britain, 21-42

Farley, J & Hunter, F (eds). 2015. Celts: Art and identity. The British Museum & National Museums of Scotland.

Farley J, Gilmore T, Sutherland Z and Nicolls A. 2018. ‘The Leekfrith torcs’ Transactions of the Staffordshire Archaeological and Historical Society 50, 110 – 114.

Feachem, R.W. 1958. The ‘Cairnmuir’ hoard from Netherurd, Peebleshire. Proceedings of the Antiquaries of Scotland 91, 112–116

Fitzpatrick, A.P. 1992. The Snettisham, Norfolk, hoards of Iron Age torques: sacred or profane?. Antiquity, 66, pp 395-398

Fitzpatrick, A. 2007. Dancing with dragons: fantastic animals in the earlier Celtic art of Iron Age Britain. In Haselgrove, C and Moore, T (eds). The Later Iron Age in Britain and beyond. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 339-357

Fox, C. 1958. Pattern and Purpose: A Survey of Early Celtic Art in Britain. Cardiff: The National Museum of Wales.

Garrow, D., Gosden, C., Hill, J.D. and Bronk Ramsey, C. 2009. Dating Celtic Art: a Major Radiocarbon Dating Programme of Iron Age and Early Roman Metalwork in Britain. Archaeological Journal 166:1, 79-123

Gosden, C. 2013. Technologies of Routine and of Enchantment. In Chua, L and Elliott, M (eds) Distributed objects: meaning and mattering after Alfred Gell. Berghahn, New York. 39-57

Harris, J. 2022. South Cerney Brooch. Portable Antiquities Scheme, record number: PAS GLO-9F9843. Available at: https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/1059052

Haselgrove, C. & Moore, T. (eds). 2007. The Later Iron Age in Britain and Beyond. Oxford: Oxbow Books

Hautenauve, H. 1999. Les torques tubulaires de Snettisham. Importation continentale ou production insulaire? Lunala, Archaeologia Protohistorica 7, 89–100.

Hautenauve, H. 2004. Technical and metallurgical aspects of Celtic gold torcs in the British Isles (3rd–1st c. BC). In A. Perea, I. Montero & Ó. García-Vuelta (eds), Tecnología del oro antiguo: Europa y América [Ancient Gold Technology: Europe and America], 119–26. Anejos de Aespa 32. Madrid, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Instituto de Historia, Departamento de Historia Antigua y Arqueología.

Hautenauve, H. 2005. Les Torcs D’Or du Second Âge du Fer en Europe: techniques, typologie et symbolique. Rennes: Association du Travaux du Laboratoire d’Anthropologie de l’Université de Rennes 1

Hawkes, C. F. C. 1936. The Needwood Forest Torc. The British Museum Quarterly 11(1), 3-4

Hawkes, C. F. C. 1940. An Iron Age Torc from Spettisbury Rings, Dorset. The Archaeological Journal 97, 112-114

Hill, J.D. 2004. Sedgeford torc terminal. Portable Antiquities Scheme, record number: PAS-F070D5. Available at: https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/508203

Hill, J.D. 2005. Newark torc. Portable Antiquities Scheme, record number: DENO-4B33B7. Available at: https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/751306 [Accessed: 28/6/22]

Hill, J., Spence, A., Niece, S., & Worrell, S. 2004. The Winchester Hoard: A Find of Unique Iron Age Gold Jewellery from Southern England. The Antiquaries Journal, 84, 1-22.

Hunter, F. 2010. A unique Iron Age gold hoard found near Stirling. PAST: The Newsletter of the Prehistoric Society 65 (July 2010), 3–5

Hunter, F. 2014. Auldearn. Discovery and Excavation in Scotland 15, 97

Hunter, F. 2018. The Blair Drummond (UK) hoard: Regional styles and international connections in the later Iron Age. In Schwab, R; Milcent, P-Y; Armbruster, B & Pernicka, E (eds), Early Iron Age Gold in Celtic Europe: Science, technology and Archaeometry. Proceedings of the International Congress held in Toulouse, France, 11-14 March 2015, 431-440. Rahden: Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH

Hutcheson, N. 2003. Material Culture in the Landscape: A New Approach to the Snettisham Hoards. In Researching the Iron Age, J. Humphrey (eds), 87–97. Leicester Archaeology Monograph 11.

Hutcheson, N. 2004. Later Iron Age Norfolk: Metalwork, Landscape and Society. British Archaeological Reports, British Series 361

Hutcheson, N. 2007. An archaeological investigation of Later Iron Age Norfolk: Analysing hoarding patterns across the landscape. In Haselgrove & Moore 2007 (eds), The Later Iron Age in Britain and Beyond. Oxford: Oxbow Books358-370.

Jacobstahl, P. 1969. Early Celtic Art. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Joachim, H-E. 1995. Waldalgesheim: Das Grab einer keltischen Furstin (Kataloge des Rheinischen Landesmuseums Bonn) Rheinland-Verlag in Kommission bei R. Habelt

Jope, M. 2000. Early Celtic Art in the British Isles. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Joy, J. 2010. Portable Antiquities Scheme, record number: SWYOR-CFE7F7. Available at: https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/392736

Joy, J. 2015a. Approaching Celtic art. In J. Farley & F.Hunter (eds), Celts: Art and identity, 37–51. London: British Museum Press.

Joy, J. 2015b. Connections and separation? Narratives of Iron Age art in Britain and its relationship with the continent. In H. Anderson-Whymark, D. Garrow & F. Sturt (eds), Continental Connections: Exploring cross- Channel relationships from the Mesolithic to the Iron Age, 145–65. Oxford: Oxbow Books

Joy, J. 2016. Hoards as collections: Re-examining the Snettisham Iron Age Hoards from the perspective of collecting practice. World Archaeology 82(2), 239–53

Joy, J. 2018. Snettisham: Shining new light on old treasure. Jewellery History Today 31, 3-5

Joy, J. 2019. A power to intrigue? Exploring the ‘timeless’ qualities of the so-called ‘Grotesque’ Iron Age from Snettisham, Norfolk. Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 38(4), 464–475.

Joy J and Farley J (eds) Forthcoming, The Snettisham Treasure. (London: British Museum Research Publication 225).

La Niece, S; Farley, J; Meeks, N & Joy, J. 2018. Gold in Iron Age Britain. In Schwab, R; Milcent, P-Y; Armbruster, B & Pernicka, E (eds), Early Iron Age Gold in Celtic Europe: Science, technology and Archaeometry. Proceedings of the International Congress held in Toulouse, France, 11-14 March 2015, 407-430. Rahden: Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH

Longworth, I. 1992. Snettisham revisited. International Journal of Cultural Property 1(2), 333–42

Macdonald, P. 2007. Perspectives on insular La Tène art. In Haselgrove & Moore (eds), The Later Iron Age in Britain and Beyond. Oxford: Oxbow 329–38

Machling, T. 2022. Pattern and purpose: a new story about the creation of the Snettisham Great torc. Available: https://bigbookoftorcs.com/2022/05/29/pattern-and-purpose-a-new-story-about-the-creation-of-the-snettisham-great-torc/

Machling, T. & Williamson, R. 2016. The Netherurd torc terminal – insights into torc technology. PAST: The Newsletter of the Prehistoric Society 84 (Autumn 2016), 3–5

Machling, T. & Williamson, R. 2018. ”Up Close and Personal’: The later Iron Age Torcs from Newark, Nottinghamshire and Netherurd, Peeblesshire’. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 84, 387–403.

Machling T & Williamson R. 2019a. ‘”Damn clever metal bashers”’: The thoughts and insights of 21st century goldsmiths, silversmiths and jewellers regarding Iron Age gold torus torcs’ in C. Gosden, H. Chittock, C. Nimura & P. Hommel (eds), Art in the Eurasian Iron Age: Context, connections, and scale. (Oxford)

Machling, T. & Williamson, R. 2019b. ‘”Cut and shuts”: The reworking of Iron Age gold torus torcs’, Later Prehistoric Finds Group Newsletter 13 (Summer 2019), 4-7

Machling, T. & Williamson, R. 2020a. A rediscovered Iron Age torus torc terminal fragment from ‘Near Stowmarket’, Suffolk. Available: https://bigbookoftorcs.com/2020/02/02/near-stowmarket-torc/

Machling, T. & Williamson, R. 2020b. ‘Investigating the manufacturing technology of later Iron Age torus torcs’. Historical Metallurgy. 52, 2 (for 2018), 83-95

Maryon, H. 1944. The Bawsey Torc. The Antiquaries Journal, 24, 149-151

Megaw, J.V.S. 2001. Celtic Art from its Beginnings to the Book of Kells. New York: Thames & Hudson

Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery. 2018. The south-west Norfolk torc. Available at: https://www.artfund.org/supporting-museums/art-weve-helped-buy/artwork/9502/electrum-torc

Owles, E. 1969. The Ipswich gold torcs. Antiquity, 43, 208-212

Owles, E. 1971. The sixth Ipswich torc. Antiquity. 45, 180

Painter, K. S. 1971. An Iron Age gold-alloy torc from Glascote, Tamworth, Staffs. Transactions of the South Staffordshire Archaeological and Historical Society 11, 1969-70, 1-6.

Parfitt, K 1995. Iron Age Burials from Mill Hill, Deal. British Museum Press, London.

Sills, J. 2017. Divided Kingdoms: The Iron Age Gold Coinage of Southern England. Chris Rudd

Stead, I.M. 1991. The Snettisham treasure: Excavations in 1990. Antiquity 65, 447–64

Stead, I. M. 1996. Celtic Art in Britain before the Roman Conquest. 2nd ed. London: British Museum Press

Swift, E. 2021. ‘Bracelets and Torcs’ in A Social Archaeology of Roman and Late Antique Egypt: Artefacts of Everyday Life by Swift, E; Stoner, J & Pudsey, A. Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Webley, L. 2015. Rethinking Iron Age connections across the Channel and North Sea In H. Anderson-Whymark, D. Garrow and F. Sturt (eds) 2015. Continental Connections: Exploring Cross-Channel Relationships from the Mesolithic to the Iron Age, 122-44. Oxford: Oxbow

Whitaker, T.D. 1816. Leodis and Elmete. Leeds: Robinson, Holdsworth & Hurst

Wyss, R. 1975. Der Schatzfund von Erstfeld: frühkeltischer Goldschmuck aus den Zentralalpen. Archäologische Forschungen. Gesellschaft für das Schweizerische Landesmuseum.

11 Replies to “Beyond Snettisham: a reassessment of gold alloy torcs from Iron Age Britain and Ireland.”